Zen And The Art Of Planetary Maintenance

NEWS JUNKIE POST

Jul 19, 2010 at 3:12 pm

When I was first exposed to real Zen practice I was initially struck, and eventually awed at the deep ecological wisdom that is central to life within a Zen monastic community. Not merely taught, but lived.

The supposedly simple act of taking a meal is done in a way that grounds the practitioner in awareness of ecological fundamentals three times a day, every day. I’d like to walk through parts of the Zen practice of oryoki to review those ecological lessons.

The meal begins with a chant done as group in the meal hall, or during monthly sessions of intensive practice, in the Zen hall. The first three lines of one version of the chant is as follows:

First, seventy-two labours brought us this food;

These meal chants are ancient. They date from a time when monasteries grew most of their own food, or at most got it directly from the person who grew it. The “seventy-two labours” did not refer to the clerks and truckers that are now part of our food chain. They referred to the sun, the rain, the insect pollinators, the earthworms, the entire web of living and non-living elements that make up the biosphere.

The “seventy-two” is a metaphoric number simply meant to convey that even a simple bowl of rice requires a vast and complex web of activity before it can be placed in front of us. From the ancient rains that weathered rock into soil up to the stove that heats it, we could not eat without the contribution of every part of that web. In some versions it is “ten thousand”, which is probably closer to the true number.

We should know how it comes to us

How many of us know how our food “comes to us”? It starts with the precarious climate that  permits agriculture and which is under imminent and serious threat (here, here, here, here and here).

permits agriculture and which is under imminent and serious threat (here, here, here, here and here).

It includes the equally complex technological web that means our present Western diet is supported by extensive ocean pollution, wars, chemical refineries, highway systems and packaging industries (to name only a few things). The pesticides and additives that contaminate it. The ethical issues with respect to fair trade, labour issues, and the treatment of animals, etc. All of these are part of every meal, because without them that meal would not be there

In Zen practice these are not things of interest, not something you may want to look into, but rather “We should know how it comes to us”, it is a requirement. For those who don’t know, one place to start would be Food, Inc.: Take someone who doesn’t know. Ways to be more moderate in our impact include eating: locally, organic, becoming wholly or largely vegetarian, buying unpackaged, and including more raw whole foods in our diets.

Second, as we receive this offering we should consider whether our virtue and practice deserve it

Everything must be made from something else. There is no piece of the planet that is not already part of or sustaining the living system in some way. So there is no way to take from it without disrupting that web of life. Everything we consume requires that some part of the natural world be destroyed.

I do not mean simply the killing of a plant or an animal. I refer to all of the destructive activities from mining and logging to farming and transportation right up through to the energy production for your appliances, and the vast infrastructure that is required for each of these elements to function.

Every plastic bag as much as each grain of wheat required that something die. In Zen, we ask ourselves three times a day whether how we live our lives justifies that destruction. What are we giving back that we are more deserving of this use of materials rather then letting the natural world be.

Third, as we desire the natural order of mind to be free from clinging, we must be free from greed

Given the realities discussed above, it is a moral imperative to consume no more than is needed and to not waste anything. This is not merely some empty chanting though. Within true Zen practice it is lived.

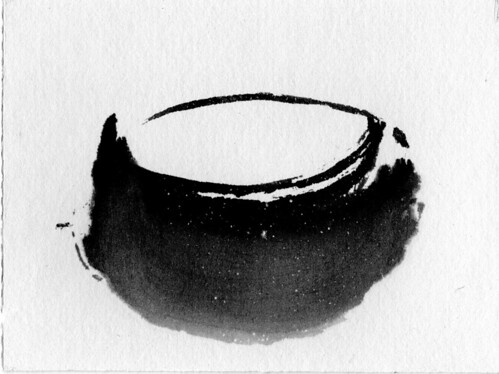

Oryoki meals are taken in three bowls, the largest holding approximately 2 cups, the next slightly smaller, and the third even smaller such that all three can nest together. Generally the first will hold some sort of grain dish, the second a protein dish, and the third a vegetable dish or salad.

Oryoki meals are taken in three bowls, the largest holding approximately 2 cups, the next slightly smaller, and the third even smaller such that all three can nest together. Generally the first will hold some sort of grain dish, the second a protein dish, and the third a vegetable dish or salad.

Of course you can only fill a bowl so full without it spilling the food, so you are constrained from taking too much. There is no second serving. The size of the meal is quite adequate for health and well being, but the way it is taken simply doesn’t allow for greed. In fact the name oryoki translates as “just enough.”

Once the meal is done a large kettle of tea is brought around to clean the bowls. The tea is poured into the bowls which you then clean with a spatula. The tea is drunk along with any remaining tiny scraps of food and then the bowls are wiped with a clean cloth and tied up in a cloth wrapper so that they ready for the next meal.

It is not possible to waste. There is no way to remove food scraps from the hall short of secretly tucking them into your waistband. If you took too much you must eat it anyway, and perhaps take less next time.

Which is not to say that Zen has any monopoly on ecological wisdom. Many volumes are written about the lessons to be found in Christian, Islamic, Judaic, Hindu, Pagan, etc teaching and practice. To the best of my knowledge all preach moderation and gratitude. In all the traditions that I am aware of the most holy individuals are celebrated for their simple lives.

However, it is only in Zen that I have found both the constant reminder of our absolute  dependence on the complex and fragile web of life, coupled with mechanisms that make living that awareness the norm. Therein is the true genius of the oryoki practice. It recognizes that the impulses to greed and waste beset all of us from time to time, and simply makes indulging them impossible.

dependence on the complex and fragile web of life, coupled with mechanisms that make living that awareness the norm. Therein is the true genius of the oryoki practice. It recognizes that the impulses to greed and waste beset all of us from time to time, and simply makes indulging them impossible.

Which begs the question of how we can change the structures of our lives to assist us in making sure that we are free from greed? The oryoki bowls are just right to ensure we have enough without allowing ourselves to over consume on impulse. Are there changes we can make that would do the same for other aspects of our lives ?

How about not carrying debit and credit cards? Leave them at home and take only the cash you will need? or at most a card for an account with a very limited amount of money in it. Or placing garbage cans in very inconvenient places? If every overpackaged item means another trip to the basement or out of doors, it surely get’s us rethinking our waste production.

How about not carrying debit and credit cards? Leave them at home and take only the cash you will need? or at most a card for an account with a very limited amount of money in it. Or placing garbage cans in very inconvenient places? If every overpackaged item means another trip to the basement or out of doors, it surely get’s us rethinking our waste production.

Whatever mechanisms you put in place, be it disposing of your vehicle or shredding your credit cards, the point is to put these things in place when you are thinking about what you want your life to truly be. That is the skillful means of living your convictions, creating the structures and mechanisms to ensure that what you consume is “just enough.” If you leave the decisions to when the impulse is upon you, then there is a very good chance it will play out exactly as it has every time in the past.

There is much more to Zen and art of planetary maintenance, eg

Saving Indra’s net: Buddhist tools for tackling climate change and social inequity

and I will probably be returning to this theme with that lens. The theme being that it is not enough to know and/or care, you have to do. Much more than discipline or good intentions, that art of doing requires self-awareness and skillful means.

Until then, please enjoy this beautiful slide show.

gassho

We give our consent every moment that we do not resist.

Image credits:

Related Articles

- June 7, 2010 Global Solutions: Let’s Play “Grown-Ups.”

- September 14, 2010 Sacred Rites Or Selfish Rights

- August 16, 2010 With Your Fierce Tears: Rage, Rage Against The Dying Of The Light

- April 19, 2010 GIGO: Turning And Turning In The Widening Gyre

- April 26, 2010 Parsing McKibben: If There Be Sorrow

- February 8, 2010 Preaching to the Choir

3 Responses to Zen And The Art Of Planetary Maintenance

You must be logged in to post a comment Login