Human Rights in Turkey: Society’s Moral Obligation to Girls and Boys

The concept of “children at risk” should not only describe those who live on the streets, outside the family order, in an environment with a higher likelihood of criminal activity; this concept should also be expanded to include street children who, driven into criminal activity, are charged and detained in jails where they are again exposed to violence, which these children know only too well.

Here I define “children at risk” as being those who are completely defenseless and immature, are under 18 years old, do not yet have the facility for independent judgment or complex perception and cannot express themselves fully; children who have not yet rescued themselves from traumas experienced at the hands of their families and are forced to protect themselves from violence and sexual abuse, while they try not to starve out on the streets.

That these children are forced to live in this way is nothing less than a humanitarian tragedy. Their rights as children and their rights as humans need to be separately dealt with. Moreover, although the difference in gender must be considered, it should not influence assumptions of guilt. Sexual abuse and violence are not experienced generally by children but differently by girls and boys. The generalization of sexual abuse by conceiving of it as an offense against a child — rather than to a boy or a girl — leads to a misinterpretation of the trauma experienced by the boy or girl. In turn, this results in inappropriate action on behalf of the children by those who wish to help them heal.

When a man sexually abuses a five-year-old girl, she perceives the abuse, when she grows up, as being an attack on her womanhood, and she carries this with her throughout her life. But when a man sexually abuses a five year old boy, the boy doesn’t perceive this as being an attack on his manhood. He grows up to suffer embarrassment for being treated as a woman, and it is this sense of deep shame that he carries with him throughout his life.

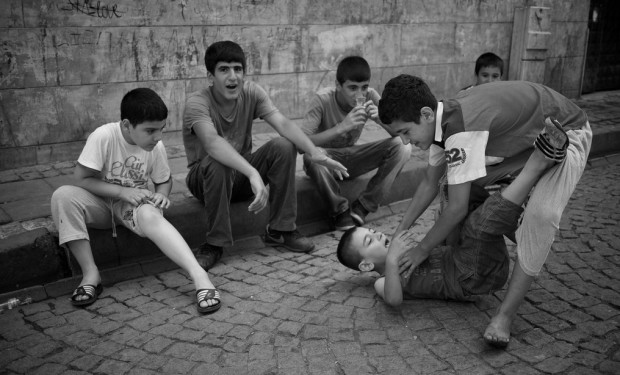

Boys and girls of five or seven or nine or eleven years old become habituated to the violence and sexual abuse perpetrated on them by adults. In turn, many adopt the role of the abuser and perpetrate the same abuse on their peers and on younger children or, at the very least, they fail to stop others from doing so.

The current Turkish justice system determines the concept of crime and punishment for adults and children alike; this system presumes that children can understand the concept of crime and punishment and find the kind of meaning in it that adults can.

But children don’t commit crimes. They make mistakes.

When it comes to punishment, limiting the time that children are allowed to play with their friends or docking their pocket money is usually effective. Behaviors that adults judge as being wrong are often a child’s attempt to protect him or herself, or simply to avoid starvation, in the case of street kids. Street children feel justified in acting the way they do. In addition, such children may not perceive imprisonment as being a punishment, like adults do, because they often wind up alongside their friends, and their hunger is appeased.

When we examine the mindset behind the justice system, we find that street children are considered guilty simply for doing what they must do to survive out there. The next logical step in this system is to detain them. This is an atrocity. Wherever they are, they are just children and children do not need detention. Children are accused of a crime, removed from the circumstances that have caused the so-called crime, and after a period of detention, they are expected to reintegrate into society. Reintegration for a street child might be a well-intentioned goal, but it is palpably idiotic. To label a starving child a thief for stealing bread and ignore the environment in which the crime was committed is nonsense. It is the environment in which the children live that needs improvement.

If the Turkish justice system continues to avoid looking at alleged crimes by children from the children’s viewpoint, the punishment meted out to these children will continue to mean nothing to them. In any case, what children need to be reintegrated into society is not punishment by detention. We do not need to generate a new concept of punishment that children will understand; we need to generate a new concept of what it means to be a child.

Children are just children. From birth, children learn everything they know from the behavior of their mothers and their families, the streets and society. If they commit crime as defined by the justice system, it is not children who are culpable but their families, society and the government. Rather than focus on the ways children commit crime, their families, the society and the government should look to the reality that lies behind their acts. Importantly, a new concept of the condition of childhood should be developed through a consideration and analysis of the consequences of the crimes committed against children on their bodies.

“There are tens of thousands of children out on the streets! We don’t have enough money, we don’t have enough resources. What can we do?”

This is not a question of lack of money or resources. These are excuses that, taken to their logical conclusion, would mean the death of a suicidal society. Where there is money to build sidewalks, where there is money to plant flowers next to roads, where there is money for countless issues with valid grounds, how can children be considered invalid ground and left out of the picture? The answer to this question is not that families, society or government are simply apathetic or mindless of the fate of these children. The answer is that it is to the benefit of society that there are scapegoats, that children who are obliged to live out on the streets are identified as being “the rotten apples in the basket”. Classification of children out on the streets as being crime machines or drug addicts clears society’s conscience and removes any sense of responsibility for these children’s fate. A belief in this classification leaves such children vulnerable to further sexual abuse and violation.

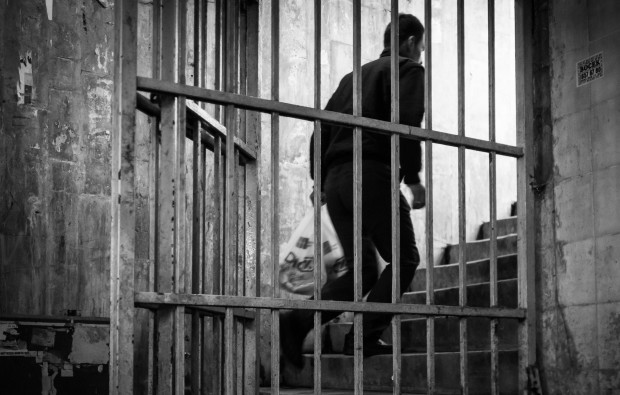

We have seen how putting children into the same category as adult offenders and judging them guilty or innocent allows the Turkish justice system to ignore the desperate condition of children who fall into its clutches. Children are detained pending trial, kept in wards specially reserved for them in jails, and after conviction, sent to juvenile detention centers. Do the police who arrest them, or the prosecutor who hands down a sentence, really have any idea of the hell they are consigning these children to? How can the supposedly mature, responsible adults who follow reports of these children in the newspapers or on the television ignore what is a very real and ongoing tragedy?

- Children as young as five years old have been detained in special wards in jails and sent to juvenile detention centers after being convicted, where they serve out their sentences alongside others up to the age of 18.

- A large majority of children who have been sent to juvenile detention centers manage to escape onto the streets and reoffend, only to be returned to the same jail ward.

- For 80 percent of the children locked in those jail wards, it is their second or third detention.

- Children in those wards are raped by both adult prisoners and other children and/or witness the rapes of younger ones by older ones.

These are the deeply disturbing results of my personal research. Consider the story below, which is one of many.

A boy, let us call him Ali, has run away from home after his parents’ divorce and when his stepfather’s advances became too much for him to handle. He is new to the street. He sneaks into a corner shop and grabs a packet of biscuits. The shopkeeper catches him and beats him, then calls the police who arrest him. Ali is handed on to the prosecutor who considers his case, decides without much preamble that a theft is a theft. After all, theft is against the law, even though the child claims he was hungry. Ali’s case is added to the long list of cases to be heard in court and he’s sent to jail to await his day in court. The shopkeeper, the policeman, the prosecutor, and the judge who will eventually hear Ali’s case under the laws of the land are all family men, all fathers of their own sons.

Ali has no real idea of what he’s done wrong. He took something to eat because he was starving. It was a matter of life and death. Although he doesn’t yet know it, he is now in an even more dangerous place: a jail ward where he will learn what real terror is and where real crimes are committed.

Statistics show that Ali will most likely be raped within his first couple of weeks on the ward. Who has not violated him? The boy on the ward who holds him down, the shop owner, the police, judge or prosecutor?

Even in the Turkish justice system, Ali, who has admitted that he stole the biscuits to appease his hunger, is not considered guilty of the alleged crime until the final verdict is reached. Those arrested on suspicion of a crime are detained in jails under what is called “government protection”. But in those jails, no matter what kind of crime is committed during the night, no matter how loudly the prisoners scream for help, the prosecutor has no mandate to intervene. And were it any concern of his, would anyone wake him and get him up from his bed to come to the jail in the middle of the night for a boy crying rape?

Editor’s Notes: Photographs one, two, four, eight and ten by Thomas Leuthard; three and five by Maria; composite seven by Brett Jordan; and photograph nine by Petr Dosek.

Related Articles

One Response to Human Rights in Turkey: Society’s Moral Obligation to Girls and Boys

You must be logged in to post a comment Login