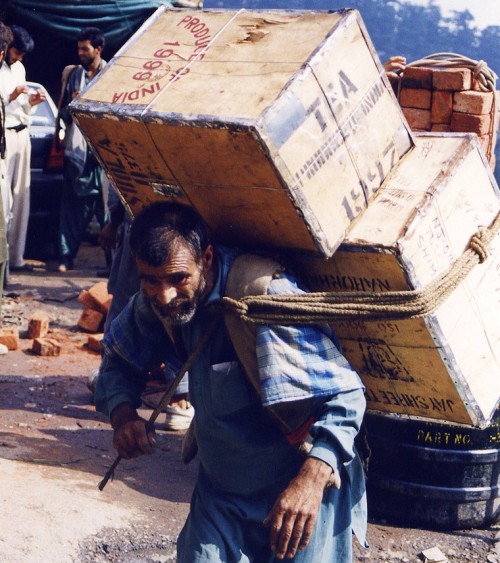

India’s Shameful Class Divide

“If there is no water in the dam…. Should we urinate into it?” – Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister, Ajit Pawar.

In the last few years, India has attracted considerable attention from the world for its “growth story.” India is being celebrated by every single cheerleader of neo-imperialist policy whose sole motive is: profit. Despite this growth, India figures below sub-Saharan Africa when it comes to general undernourishment. “About half of all Indian children are, it appears, chronically undernourished and more than half of all adult women suffer from anemia,” notes Amartya Sen.[1] India is the only country in the world which, despite having the largest unused stock of food, is forced to experience such massive undernourishment. “It is hard to explain it by the presumption of mere insensitivity — it looks more and more like insanity. What could be the perceived rationale of all this?” asks Sen.[2]

The economic policies pursued by right-wing political parties like Congress, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and other regional parties under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have resulted in a massive crisis in India’s agricultural sector, which is considered to be the backbone of the economy. About 87,567 farmers committed suicide in the period between 2001 and 2006 alone. This means that a farmer died every 30 minutes. This does not include women farmers, as most of the land is, by custom, held by men in India. So those who do not formally hold land do not qualify as being farmers. A debt crisis forced most farmers to take their own lives. After the so-called liberalization of the economy, the government-owned seed distribution companies were forced to shut down. The seed price per acre, which in 1991 was about Rs. 70 ($1.25), rose to Rs. 1000 ($17.90): an increase of over 1400 percent.[3]

About one year ago, the Planning Commission, which is headed by Oxbridge’s suave Montek Singh Alluwalia, in an attempt to reduce poverty, brought down the economic indicator that defines poverty. Accordingly, any person in urban India who earned less than Rs. 28.35 (about $0.50) a day would be considered poor. What is this if not an indicator of class assault? Even by the government’s own committee (Arjun Sengupta committee, 2006), over 394.9 million workers (more than 85 percent of the working population and more than 78 percent of the workers in the unorganized sector) live with an income lower than Rs. 20 ($0.36) a day.

India won its independence after a long, tortuous struggle against the British. The famous Karachi resolution (1931) that was passed by the Indian National Congress promised to its citizens a set of rights. These are known as Fundamental Rights under the Indian Constitution. As per the law, any violation of these rights can only be challenged either in a High Court or in the Supreme Court. There are now a total number of 1382 Judges available to enforce these rights, although the population of India has already reached one billion. This might sound ridiculous, but then again it is as hard as a fact from a lawyer (The figures are from the department of law and justice, Government of India’s website.).[4] This means that even these civil liberties in most cases are nothing but paper-tiger promises.

How can one explain this? A vast majority is simply excluded by virtue of being poor; most cannot afford the exorbitant fees of lawyers. Therefore, barring a few super-rich, these rights have no meaning for the vast majority. Most of the states in India live under the shadows of some of the most anti-democratic laws like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) that allows warrantless searches and arrests, and even extra-judicial killings, by the army in areas that are declared to be “disturbed.” One wonders: had Gandhi been alive today what would he have done? Perhaps organize a massive non-cooperation action that would shake the very foundations of this corrupt state.

References

1. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. By Amartya Sen, Penguin Books India, 2012, p. 212 (originally published in 2005 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

2. Ibid, p. 213.

3. P. Sainath http://www.hindu.com/2005/06/30/stories/2005063004691100.htm

4. http://doj.gov.in/?q=node/90

Editor’s Notes: All photographs by Dey.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login