How US Neocolonial Development Failed the Philippines – Part II

The international-dependence theory

“During the 1970s, international-dependence models [of economic development] gained increasing support especially among developing-country intellectuals, as a result of growing disenchantment with both the stages and structural-change models. While this theory to a large degree went out of favor during the 1980s and into the 1990s, versions of it have enjoyed a resurgence in the early years of the twenty-first century, as some of its views have been adopted, albeit in modified form, by theorists and leaders of the anti-globalization movement.” [1] [p.123]

The International-Dependence Theory has seen expressions in three models: (1) the neoclassical dependence model, (2) the false-paradigm model, and (3) the dualistic-development thesis.

The neo-colonial dependence model is basically Marxist in its assumptions. “It attributes the existence and continuance of underdevelopment primarily to the historical evolution of a highly unequal international capitalist system of rich country-poor country relationships.”[p. 124]

In the case of the Philippines’ underdeveloped economy, Jose Ma. Sison, in a lecture at the University of the Philippines (UP) 15 April 15, 1986, titled “Historical Roots of the Philippine Crisis,” documents the following:

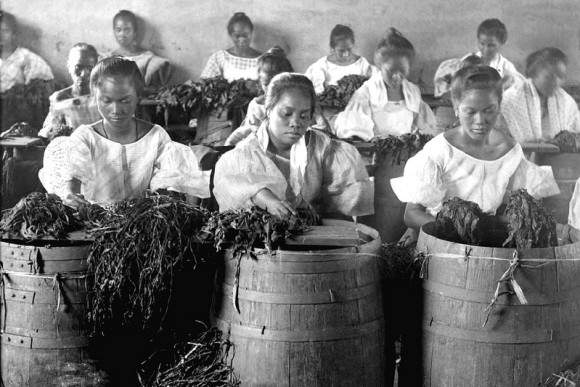

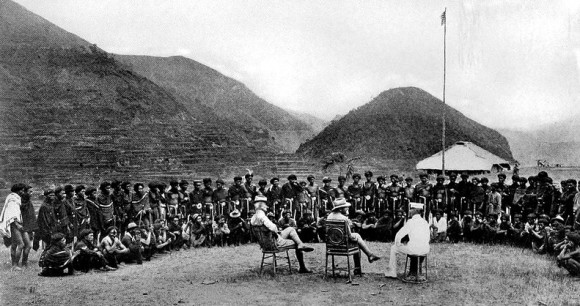

“The defeat of the Philippine revolution resulted in the direct colonial rule of modern imperialism or monopoly capitalism, the highest stage of capitalism, over the Philippines. Capitalism in the US had advanced from the stage of free competition in the 19th century to that of monopoly capitalism in the 20th century.

“Monopolies had become dominant in the American economy. Bank capital, traditionally merchant, had merged with industrial capital. US capitalism was impelled to export not only its surplus commodities but also its surplus capital. In the competition among capitalist powers, the United States was looking after its own monopoly interests. Through monopolies, trusts, syndicates, cartels and the like the United States had moved into a world epoch of intense struggle for colonial and semi-colonial domination. The struggle for a re-division of the world among the colonial powers led to war.”

Todaro and Smith concur thus:

“… [T]he neo-Marxist, neocolonial view of underdevelopment attributes a large part of the developing world’s continuing and worsening poverty to the existence and policies of the industrial capitalist countries of the Northern Hemisphere and their extensions in the form of small but powerful elite or comprador groups in the less developed countries…. Revolutionary struggles or at least major structuring of the world capitalist system are therefore required to free dependent developing nations from the direct and indirect economic control of their developed-world and domestic oppressors.” [p.124]

Again, in the case of the Philippines, Sison further records, by way of another lecture delivered at UP on 22 April 22, 1986 and titled, “Crisis of the Neocolonial State,” the confirmation of what had been said by Todaro and Smith:

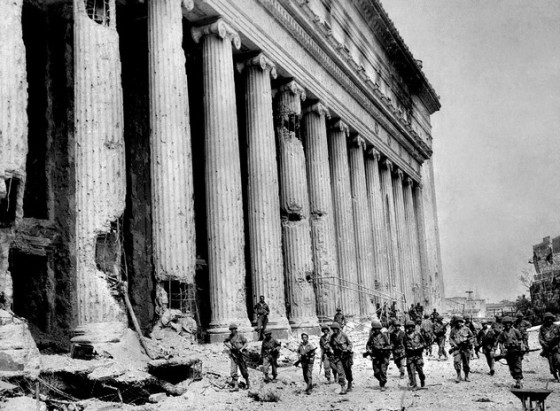

“Under conditions of much-worsened economic crisis, the political crisis of the ruling system also worsens to the point of armed conflict among factions of the ruling classes. The lessening of economic loot for the factions intensifies their political struggle.

“The economic crisis results in widespread social unrest and in the rise of an armed revolutionary movement….”

Getting to the second, false-paradigm, model of the international-dependence theory brings us face to face with “a less radical international-dependence approach to development which… attributes underdevelopment to faulty and inappropriate advice provided by well-meaning but often uninformed biased and ethnocentric international ‘expert’ advisers from developed-country assistance agencies and multinational donor organizations. These experts offer sophisticated concepts, elegant theoretical structures, and complex econometric models of development that often lead to inappropriate or incorrect policies.”[p.125]

Post-war Philippines has seen the proliferation of religion-oriented international NGOs of American Protestant origin, like World Vision, World Relief and World Concern among others. Non-religious entities with the same intention, allegedly to support national socio-economic development efforts, have likewise come in, such that the Philippines has accommodated a myriad of so-called development consultants and advisers to make the country a better place to live in for its local inhabitants. But generally, the country has experienced the reckless implementation of innumerable development programs and projects based on misplaced, inaccurate and groundless advice provided by pseudo-experts coming from developed countries and whose local presence had been enabled by the aforementioned international development organizations operating in the country.

The truth of the matter is that none of these international organizations have genuinely lifted the Philippines from underdevelopment and poverty. In fact, it could be reasonably opined that what these organizations have brought to the country is not true development but exploitation that has pulled it deeper into hardship and poverty. More extreme and radical views even claim that development organizations have been intentionally fielded into the country by agents of US imperialism to perpetuate social, political and economic disempowerment.

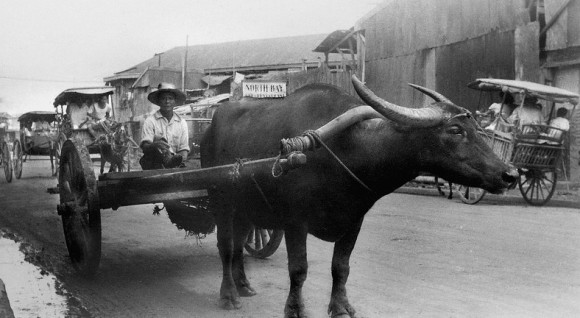

Out of this reality came the dualistic development thesis of the international-dependence theory. Todaro and Smith advance the idea that “[i]mplicit in structural-change theories and explicit in international-dependence theories is the notion of a world of dual societies or rich nations and poor nations and, in the developing countries pockets of wealth within broad areas of poverty. Dualism is a concept widely discussed in development economics. It represents the existence and persistence of increasing divergence between rich and poor nations and rich and poor peoples on various levels.”[p.126]

The neoclassical counterrevolution: market fundamentalism

Neoclassical counterrevolution theory, which purveys market fundamentalism, challenges not only the international-dependence theory but also what it perceives to be an exorbitant government interference with economic activities whose major locus is the market. The theory is carried out through free markets, public choice and market-friendly approaches. Todaro and Smith comment that “it is this very state intervention in economic activity that slows the pace of economic growth. The neoliberals argue that by permitting competitive free markets to flourish, privatizing state-owned enterprises, promoting free trade and export expansion, welcoming investors from developed countries, and eliminating the plethora of government regulations and price distortion in factor, product and financial markets, both economic efficiency and economic growth will be stimulated.”[p.128]

As the neoclassical counterrevolution theory comes out, developing countries like the Philippines are better positioned to realize that the enemy, which is exploitative monopoly capitalism, is concretely found in the free markets, which are not really free at all but controlled and regulated, not by national government, but by the minions and local agents of monopoly capitalism. In this light, the call of neoclassical counterrevolution for freer markets and the dissolution of public ownership, centralized planning and regulated economic activities by government is nothing but a myth meant to deceive, in the context of developing countries where monopoly capitalism can never actually operate unless there is a conspiratorial agreement between foreign investors and the local comprador big bourgeois who are enormously, extensively and excessively supported, represented and promoted by and in the government machineries, both national and local, of a developing country. Hence, the theses and approaches that constitute the neoclassical counterrevolution theory are nothing but bubbles in the air in the circumstances of developing countries. In fact, it could even be inferred at this point that this theory has been advanced as an ultimate attempt to extend the life of monopoly capitalism in its dying moments.

In a developing economy like that of the Philippines, characterized by semi-feudal and semi-colonial conditions, Sison rightly observes that “[t]he comprador big bourgeoisie is the dominant class in the relations of production. It determines the semi-feudal character of the economy. As the chief trading and financial agent of US monopoly capitalism, it lords over the commodity system and decides the system of production and distribution.” Sison further comments that “[u]pon the behest of US monopoly capitalism and in accordance with their own class interest, the comprador big bourgeoisie opposes and prevents the comprehensive industrialization of the Philippines and shares with the landlord class the fear of land reform.”

Let this reflection, though impressionistic in tone and temper, be a reaffirmation of the international-dependence revolution theory as the only genuine expression of a realistic analysis and evaluation of the present conditions and future realizations of developing economies including that of the Philippines.

Reference

1. Michael P. Todaro and Stephen C. Smith, Economic Development (8th Edition), Pearson Education South Asia Pte Ltd., Singapore.

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, five, seven, eight, nine, ten and eleven by Daniel Y Go. Photographs two, three, four, six and twelve from the historical archive of John Tewell.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login