Biodiversity and Sustainability Are Closely Linked to Language and Culture

An unprecedented study of global biological and cultural diversity paints a dire picture of the state of our species.

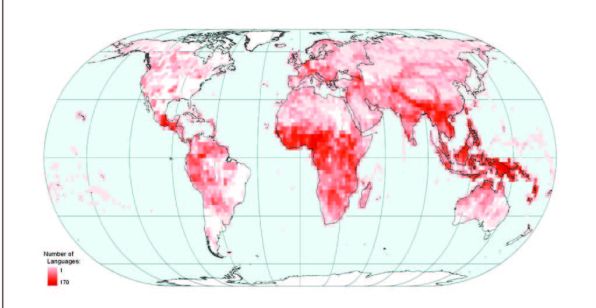

Like the amphibians that climb to ever tinier areas at higher altitudes to avoid being extinguished by global warming, most of the world’s species currently huddle in a tiny fraction of the Earth’s surface, and most human cultural diversity — as measured by the number of languages — occupies essentially the same tiny fraction of the planet.

We are dying.

A scientist would never say it quite this way. Instead, he would tell you that the world’s animal and plant species are disappearing 1,000 times faster than ever in recorded history. He might add that some areas of the world have lost 60 percent of their languages since the mid-1970’s, and 90 percent of the world’s languages are expected to vanish by the year 2099.

In Haitian Creole, we would yell “Anmwe!” (Help!), and this would be right and proper.

As ever, the best scientific studies merely quantify what everybody has known all along. Life, in general, has suffered horribly from the runaway spread of European values and the notions of progress that began with the Industrial Revolution. A sharp bit of mathematics finally brings forth the maps that expose the poverty of the world’s major carbon emitters and the wealth that remains in those parts of the world where the indigenous are making their final stand.

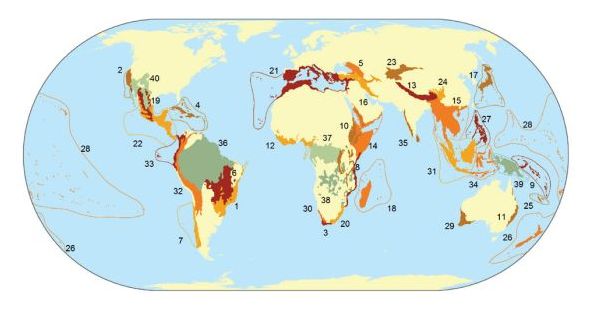

High-biodiversity wilderness areas

There currently exist very few places on Earth that could be considered intact. The researchers found only five such areas, which are numbered 36-40 on the global biodiversity map and colored in shades of green.

These are, by number: 36 = Amazonia; 37 = Congo Forests; 38 = Miombo-Mopane Woodlands and Savannas; 39 = New Guinea; 40 = North-American Deserts.

Together these intact spots amounted to only about six percent of the terrestrial surface but were home to 17 percent of vascular plants and eight percent of vertebrates that could not be found anywhere else. The same areas were the refuge for 1,622 of the world’s 6,900 languages. Little New Guinea topped the chart at 976 tongues.

The only glimmer of hope from the study was the discovery that, contrary to what conservationists might presume, a place does not have to be untouched by humans to serve as a refuge for the world’s plants and animals. Instead, habitats must be handled in the right way, and more than anything, they must be protected from the kinds of blows dealt by industrialization.

Biodiversity hotspots

The researchers additionally identified 35 “biodiversity hotspots,” numbered 1-35 and colored in shades of yellow to red on the global biodiversity map, defined as places with a high density of endemic species despite having lost over 70 percent of the natural habitat.

These were, by number: 1 = Atlantic Forest; 2 = California Floristic Province; 3 = Cape Floristic Region; 4 = Caribbean Islands; 5 = Caucasus; 6 = Cerrado; 7 = Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests; 8 = Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa; 9 = East Melanesian Islands; 10 = Eastern Afromontane; 11 = Forests of East Australia; 12 = Guinean Forests of West Africa; 13 = Himalaya; 14 = Horn of Africa; 15 = Indo-Burma; 16 = Irano-Anatolian; 17 = Japan; 18 = Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands; 19 = Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands; 20 = Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany; 21 = Mediterranean Basin; 22 = Mesoamerica; 23 = Mountains of Central Asia; 24 = Mountains of Southwest China; 25 = New Caledonia; 26 = New Zealand; 27 = Philippines; 28 = Polynesia-Micronesia; 29 = Southwest Australia; 30 = Succulent Karoo; 31 = Sundaland; 32 = Tropical Andes; 33 = Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena; 34 = Wallacea; 35 = Western Ghats and Sri Lanka.

The biodiversity hotspots amounted only to about two percent of the Earth’s surface, but they were home to a whopping 50 percent of plant species and 43 percent of vertebrates that could be found nowhere else. Again, there was a stunning correlation of biodiversity with culture, with the hotspots being home to 3,202 of the world’s languages.

Biodiversity is being lost, but what’s far worse is that the ability to express this loss is vanishing. For example, 1,553 of the languages in hotspots were spoken by only 10,000 or fewer people, and 544 were spoken by fewer than 1,000 people. Ironically, the American researchers who did this study have become regarded as experts on biodiversity, although the only real experts on how to maintain biodiversity in places occupied by humans are the world’s indigenous.

The logical conclusion to take from this study is that modern science, with all its sophisticated technology, is completely trumped by the thousands of years of experimentation by the world’s indigenous, although their findings have been transmitted by oral tradition and other simple means. To be fair, it isn’t so much the fault of modern science as the fault of the industrialized world, which worships power, greed, and the absurdity of exponential growth.

One cannot disdain all other living beings, grind mountains to extract minerals, build roads without a thought for habitat fragmentation, design gardens to please only human aesthetics, or harvest monocultures that serve solely human needs, and expect one’s world to continue for long. There is room for humans at Earth’s banquet, but only those who have lived in place long enough to have learned the contours of their terrain, the language of their plant and animal neighbors and, more than anything, the needs of non humans.

When a shaman leaves a lock of his hair where he has uprooted a medicinal cactus, it is not a bit of imbecility, but a humble acknowledgement that, for each living thing taken, one must give a bit of oneself, however small. For centuries humans have spilled their most beloved animals’ blood to the earth to acknowledge the cyclical aspects of life in preparation for battle and celebration of life’s milestones. These are not concepts that a pharmaceutical corporation could ever understand.

As for every other scientific report, this one concludes that yet more study will be needed, but what is needed, and urgently so, is more humility, because as the world’s indigenous cultures go, so does all humanity.

Editor’s notes. The original article discussed here and images 3 and 5 are in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Images 1 and 6 are of San medicine man Jan van der Westhuizen, by Jan Stuermann. Image 2 is of Haiti’s Solenodon paradoxus, the world’s only venomous mammal, from Arboresciences. Image 4 is of a man in traditional dress in Papua New Guinea, by Bruce Beehler.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login