Haiti’s Creole: Language of Revolution

Theories vary about the genesis of Kreyòl, or Haitian Creole, the most plausible one being that Taino Indians and West Africans, who had evaded slavery together on Haiti’s mountains, probably intermarried and developed a new language. The country’s name itself, Ayiti, is an Arawak word that means mountainous land. The word Vodou, which is essentially synonymous with Haitian culture and religion, originates from Benin and means God — not the God of Christianity, Islam and Judaism created in man’s image, but a polytheistic religion’s most supreme God, wholly indifferent to human affairs, indescribable, and inaccessible except by some manifestations of its aspects in other deities.

Much of Kreyòl’s grammar comes from the African Fon language family, whereas the lexicon represents a mixed bag of African (Fon, Wolof, Kongo, Arabic), Native American (Arawak), and European (Spanish, English, Portuguese).

Haitian proverb: Kreyòl pale, Kreyòl konprann. | Creole spoken, Creole understood. (This is straight talk.)

In the cases of the words borrowed from Europe, historical and cultural changes have altered many of their meanings from the original. For example, the word “Creole” is derived from the Portuguese “crioulo”; its older, more formal meaning, as the category for a person of Portuguese origin who resides in the colonies, has long been lost. Likewise, Kreyòl’s lexicon is replete with French words that have undergone differences in pronunciation, structure, and meaning. For example, the French “ce nègre” (this black man), has changed to “nèg sa” and simply come to mean “this man,” because, you see, in Haiti where we are black, and we have actually fought and won a war against racism, a black person is the definition and reference for human.

How long has Haitian Creole existed? The oldest known text in Kreyòl is a passage from a book by Justin Girod de Chantrans, titled Voyage d’un Suisse dans différentes colonies d’Amérique. It is pure fluff and typical of the soft pornography of colonial times. In a brief two-paragraph section, a slave woman writes about her rape by a man to her lover and swears to him her undying fidelity. The passage is probably a Swiss man’s quite poor rendition of the kind of Creole that was spoken by Haiti’s slaves when the book appeared in 1785.

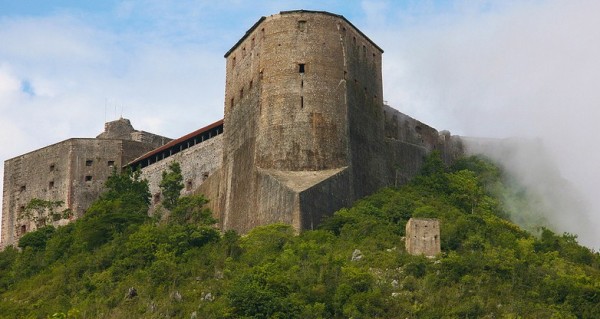

Creole was certainly the tongue spoken at the 1791 Bois Caiman Vodou ceremony that launched the Haitian Revolution. Nevertheless, it was French that served as the text of Haiti’s Independence declaration in 1804 and the only official language of the world’s first black republic for nearly two centuries.

At least two issues prevented Haitian Creole from becoming the country’s official language alongside French. First, Creole was regarded as a bastardization of French and put down as being a patois until 1961, when the work of Félix Morisseau-Leroy and others led to its formal recognition as one of 11 romance languages. Second, the Institut Pédagogique National d’Haiti did not standardize written Kreyòl until 1979.

Proverb: Pale franse pa di lespri pou sa. | French talk does not mean smart.

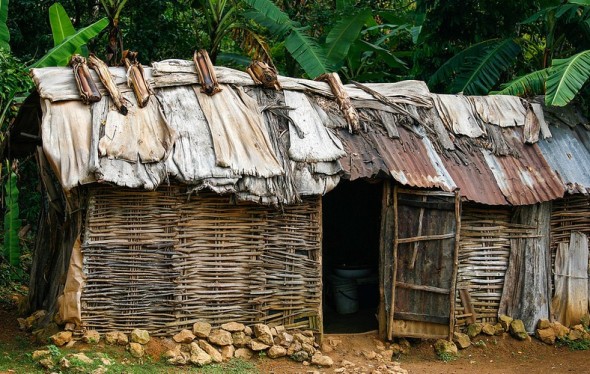

Consequently, for nearly two centuries, a selective use of language excluded the majority of Haitians from all popular debate, in a largely agrarian country where no more than 10 percent had received a formal education or ever spoken French. Only those Haitians who could afford an education spoke French fluently, because all schooling was done in French, and students were forbidden from speaking a word of Creole on their school grounds. Many of these practices continue today. Indeed, for educated Haitians, fluency in French is typically commensurate with the level of schooling, and informal tests of the mastery of conversational French are routinely applied in Haitian society to gauge a person’s wealth and education.

Around 12 million Haitians at home and abroad speak Creole. By contrast, only about one million Haitians speak French. The notion that it is right and proper to address large Haitian audiences in Creole is gradually catching on. This idea started around the 1980s when Haiti’s writers, educators, and journalists began to publish, teach, and inform the population in its native tongue. A milestone in this regard was the 1975 publication of Dezafi, a novel by Haitian writer and playwright Franketienne that is acknowledged as being a masterpiece of literature and is written entirely in Creole. Today Creole is a routine language of Haitian television and radio news broadcasts.

As a language born of revolution, it is fitting that Creole’s official acceptance should have come from the February 1986 rebellion that ousted Jean-Claude Duvalier. Subsequent broad popular discussions produced, alongside a French version, the first major national document in Creole: the 1987 Constitution. In 1991, Kreyòl formally became Haiti’s official language through legislation that had been introduced by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Haitian proverb: Li pale franse! | He is speaking French! (He is obfuscating in French.)

With Aristide’s removal in 2004, much has slowed in the country’s political and cultural evolution. By 2012, the 1987 Constitution had become illegally amended in the French, but not the Creole, version to allow the elimination of popularly elected mayors, municipal judges, Supreme Court justices and their replacement with presidential appointees. These moves have concentrated power in the executive so that it might be better controlled by a coalition of foreign occupiers. In a country where metaphor and reality casually commingle, it is not lost on anyone that there are now two constitutions: one for the rich, another for the poor.

Haitian proverb: Se grès kochon-an ki kwit kochon-an. | It is pig fat that fries the pig. (Greed will undo the rich.)

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, two, and four through ten by Alex Proimos.

Related Articles

18 Responses to Haiti’s Creole: Language of Revolution

You must be logged in to post a comment Login