US Hegemonic Empire and Culture of Death: State Terrorism on a Global Scale

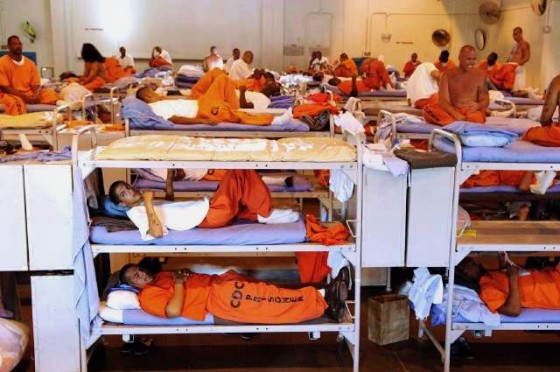

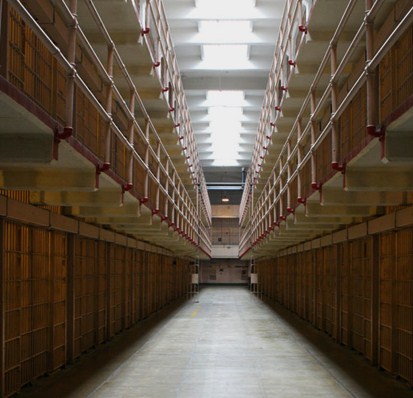

The grand design of the United States global hegemonic empire is founded on an ideological platform of white supremacist domination. “Hegemony,” both in our common understanding and in its specialized Gramscian utilization, is semantically as broad and all-encompassing as “globality,” and therefore “hegemony” is appropriated and assigned the same limitations and specificity. United States global hegemony is effected by the institutionalization of state violence. This brings us to a stark realization of how blatant brutality and ferocious violence still continually dominate a carceral system in the 21st century, putting to shame the “progressive” fantasy of a humanizing modernization and strengthening Bruno Latour’s claim that in reality, “we’ve never been modern” at all, as the shadows of the past continue to haunt us in the concrete embodiment of cultural forms.

Human aggression, displayed in violent attacks against the hated and the dominated, releases the repressed libido of desire with Freudian persistence and the accuracy of Nietzschean eternal recurrence. It is the undying demon of “man’s inhumanity to man” whose echo, from the 1970s movie Papillon, still reverberates and is minted anew in the hegemonic platform of the contemporary US prison system. It is the gates of hell thrown wide open to give way to a tsunami of vicious onslaught against the sacredness of human life in a frenzied orgy that desecrates the body and violates sanity.

In the “Illegalities and Delinquency” chapter of Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault posits that prison has not really failed. “ . . . Prison has succeeded extremely well in producing delinquency, a specific type, a politically or economically less dangerous — and, on occasion, usable — form of illegality; in producing delinquents, in an apparently marginal, but in fact centrally supervised, milieu; in producing the delinquent as a pathologized subject. The success of the prison, in the struggles around the law and illegalities, has been to specify a ‘delinquency.’ . . . So successful has the prison been that, after a century and a half of ‘failures,’ the prison still exists, producing the same results, and there is the greatest reluctance to dispense with it. . . .” (Rabinow, pp. 231-232)

A more focused discussion of American globality creates the poignant impact of contrapuntal narratives that explicate the systematic demolition of the deepest agony of humanity. In other words, we are, in the process, exposed to the massivity of programmed suffering experienced by imprisoned human bodies. What is most clearly perceived, however, is not the biological and corresponding politicization of the biological but a telescoping of the political that abstracts the biological and renders theoretical the entirety of an otherwise passion-challenging moment of relived tragedies. This path of exploratory intent and discovery does not necessarily or automatically lead to concrete action to complete a praxis but most probably leads to further theorizing which, if pursued on a non-dialectical materialist platform, could go on ad infinitum or, worse, ad nauseum.

This totalizing program of global domination is more widely and deeply elaborated by Thomas P. M. Barnett, who talks of a global connectivity that will “trump all, erasing the business cycle, erasing national borders, erasing the very utility of the state in managing a global security order that [seems] more virtual than real.” In this connection, US globality, via its prison regime, is simply the establishment of new rules of massive and deeply-penetrating proportion to manage war and peace in the post-9/11 era, “not just from America’s perspective but from that of the entire world . . . because America is the biggest rule maker in the business of global security affairs.” (Barnett, p. 10). Barnett further contends: “Whether we realize it or not, we are all — right now — standing present at the creation of a new international security order…. The global conflict between the forces of connectedness [American globality in the paper] and disconnectedness [the adversaries of American globality] is here and it is not going away anytime soon. Either America steps up to the challenge of defining this new global security rule set or we will see those rules established by people who dream of a very different tomorrow.” (Barnett, pp. 45-46)

In grave consideration of everything said about American globality, it is extremely important to bear in mind the terrorist design of US imperial hegemony, as its white-supremacist ideology inspires all scorched-earth punitive operations extra-domestically, where this is required. An uncontested place is established for the US as the biggest peddler of global terrorism on the specific basis of an understanding of “terrorism” as being “the contemporary name given to, and the modern permutation of, warfare deliberately waged against civilians with the purpose of destroying their will to support either leaders or policies that the agents of such violence find objectionable.”(Carr, p. 6)

References

Barnett, Thomas P.M. The Pentagon’s New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century. Berkley Books, New York, 2004.

Carr, Caleb. The Lessons of Terror. Random House, New York, 2002.

Rabinow, Paul, ed. The Foucault Reader. PantheonBooks, New York, 1984.

Editor’s Note: Ruel F. Pepa is a retired university academic in the fields of Philosophy and Cultural Studies; he is currently based in Madrid, Spain. All photographs by Publik 15.

Related Articles

8 Responses to US Hegemonic Empire and Culture of Death: State Terrorism on a Global Scale

You must be logged in to post a comment Login