BRICS Bank: A Powerful Challenge to the IMF and the World Bank

Breaking strangleholds of international finance can seem a near impossible task. The provision of finance to developing states, and sometimes developed states humbled by the markets, has tended to be a restricted affair. The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have had their fair share of medicine in that regard.

The Bretton Woods stranglehold has been an enduring one, with fists so clenched they have gone white. Initially, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were designed to keep exchange rates on a stable footing and provide capital for development projects in countries in need of them. In Asia, the same role came to be performed by the Asia Development Bank (ADB). They were intended as the infrastructure doctors, the medical specialists when it came to improving economic health in the developed world.

Subsequently, the scope of their powers changed. Central to their function has been a use of capital that has been deemed coercive, with considerable powers over the budget and economic decisions of recipient countries. The division of rich and poor had translated into a division between those with capital and those bereft of it. The increasing cooperation between powers in the southern hemisphere has also been telling, and this financial reality is not reflected in the traditional Bretton Woods system. The BRICS bank idea, realized at Fortaleza last week, provides a powerful counter.

The genesis of the New Development Bank (NDB) idea in 2009 had a specific purpose: to provide an alternative system to the IMF-World Bank order. World economies were reeling and melting in what proved to be the worst global financial crisis since the Great Depression. The institutional model that has seen the creation of sub-prime mortgages and inventive account keeping on the part of the world’s banks, needed a challenge. The traditional giants, role models of financial conduct, needed a good ticking off.

The underlying tone here is instructive: if you can’t reform the IMF or World Bank, you can at least reform the global lending system by providing soothing alternatives. Its model lies in contrast to the North-South rationale of the Bretton Woods institutions, where the north asserts its traditional dominance over the south. Here, as He Weiwen, senior research fellow at Beijing’s Renmin University explains, the “south-south (hemisphere) cooperation” is vital (Nikkei Asian Review, July 18, 2014).

The south-south emphasis is a crucial operating principle. Brazil, for instance, has more embassies in Africa than the United Kingdom. As a Chatham House briefing paper, Brazil in Africa (2012) explains, “Brazil advocates South-South cooperation projects that are based on its own development experience. Biomedical and health research and agricultural research have been turned into effective foreign policy instruments.”

Much has been made about the idea of a BRICS bank being somewhere between distant dream and hot air. There have also been other fears, traditional ones about another bully muscling in on a playground already filled with cash-heavy bullies. This is particularly acute on the African continent, which has seen all too many examples of infrastructure loans fall foul to control, abuse and diktat.

But from the start of the Fortaleza meeting, powers such as India and China got chatting, with Chinese President Xi Jinping convivial in his discussions with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. As The Economic Times (July 20, 2014) noted, they settled into a room at the Fortaleza Convention Centre, discussing such topics as the Mansovar route for Indian pilgrims, trade and engagement. In the words of the Chinese president, “When India and China meet, the whole world watches.”

The NDB was going to be the tour de force of the meeting, one that reflects almost half of the world’s population, and about one-fifth of the world’s economic production. As a Brazilian diplomat said on condition of anonymity, “The Chinese got the headquarters. The Indians got the first presidency. The South Africans got the regional headquarters. We were happy to facilitate this. And the Russians were happy that finally there is a bank that could challenge the IMF and World Bank.”

Its starting outlay is a cool $50 billion, with each country contributing an equal share. The BRICS countries have also created a $100 billion Contingency Reserve Management (CRA) in the event member countries struggle with balance of payments. Other countries will be able to avail themselves of the NDB’s services. The countries have also thrown in a Business Council arrangement, intended to provide a communicating medium between business leaders and government officials.

There are other potential implications. It is not merely United States influence that is set for a dimming. Tokyo’s financial role may well be weakened as a result of the new bank, given its backing of the Asian Development Bank. The biggest borrowers on the books of the ADB remain China and India. Having the NDB based in Shanghai may well act as a counter to the Japanese regional presence. Beijing, not wanting to stop at this, also intends to create the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). It will need India on board for that to work.

Laudably, the BRICS bank model suggests that countries of strikingly different cultural, religious and historical backgrounds can broker agreements. The common ground, rather, remains shared economic interests and stages of development. What remains to be seen is how far the bank will be able to go when the first customers roll up. Those who are suspicious about the viability of the project, such as the conservative Economist, predict disharmony and internal divisions. It is the differences of the BRICS powers that will divide them, as they “have little in common.” The paper, having proven wrong to begin with, may well be shown up again.

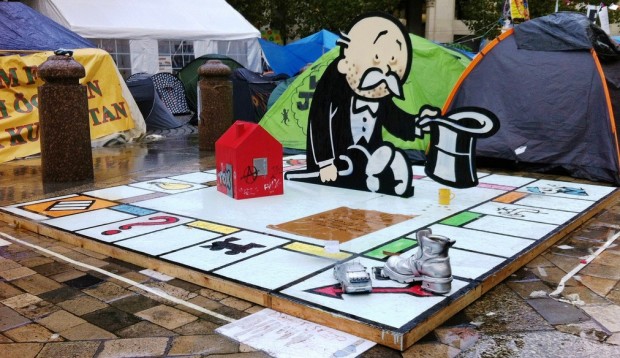

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, three and ten from Government ZA. Photographs two and six by Beth Torr. Photographs four from IMF photo; five by Teacher Dude; seven from Truthout; eight by Scott Montreal; and nine by Michael Thompson.

Related Articles

2 Responses to BRICS Bank: A Powerful Challenge to the IMF and the World Bank

You must be logged in to post a comment Login