PTSD on Memorial Day

NEWS JUNKIE POST

Jun 4, 2012 at 3:51 pm Memorial Day has come and gone for one more year, but our troops remain on the front lines. Remember, it is an all-volunteer force. Only 0.5 percent of the population in the United States serves in our armed forces. I will have more about that number in a moment.

Memorial Day has come and gone for one more year, but our troops remain on the front lines. Remember, it is an all-volunteer force. Only 0.5 percent of the population in the United States serves in our armed forces. I will have more about that number in a moment.

As this most reverent of weekend holidays quickly fades, here are some numbers to take with you as we head into summer. United States dead in Iraq: 4,486. Coalition dead: 312. The official number of wounded Americans in Iraq: 33,184. United States dead in Afghanistan: 1,985 and counting. Coalition dead: 1,034 and counting. Officially wounded in Afghanistan: 16,000 and counting.

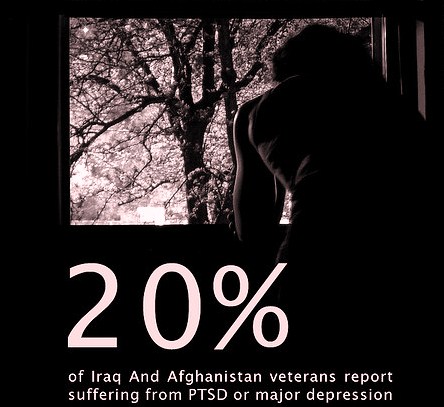

Of all the troops who experienced tours of duty in those two countries, approximately 320,000 have come home with traumatic brain injuries. In 2011, more than 280,000 soldiers received treatment and/or counseling for mental health problems. I fear the number will grow despite America leaving Iraq and starting to wind down in Afghanistan. Approximate is the operative word. We do not know the real number of mental health woes because many veterans refuse to divulge they have a problem. Some only do so when it is too late for proper treatment. The culture of the military still does not make it easy for a soldier to admit he or she has mental problems. Add that the culture of an individual’s upbringing is sometimes similar to that of the military and we have a deeply hidden disorder that will not go away.

Of all the troops who experienced tours of duty in those two countries, approximately 320,000 have come home with traumatic brain injuries. In 2011, more than 280,000 soldiers received treatment and/or counseling for mental health problems. I fear the number will grow despite America leaving Iraq and starting to wind down in Afghanistan. Approximate is the operative word. We do not know the real number of mental health woes because many veterans refuse to divulge they have a problem. Some only do so when it is too late for proper treatment. The culture of the military still does not make it easy for a soldier to admit he or she has mental problems. Add that the culture of an individual’s upbringing is sometimes similar to that of the military and we have a deeply hidden disorder that will not go away.

Mostly, as hard as the military tries, and it was not until recently that the military tried at all, there is a still a culture in the armed services that refuses to acknowledge that soldiers, men and women, suffer from debilitating Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Simply recall how long it took the military to recognize PTSD as a major problem for returning Vietnam veterans. Despite this belated recognition, it will take years to realize the seriousness of PTSD among the troops who returned from Iraq and those still to come from Afghanistan. The disease can take years to develop. Troops return home, some become homeless, some cannot find a job and often what troubles them tears apart once stable families.

Mostly, as hard as the military tries, and it was not until recently that the military tried at all, there is a still a culture in the armed services that refuses to acknowledge that soldiers, men and women, suffer from debilitating Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Simply recall how long it took the military to recognize PTSD as a major problem for returning Vietnam veterans. Despite this belated recognition, it will take years to realize the seriousness of PTSD among the troops who returned from Iraq and those still to come from Afghanistan. The disease can take years to develop. Troops return home, some become homeless, some cannot find a job and often what troubles them tears apart once stable families.

Change might be coming but it appears to me that it is only cosmetic. The recently retired Army Vice Chief f Staff, General Peter Chiarelli, a man deeply concerned about the mental health of everyone in the military, wants to change the name of PTSD to erase the stigma he believes goes with the term Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. He wants to call what some troops suffer Post Traumatic Stress Injury. He hopes that by changing the name from PTSD it will help “reduce the stigma that stops troops from seeking treatment.” General Chiarelli believes that “no 19-year old kid wants to be told he has a disorder.” But not all his efforts have lowered the high suicide rates in the army nor among veterans after leaving the military. There were one hundred sixty-four suicides in 2011. Despite his caring, General Chiarelli still leaves behind a poorly trained staff of behavioral professionals to counsel soldiers in trouble.

Change might be coming but it appears to me that it is only cosmetic. The recently retired Army Vice Chief f Staff, General Peter Chiarelli, a man deeply concerned about the mental health of everyone in the military, wants to change the name of PTSD to erase the stigma he believes goes with the term Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. He wants to call what some troops suffer Post Traumatic Stress Injury. He hopes that by changing the name from PTSD it will help “reduce the stigma that stops troops from seeking treatment.” General Chiarelli believes that “no 19-year old kid wants to be told he has a disorder.” But not all his efforts have lowered the high suicide rates in the army nor among veterans after leaving the military. There were one hundred sixty-four suicides in 2011. Despite his caring, General Chiarelli still leaves behind a poorly trained staff of behavioral professionals to counsel soldiers in trouble.

However anyone parses PTSD, including psychiatrists and psychologists, the entrenched military establishment and the media, for me the definition is still shell shock. No other term applies as clearly. The best writing on shell shock is by British author Pat Barker and her remarkable set of novels, the “Regeneration Trilogy.” Based on the pioneering work of W.H.R. Rivers, a doctor in the First World War, it explores fully and deeply the effect on the mind and psyche of British soldiers who returned home during and after that war. River’s work focused on the “aftermath of trauma, ” that is troops traumatized by battle, that we have no other choice but to read as shell shock. Pat Barker’s books should be required reading for anyone who wants to understand the effects of war on the mind. The lessons of World War 1 still apply. They had and still have meaning for Vietnam veterans and they will continue to help us understand what is happening to the men and women who served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

However anyone parses PTSD, including psychiatrists and psychologists, the entrenched military establishment and the media, for me the definition is still shell shock. No other term applies as clearly. The best writing on shell shock is by British author Pat Barker and her remarkable set of novels, the “Regeneration Trilogy.” Based on the pioneering work of W.H.R. Rivers, a doctor in the First World War, it explores fully and deeply the effect on the mind and psyche of British soldiers who returned home during and after that war. River’s work focused on the “aftermath of trauma, ” that is troops traumatized by battle, that we have no other choice but to read as shell shock. Pat Barker’s books should be required reading for anyone who wants to understand the effects of war on the mind. The lessons of World War 1 still apply. They had and still have meaning for Vietnam veterans and they will continue to help us understand what is happening to the men and women who served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

We must understand that we are dealing with more than 19-year old troopers. PTSD hits people of all ages, whether man or women, whether teen agers or those in their twenties, thirties and older. Psychiatrists who agree with General Chiarelli think, “injury suggests people can heal with treatment.” The theory is that to the afflicted, the word disorder means that something is permanently wrong. There is a possible cure for an injury. Changing PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, to PTSI, Post Traumatic Stress Injury does nothing to change the problem. How we describe something officially does not change its true meaning. I would rather the military was honest about what can badly affect some in the armed forces instead of hiding what it really is behind a set of meaningless words.

We must understand that we are dealing with more than 19-year old troopers. PTSD hits people of all ages, whether man or women, whether teen agers or those in their twenties, thirties and older. Psychiatrists who agree with General Chiarelli think, “injury suggests people can heal with treatment.” The theory is that to the afflicted, the word disorder means that something is permanently wrong. There is a possible cure for an injury. Changing PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, to PTSI, Post Traumatic Stress Injury does nothing to change the problem. How we describe something officially does not change its true meaning. I would rather the military was honest about what can badly affect some in the armed forces instead of hiding what it really is behind a set of meaningless words.

Now, as I promised, I want to return to the 0.5 percent who currently serve in the military. Lest we forget, with Afghanistan in full play, we are now going beyond the longest period of armed conflict that we have ever known in our nation. But fewer and fewer of our population serves because we have the all-volunteer military. To repeat, just 0.5 percent of the American population is on active duty at any one time. The majority of people in America probably do not know anyone in uniform. That means for most Americans there is a serious disconnect between those who fight our wars and those who do not. The only positive element is that unlike during the Vietnam War when returning troops were reviled, the current crop of men and women in uniform are revered, often thought of as heroes because they are doing work that 99.5 percent of Americans are not. When asked, people respond favorably that they understand, and, importantly, appreciate the sacrifice our people in uniform make every day. I am cynical enough to think otherwise. When asked, people prefer to give a positive answer not because they think negatively, but because they do not really think at all about the sacrifice and hardship of those in the military. And part of that sacrifice is often a long-term bout of PTSD.

Now, as I promised, I want to return to the 0.5 percent who currently serve in the military. Lest we forget, with Afghanistan in full play, we are now going beyond the longest period of armed conflict that we have ever known in our nation. But fewer and fewer of our population serves because we have the all-volunteer military. To repeat, just 0.5 percent of the American population is on active duty at any one time. The majority of people in America probably do not know anyone in uniform. That means for most Americans there is a serious disconnect between those who fight our wars and those who do not. The only positive element is that unlike during the Vietnam War when returning troops were reviled, the current crop of men and women in uniform are revered, often thought of as heroes because they are doing work that 99.5 percent of Americans are not. When asked, people respond favorably that they understand, and, importantly, appreciate the sacrifice our people in uniform make every day. I am cynical enough to think otherwise. When asked, people prefer to give a positive answer not because they think negatively, but because they do not really think at all about the sacrifice and hardship of those in the military. And part of that sacrifice is often a long-term bout of PTSD.

How we describe the mental wounds of war will not alter what happens to the person who suffers from PTSD. As much as many do not like it, the United States will be fighting wars of one kind or another for years to come. Men and women will die. Men and women will suffer life-long wounds. Lives will never be the same again. It means we must work diligently to understand and then solve the problems that war brings to those who fight them. If not, we will have a class of permanently mentally debilitated people on the land with little hope of recovery.

How we describe the mental wounds of war will not alter what happens to the person who suffers from PTSD. As much as many do not like it, the United States will be fighting wars of one kind or another for years to come. Men and women will die. Men and women will suffer life-long wounds. Lives will never be the same again. It means we must work diligently to understand and then solve the problems that war brings to those who fight them. If not, we will have a class of permanently mentally debilitated people on the land with little hope of recovery.

Editor’s Note: Photograph number one by Will Lion. Photographs/ composites two, three, four, five, six and seven by Truthout.

Related Articles

- February 26, 2013 Kerry and Hagel: Can Two Vietnam Vets End the War in Afghanistan?

- December 20, 2011 Iraq War: Shame on Us

- May 26, 2013 Memorial Day Patriotism: Cannon Fodder for the Merchants of Death

- June 10, 2010 Obama: Letting Down Veterans With Traumatic Brain Injuries

- August 21, 2010 The So Called “Withdrawal” From Iraq: A Made For TV Drama

- January 26, 2010 1/3rd of Women in US Military Raped

One Response to PTSD on Memorial Day

You must be logged in to post a comment Login