Real Democracy Is Not Part of Global Governance

There has never been a time quite like the present, when the international political system promises so much potential and so much destruction. This system teems with change. Shifts in the centers of power, for example, can profoundly affect global disparity; they can mean the difference between life and death for innumerable human beings. Even the Westphalian system that established the parameters for state sovereignty in the 17th century cannot withstand the transformation of the global political landscape. The changes are affected by technology and international political institutions, which also greatly affect one another. The following evaluation of the concepts of global governance and international order takes into account the dynamics of an ever-shrinking global community and technology’s role in these dynamics.

Today, political overseers transgress against the sovereignty of those inside and outside of their states. Violations of the Westphalian concept of respect for territorial integrity include inter-state conventions, contracts, coercion and imposition. Furthermore, since the end of World War II, global development has driven the changing world order. This predominantly American venture began in the second half of the 20th century, when the United States found itself best able to set the norms of action and enforce them. The US has acted in that capacity for decades. Together with the US’ hegemonic plans for a unipolar system of global governance, technology has played an important role in changing the system post-WWII. It is no secret that nuclear weapons, communication and transportation industries, and energy sources have helped to dictate global affairs for decades. These elements have shaped the outlook on everything, from global economy to collective security and “acceptable cultures” around the world. Technology has become integral to the international political system and global affairs. For example, digital technologies facilitate the global systematization of production, communication and military might. Technology will continue to influence changes in the international political system and the ways in which the major powers attempt to manipulate the international future.

New technologies have shifted the global balance of economic, political, military, and other kinds of power. Political and economic development coincide because political capacity can stimulate economic growth. In least-developed countries (LDCs), greater political oversight can drive economic growth. In other states, however, the fear exists as to whether too much oversight can potentially threaten growth. Nevertheless, higher and more stable levels of oversight can reduce inflation, lower fertility rates, and increase private investment where needed. Many researchers consider that greater political oversight actually stimulates economic development for many middle-income states. This is important because, as the centers of power move, so too will political capabilities. Where power goes, money follows. Undesirable side effects are a real possibility that those middle-income countries will become heavily plagued with disparity, development issues, and a victimization that is often instigated by more powerful totalitarian states and their imperial military and technologies.

Some further argue that weak states also give information about changes in the centers of power, disparity, and distribution. One argument holds that such states help to empower despotic and aggressive governments that can abuse sovereignty, threaten regional stability and, in extreme cases, host war economies. There is also the fear of negative environmental impacts and public health problems. Consider, for example, the disparate responses of the US and Cuba to the Ebola hemorrhagic fever epidemic in West Africa: whereas the US promises military help, Cuba sends medical supplies and doctors to eradicate the problem. These different responses highlight how certain states respond to weak states that pose a challenge to the existing Westphalian system of sovereignty. The existence of such states warrants investigation into their raison d’être. Nation states today, and their inter-subjective connectedness, affect the international political system to an incredible degree. The struggle between domestic rule and the ever-extending state power, all of which occurs within broader international relations, creates oppression and threats.

Historically speaking, despite waxing and waning periods of empire, global governance and international order have been intimately connected. Political episodes have influenced global dynamics within the international political system. Today’s US, for example, recognizes that its short- and long-term economic interests coincide, but it does so only rhetorically. If, for example, the US actually did as much as it could about climate change, renewable energy and clean energy technologies would be part of this dynamic.

With the rise of China as an international political superpower, changes in power politics and international relations seriously fog the already troubled goals on climate change. The US, for one, espouses a system of liberal values that undergird the current global order; it seems incapable or unwilling to engineer a stable climate system. China, despite its potential, has not superseded the US as the world’s leader on climate-change mitigation. Within the international political system today, states are still obviously caught up with one another despite important fluctuations in power. In time, problems reveal their gravity. The fact that a singular power cannot solve a global issue as large as climate change helps to underscore the depth of the current shifts in the international political landscape. Global dynamics continue to metamorphose even as global governance and international order lose all resemblance to their 20th century selves.

Technology has irrevocably altered the international political landscape. Consider the nuclear revolution, for example: this one historic turn has caused a major shift in inter-state political relations. William McNeil and John Herz have noted the significance of gunpowder for the development of the modern European state system. Daniel Headrick has observed the effect of the rifle in the colonial conquest of Africa’s interior and Asian empire; this imperial expansion of 19th century European nation states was a decisive moment for the evolution of an international political system. Benedict Anderson believes that the daily newspaper and its widespread diffusion are inextricably linked to the emergence of nationalism. Today, the tides of digital information technologies are surging. Production, distribution, communication, and other areas grow in tandem with these technologies. They shape the economy and further globalization.

Among the many ways to approach the effect of technology on international politics, an excellent one is to intellectualize the current information revolution as being a social transformation; another is to consider how current information technology influences international politics. To identify technology as being political is important because technology is itself endogenously political—not merely an afterthought. The construction of certain technologies, for example, can stir up political dispute. Technology implies a practical knowledge grounded in material objects as well as the institutions to manage those objects. Technology contributes in deep ways to international politics: it molds political authorities as it changes their efficacy; it alters the domestic and foreign reach of rulers; it informs financial power; it shapes and expands the changing international system’s scope.

States have become more interdependent than ever. To act unilaterally on political matters is no longer the most desirable option, because the effects of a given nation state’s actions are usually too far reaching. Skepticism makes a charitable contribution here: it is important to ask if unilateral actions are actually a new addition to the international political system. Charles Tilly, for example, argues that although European states withdrew from their colonies, the struggles that engendered economically and politically developed European states did not manifest within the former colonies. The external struggles of post-colonial states, and their repression by a world that put legal and normative limits on war, partially explains why not. Again, there was also an enormous shift in power from practically all corners of the globe to the US after the World War II. By the end of the 1940s, the US was contributing virtually half the world’s industrial production, and this allowed it to spearhead many global political, economic, and developmental changes. The US’ post-war development project, however, failed to eliminate poverty, and its liberal world vision lost credibility. Hegemony could not keep its promises of a war-free and poverty-free world.

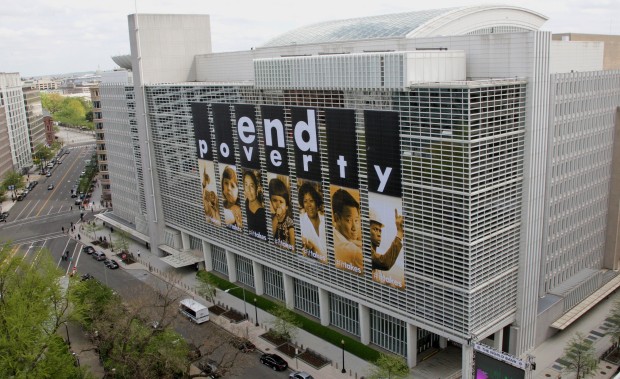

It is worthwhile to ask if billions of people might benefit from a radical restructuring of global governance, and if so, what can states and their treaty-based organizations, offer to this endeavor? Conservative proposals would likely not seek to democratize power on a global scale but, rather, try to prevent violent clashes between the major powers as in World Wars I and II. It is difficult to envisage a global democracy. Many ask whether treaty-based organizations or transnational activist collectives will help to shrink and normalize the current international political system. Issues like transnational civil liberties present formidable hurdles. Some argue that broader and more direct means of participation will prove to be more legitimate than the traditional states’ democratic institutions. Others think that transnational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) will radicalize participation of the marginalized and become key to further democratization. Compared to highly centralized, elitist, and frequently exclusive treaty-based organizations (like the World Bank), activist organizations (like the World Social Forum, WSF) might be a more viable option for the billions of world citizens who typically go unrepresented.

Will only the strong survive the current changes to the international political system? There is little reason to expect that rich and powerful countries will suffer the most harmful effects of something as far-reaching as unchecked climate disaster, especially if technological developments happen in some countries but not in others. Demonstrably, LDCs have suffered, and will continue to suffer, the most deleterious effects of a worsening environment, as many of their ecologies and biological systems have already been depleted or destroyed.

The rich world’s technologies have not done anything noteworthy to assuage the Third World’s paucity of access to such technologies. This has not only cost security and money to the rich world’s economies, but also made them complicit in the deaths of untold numbers of people in the poorer corners of the world. These are not the only harmful effects that have come with changes to the system. Who can know what they all are? Many pressures continue to emerge as the world awaits the full effects of the changes in the international political system. Whether or not the most powerful states in this system will lead the world on solutions to climate change and the current mass extinction event is merely one of many issues.

Editor’s Notes: Photographs: one from US Mission in Geneva archive; seven, eight, nine, ten, and thirteen from the World Bank Photo Collection; two and five by Anjan Chatterjee; four and eleven from the World Economic Forum archive; three from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills archive; six by John Wigham ; and twelve by Let Ideas Compete.

Related Articles

4 Responses to Real Democracy Is Not Part of Global Governance

You must be logged in to post a comment Login