Syria: Could Balkanization Prevent All-Out Sectarian Bloodshed?

Since Syria’s civil war started almost two years ago, it has wrecked the country, displaced more than half a million Syrians to surrounding countries such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, and killed more than 50,000 people (60,000 according to a United Nations estimate). The window has been completely shut for a political solution between the Assad regime and the opposition, which was never seriously pushed by the international community. This diplomatic failure belongs to all parties involved in this proxy civil war, which for many, passes for a “revolution”. On one hand, the West has been unable to recognize that the removal of Assad from Syria will likely put into power Islamists who are aligned with Saudi Arabia; on the other hand, Russia’s has failed to put pressure on Bashar al-Assad to diminish the role of his hardliner brother Maher al-Assad.

While both NATO and Russia are moving military assets into the region, a direct military intervention seems to be excluded as an option. Such an intervention will become even less likely with president Obama’s new nominations for the State Department, the Pentagon and even the CIA, which signal a shift towards a foreign policy more inclined to regard military interventions with greater caution. If Mr. Kerry, Mr. Hagel and Mr. Brennan are confirmed, they should convey to President Obama that putting boots on the ground in Syria would be a grave mistake without a way out. But Mr. Obama has also said that “Assad must go,” and some people in Washington worry that a post-Assad Syria, without a US military presence on the ground, might become like Afghanistan during the rule of the Taliban. Henry Kissinger once tried to capture the forces at play in Syrian politics and history by saying: “Damascus is at one and the same time the fount of modern Arab nationalism and the exhibit of its frustrations. Syrian history alternates achievement with catastrophe.”

This mix of pride and injury is at play again today in Syrian history: the oscillation between a role of being controlled by outside players such as the Ottoman empire or France, and a role of being a player of consequence in the region. But the most pressing problem in Syria — more than the notion that regime change will be a panacea — is the prevention of the all-out sectarian bloodshed that would come with the fall of Bashar al-Assad. In Syria, the sect currently in power are the Alawites, who represent about 11 percent of the overall population. The future of Syria’s 1.2 million Alawites is tied to al-Assad’s regime and completely depends on the outcome of the current civil war.

The Alawite minority has been entrenched in Syria’s power apparatus, both in the public and private sectors, since Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez al-Assad, rose to power in the early 1960s through Syria’s Baath party. In the army and security services, the critical decisions are always made by Alawites. It is difficult for a Sunni to rise to general, and if he does, the second in command in the division is always an Alawite. Even if it is unspoken, sectarianism is widespread in Syrian society. The Syrian army is made up of seven divisions, each one led by a commander. The most important one and the best equipped of Syria’s army is the fourth division, commanded by Maher al-Assad, Bashar’s mercurial brother, with around 45,000 men, all of them Alawites.

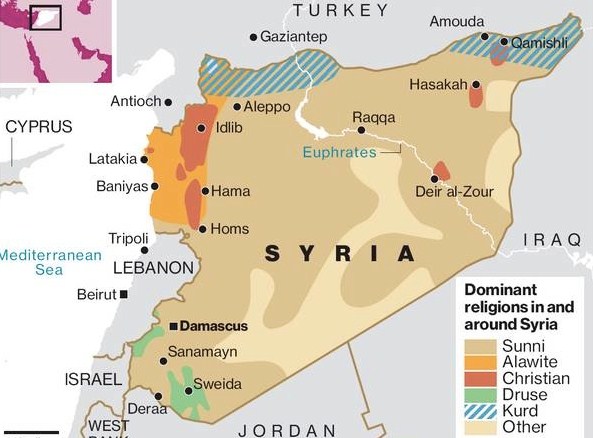

If the Sunni opposition to the Assad regime should get the upper hand in the civil war, the indiscriminate retaliation against Alawites would be extreme. This, in return, would bring new recruits to the already active Alawite militia. The conflict between Sunnis and Alawites is about a thousand years old and is at a boiling point, feeding on the extreme violence perpetrated by both sides. With this incredible amount of “bad blood” between the the two sectarian communities, it is unlikely that they might be prevented from killing each other on a massive scale unless Syria undergoes a Balkanization similar to the one of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Syria’s religious and ethnic groups already have a strong geographic concentration. For example, three quarters of the Allawites live in the Northwestern province of Latakia, where they constitute two thirds of the population. In the context of a Balkanization, Latakia would become strictly Alawite and Christian, two sects who get along well with each other, and autonomous from the Sunni-controlled regions of Syria. In addition, the Kurds who populate the North would also become autonomous. The most difficult decisions would be the fates of Damascus and Aleppo, where all sectarian groups are represented in large numbers. Al-Assad has always made a point of protecting Syria’s sectarian and religious minorities, such as Christians, Druse and Kurd. A partition of Syria would be challenging and have to provide protection and self determination for the communities in question.

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, two, three and four by Douma Revolution. Photograph five by Map by Middle-East Strategy at Harvard.

Related Articles

2 Responses to Syria: Could Balkanization Prevent All-Out Sectarian Bloodshed?

You must be logged in to post a comment Login