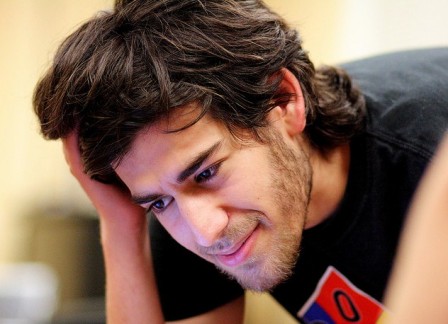

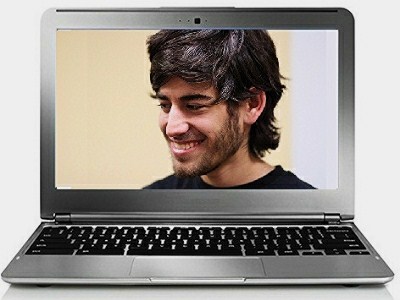

Tribute to Aaron Swartz: Information Guerrilla Warrior

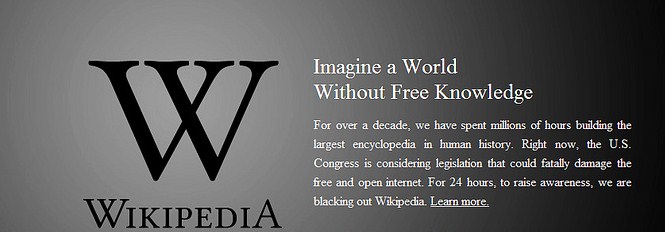

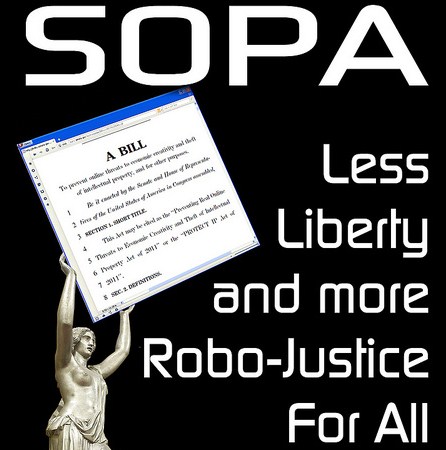

The internet lost a major figure in the person of Aaron Swartz on Friday January 11, 2013. Swartz, who was facing a possible 50 years in prison and $4 million fine for downloading the contents of JSTOR from an MIT computer, hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment. He was 26 years old. Swartz is credited with co-authoring RSS1.0 when he was 14 and being one of the co-founders of Reddit, but his most important contributions to the internet have been his staunch commitment to the free dissemination of information and along with this, the protection of privacy. Swartz was a creator of Tor2Web, a founder of Open Access as well as the Demand Progress movement that successfully fought the Internet censorship bills (SOPA/PIPA). I spoke to Carlos Gomez, who has been involved with the MIT hacker culture since the 1980’s, more specifically about Aaron Swartz and what he stood for.

Dady Chery

Co-Editor in Chief, News Junkie Post

Dady Chery. Aaron Swartz is credited with Tor2Web. Would you explain this contribution? How important is it?

Carlos Gomez. Tor2web is an anonymizer based on a volunteer network. It works as follows. Every request for a web page requires an addressee and a return address, and you need this return address, because the page requested needs to know where to send the information. So how do you get anonymity? Let’s say you are writing a snail mail requesting a document. The upper left corner has the return address; the middle of envelope has the delivery address. You obviously need these two pieces of information. So this envelope goes to a postman who picks it up, the local post office, a central office, etc., and gets passed along many times before it reaches its final destination. Without opening the envelope, anyone who handles it knows where it’s going to and where it came from. Suppose instead, you took the letter, put the “TO” and “FROM” addresses inside it and encrypted the whole thing, and then put that letter in an envelope that had the address of a trusted person instead who knew how to decode it. That person could open the letter, decode the TO and FROM addresses, put it in a new envelope, encrypt it again and forward it. And this could be done any number of times, until the final address is that of the final recipient. Each recipient would only know the previous and next person in the chain. The Tor browser performs the electronic equivalent of this manual encoding/decoding/shuffling of envelopes automatically and transparently for any user of TOR.

DC. How do you know that Tor itself can be trusted?

CG. The TOR software is open-source, meaning that every line of the software is published and open for inspection. While you yourself may not be enough of a geek to verify personally that the software works as intended, you can rely on a large network of highly paranoid geeks who have already minutely examined this code for you. This is in sharp contrast to Internet Explorer or Safari, the default browsers that come preloaded in Windows and Apple computers, respectively. These proprietary browsers are totally black-box, and could be forwarding every syllable directly to the CIA, for all you know. The principles of open source, most eloquently described by Richard Matthew Stallman (rms), are a foundation of free information. People who use software should know its contents and be able to share it and modify it for their personal preference. When you buy a car or anything else, you are entitled to modify it any way you want. You might void the warranty, but you’ll never get arrested.

DC. But if you publish the source, doesn’t this mean that anyone can steal it?

CG. Yes. The same way anyone can plagiarize “To Kill a Mockingbird”. Whoever heard of a work of literature covered under copyright being encoded to keep people from plagiarizing it? It is outrageous that software can be covered by copyright at all. Software is not literature. It is much more like an invention and is more aptly covered by patent law. Of course, patents also require that the principles of any invention be completely explained and accessible. Before patents, inventors used to protect their intellectual property by simply keeping the principles of operation secret. This solution inhibits the growth of engineering knowledge. Patent law is a contract in which the public grants an inventor monopoly rights for a limited term in exchange for a full disclosure of the principles of the invention. Under patent law, every competent individual is ready to exploit the technology as soon as the patent expires, enriching and extending it to the benefit of the general public. It is expected that during the monopoly period, the inventor will be able to recover all of his costs of development plus a reasonable profit. Intellectual property protection of closed-source software tries to have it both ways: they get the protected monopoly, yet the public does not receive the full access to technology that is the public’s side of the bargain.

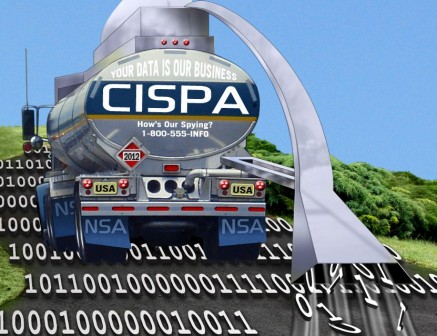

DC. Some say that Swartz’ opposition to SOPA/PIPA made him some very powerful enemies who felt that he was encouraging the theft of their intellectual property.

CG. SOPA/PIPA was meant to protect rights that corporations should not be allowed to have. Copyright laws were developed to protect the livelihood of authors — not the corporations that buy the right to an author’s work. By this reasoning, there is no sense to a copyright outliving its author, since no amount of incentive would entice that author to further efforts. Furthermore, copyrights should be held by real persons, never by corporations, which should have to license the copyright from a living person. The rise of digital media was never envisioned by the original authors of copyright law, and the control of pliant legislators by powerful media conglomerates have led to extensions of copyright law that are totally inconsistent with the original intent of these laws. The only justification that serves the public for a legal protection of “intellectual property” is that this protection ultimately increases, rather than inhibits, access to information.

DC. Aaron Swartz got into legal trouble for downloading JSTOR documents from an MIT computer. What is JSTOR, and do you think this information should be public?

CG. JSTOR is a repository of classic literature from a large variety of fields. This information is typically scanned because it predates digital publishing. Much of this literature is from publicly-funded research. Scientific publications differ from other literature in that they are meant to be applied to future research. In the case of publicly-funded research, taxpayers cannot derive the full benefit of what they have paid for unless they get unfettered access to it. The journals that claim ownership did not pay for the research, did not pay for the authors to write the papers, and did not even pay for the reviews. So their sole, extremely dubious, claim to the ownership of papers is based on their ability to coerce some poor sucker into signing their work over to them for free: the suckers in questions being the authors, the reviewers, and the tax-paying public. Why should we pay to have anybody, including somebody, say, in Ghana, who could not afford the extremely expensive journal fees, be able to get this freely? Science is completely global. It is in the taxpayer’s benefit, not only to have this information available to other taxpayers, but also to have it available to everybody. Another scientist in some unexpected place could be the one who takes the research to the next level. The more eyeballs, the more minds get access, the more robustly science develops. Pure research is founded on the free exchange of information. Anything less than total access means that everyone is being cheated. Period. The taxpaying public, authors and reviewers give up their intellectual property rights specifically so that the information can be made most widely available and applied. Usurpation of these property rights by the journals is theft.

Stallman, who is known for the phrase “Information wants to be free!” carried the concept of free information well beyond software. He invented the concept of “copyleft”, which is a copyright that is taken, not to restrict access to intellectual property but instead to guarantee free access by preempting corporate copyright claims. Swartz’s open access movement basically calls for scientists to take copylefts on their publications rather than surrender their copyright to the journals.

DC. Any thoughts about MIT’s role in Swartz’ troubles?

CG. It is ironic that MIT the institution is so hostile to the ideals of hacker culture, with which many creative people who work for MIT, including Stallman and web creator Sir Tim Berners-Lee, are so closely associated. MIT people have been absolutely instrumental to hacker culture, whose contributions have greatly enhanced MIT’s reputation. Project Athena, for example, which brings academic online courses to the whole world for free is an honor to MIT and a great example of free exchange of information.

DC. What do you think would be a fitting tribute to Aaron Swartz?

CG. Amend the copyright law to say:

1. Any publicly funded research, past or present, is ineligible for copyright protection.

2. Software is not covered under copyright law but properly falls under patent law as an invention.

Read the complete text of Aaron Swartz’ Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto, in his own eloquent words.

Editor’s Note: Photograph one by Sage Ross. Photograph two by Mike Licht and photographs five, six and seven by Donkey Hotey.

Related Articles

3 Responses to Tribute to Aaron Swartz: Information Guerrilla Warrior

You must be logged in to post a comment Login