African Refugees Not Welcome: Xenophobia and Intolerance as Policy

For decades now, the tiny island of Lampedusa, Italy, a little over 100 kilometers from Tunisia and nearly twice that distance from the Italian coast, has been a primary destination for mostly African migrants attempting to reach Europe. With little baggage other than their hopes, these migrants usually brave strong winds, dangerous currents, and hazardous vessels in search of a better chance of survival and perhaps a decent life once in “fortress Europe.”

Many of the people desperate enough to attempt to reach Lampedusa know they have little chance of being granted asylum once they get there. Even after they reach the European Union, securing asylum is no easy task, as they must prove that their lives are endangered in their home nations. Because of this, and also because of their image-building status for the governments that might accept them, political refugees are often given priority. By contrast, socioeconomic refugees are almost always summarily repatriated. They are politically inconvenient.

To reach land alive is in itself uncertain. In the past two decades, refugee migrants attempting to reach European shores have died in the Mediterranean sea at an average rate of over 1,000 per year. In 2011, over 60 migrants were left to die slowly at sea due to an unwillingness of other vessels to rescue them, despite European authorities being made aware of their positions and NATO ships being in the area. Verbal condemnations of the Council of Europe’s catalog of failures and a promise of a drastic change on European migration policies have been quickly forgotten. Perhaps, if they had not, Lampedusa would not have witnessed its most recent catastrophe.

On October 3, 2013, a 20-meter fishing boat with 521 to 545 people, mostly Eritreans, caught on fire off the shore of the tiny Sicilian island. Two commercial fishing vessels received a distress call, but they ignored it and failed to adhere to naval tradition and international law. As the fire propagated through the 20-meter vessel and it began to sink, the boat capsized. The people of Lampedusa took it upon themselves to engage in rescue efforts as best as they could, but 366 people died, including nine children, and about 24 went missing.

European Union policy

The task of reaching Europe has become yet more arduous in recent years for economic refugees. Through supranational institutions and EU mechanisms, countries have found ways to cooperate in patrolling their borders to prevent the free flow of people towards them, as well as to give single states the ability to disavow any responsibility in the matter. Examples include the establishment of: a coordinated radar-detection system to allow supranational police forces to turn back incoming vessels before they reach the territorial waters of states that would be responsible for “processing” the migrants; a European Gendarmerie Force to patrol Europe’s borders; and the expansion of scope, militarization, and power of the already existing Frontex (the EU’s Border Management Agency).

The European Gendarmerie initiative would eliminate the current national bodies of gendarmery (such as the Italian Carabinieri and the Dutch Marachusse) in Europe and re-incorporate them in a supranational paramilitary police force. Not surprisingly the gendarmery forces of the European nations are largely charged with immigration-related duties such as seeking, arresting, processing and deporting “illegal” migrants. Adding insult to the already injurious situation of the migrants who seek asylum or a better life in the European Union, the new police force will have virtual impunity and won’t be prosecutable for any crime or malpractice it commits in the exercise of its activities.

Nobel peace prize for Lampedusa?

Scrutinies and deplorations of the abysmal EU policy have often served to shift responsibility from the culpable nation states to a convenient political scapegoat. “It’s EU policy; it’s out of our hands.” In Italy, for example, the media discourse has not really prompted any serious examination of conscience by the Italian people and government about immigration policies. Indeed, many Italians are under the impression that, far from the tragedy in Lampedusa being the fault of their government, Italy should be praised for being the only nation to have given “illegal” migrants a government funeral. Some Italian members of parliament have proposed to nominate Lampedusa for a Nobel Peace Prize: a move that reeks of self-absolution and whitewashing of the atrocities that migrants are subjected to on a daily basis. There has hardly been any consideration for the living.

Refugees in Lampedusa suffer daily humiliations that could be considered cruel and unusual punishment. A video has surfaced that displays such treatment, with men being ordered to undress publicly and completely in the cold winter air (Yes, Lampedusa can get cold in winter.) and being sprayed with high-pressure water before being left outdoors for a while before their medical examinations. In Italy, such images have had a powerful effect, as they are a reminder of a dark chapter of the nation’s history, when millions of Italians emigrated to the United States and arrived on Ellis Island. Although our treatment was not nearly as demeaning as what the refugees in Lampedusa suffer daily, we were humiliated by the primitive physical examinations intended to discover infectious diseases, and we decried them. It was easier to be outraged when we were the victims.

The situation at Lampedusa is also reminiscent of a verse by one of Italy’s most prominent writers and holocaust survivor, Primo Levi:

“Tell us, you who live safe

In your warm houses,

You who find, returning in the evening,

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider if this is a man

Who works in the mud,

Who does not know peace,

Who fights for a scrap of bread,

Who dies because of a yes or a no.”

Seventy years ago, many could claim to have been ignorant of the existence of the concentration camps and the annihilation of the Jews, homosexuals, and gypsies. By contrast the age of the internet, and widespread knowledge of the abuses in Lampedusa, no longer allows that privilege or excuse. To denude a man publicly is to strip him of a most basic defense and make him feel like cattle. For members of a culture that emphasizes modesty and humility, especially in a public context, the humiliation and shame caused by being publicly denuded is nearly unbearable.

The Italian Center of Identification and Expulsion (CIE – already, the name reveals the lack of intent to consider the refugees as being immigrants, but rather as aliens to be identified and expelled) authorities, who operate the Lampedusa detention center, have justified their actions as being measures to prevent an outbreak of scabies. What has remained largely untold by most of the Italian press, however, is that any possible outbreak of scabies might have resulted from the unsanitary conditions under which the refugees are housed. In particular, the Lampedusa center is intended for a maximum stay of 48 hours, but it has become an overcrowded, dirty and unsanitary long-term detention center that often far exceeds its stated capacity of 381 people. Ironically, the center is officially a “Welcome Center,” where a refugee’s claim to asylum is expected to be assessed within 48 hours.

Bossi-Fini Law

A principal reason for the continued disasters and lack of assistance to boats in need of help, in contravention of maritime law and convention, is the Bossi-Fini law. Bossi is the founder and leader of the infamous and xenophobic Lega Nord party; Fini was a self-declared fascist and admirer of Mussolini (who went on to repudiate fascism later in his career). This legislation not only fails to punish those who do not give succor but also requires the prosecution of anyone who aids an “illegal” migrant in any way, shape or form. Should a boat come to the aid of a sinking boat carrying illegal migrants, the rescue boat would probably be impounded by the Italian authorities. The captain and crew would be subject to prosecution and, if their vessel was eventually released, this would follow a lengthy judicial process.

Italy’s failure to adhere to its international and moral obligations are not an idiosyncrasy of the right. The habit of blaming Berlusconi’s right for Italy’s immigration policies has led to a complete lack of examination of the Italian left’s own responsibility in the tragedies that afflict migrants who attempt to reach the country. In 1997, for example, Romano Prodi’s government was responsible for the deaths of over 80 migrants. In that case, a boat carrying the migrants from Albania was sunk by the Italian military vessel Sibilla as it was engaged in a “maneuver of dissuasion,” i.e. an attempt to stop the boat of migrants from reaching Italian soil.

Various groups of physicians and medical practitioners in Italy have since stated that they will not observe the Bossi-Fini law, as it is incompatible with the Hippocratic oath.

A culture of violence and impunity

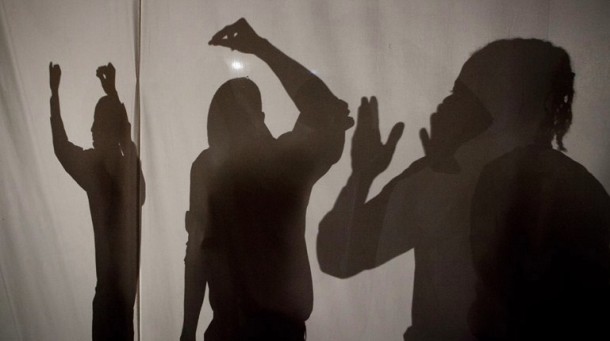

The culture of violence and impunity exemplified in the treatment of migrants and refugees in Europe might be the evident symptom of a system that is rooted in the customs and attitudes of a supremacist ideology. We must take notice that such attitudes are not merely the products of a few bad apples; these are systemic attitudes that have become codified and embedded in the legal system. The result has been that the elements of society that are viewed as being defective, including migrants, women, activists and protesters, are portrayed as being less human or even as being dangerous animals that incubate social and physical diseases and that should be marginalized, expelled, and eliminated. Such portrayal makes it easy to deny entire groups of people their most basic rights and to legitimize the use of excessive and even lethal force against them.

Editor’s Note: Photographs three, four and ten from Active Stills. Photographs one, two, six, eight and nine from Inter Press Agency. Photographs five and seven by Dennis Schulz.

Related Articles

One Response to African Refugees Not Welcome: Xenophobia and Intolerance as Policy

You must be logged in to post a comment Login