College Street, Kolkata: Where Life and Dreams Merge In Books

Books, first and foremost, must disturb, provoke, and yes, unmake me. For me, reading is as important as watching open-blue skies, electric poles with stray crows of afternoon and patches of white clouds that resemble bales of cotton. I suppose I was lucky or smart enough to find College Street while I was young, because it has helped me to find myself, lose myself in myself, find myself in others, and find others in myself. College Street sells dreams yet brims everywhere with little pools of life.

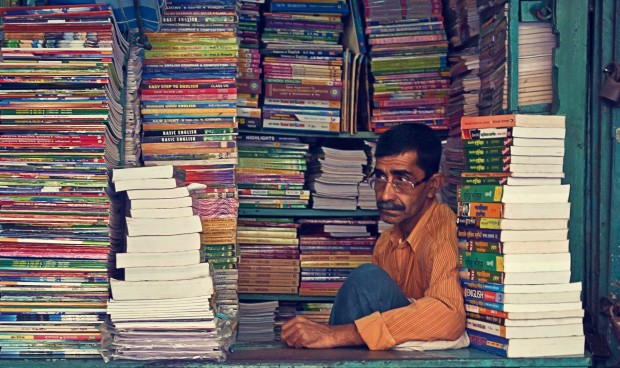

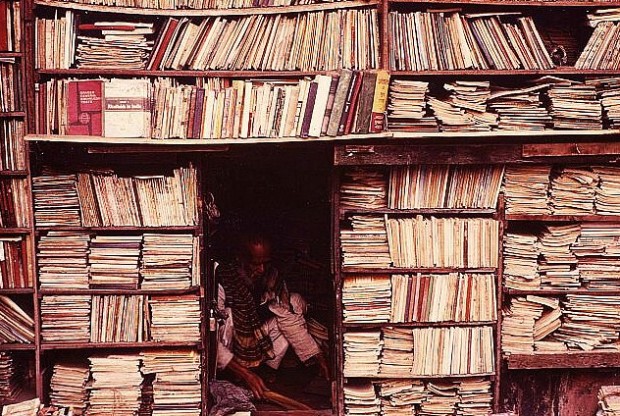

On the right hand corner there, near that old man who sells second-hand books on science, you can find a eunuch looking for a Russian novel published by the now defunct Progress Publishers, Moscow. Here from where I can see her, just to her left, children look through drawing books. Each time they turn the page, they gape with open mouths like ducks. A beggar wearing a coat with patches on his elbows stares at a sky with mushroom-shaped clouds. He scratches his beard and then walks with his head bent as if a thought had dropped from the sky to possess him. He keeps on walking, like a professor who is absorbed by an abstraction yet cares about the world. Everybody is looking for dreams. From one end of the street to the other, one sees the greatest spectacle on earth: books, books and books, waiting to be picked up and taken home. Here in this unique spot, the number of books exceeds the number of people in the ward.

I so enjoy this place called College Street. It is one of the few streets where all one can see is books. A smell of damp pages, dreams, mothballs, chow mein and tobacco hangs in the air. Once in a while, a tram roars by, hisses like a gigantic machine, stops and, with the bell, moves. College Street could justifiably be compared to Kazan of pre-revolutionary Russia. It has a long-standing history of attracting leading revolutionaries. This is not to suggest that the area is free of drug dealers, overtly friendly pimps, and smugglers with the innocent eyes of children. They peacefully cohabit like respectable people. Books have a sobering effect on everyone.

When I tire of being bored, I walk to College Street. I usually prefer the summer. I like to observe the vendors argue over the prices of books with clients and hear their voices melt with the honking of cars and minibuses. One sees many beautiful women in this place. I keep telling myself this is a dreamlike place to fall in love. Imagine this: I go to a shop and see an amazing beauty with curled hair like an Egyptian queen. She settles the locks of her black hair behind her ear to read a book. I see the silhouette of her nose and tips of her curled lips against the golden hues of the evening sun that filters through a glass window. I see myself seeing her. She becomes conscious of my tobacco-flavored breath. She briefly lifts her eyes to meet mine. I feel an upsurge of desire. I feel weak. I say something wise. She is impressed, and that is how we begin our love affair – with forgotten books, golden tea (chai), magical rays of sun, laughter, literary anecdotes, and Marie biscuit. Such things happen only in the life one leads in a novel or fairy tale. I get such ideas probably because I dream a lot of novels, but there is a yawning chasm between the life we dream and the life we live.

I have been coming to College Street for years. As a kid, I came here to sell and buy books. Between me and my mother, I must concede that she is far more intelligent. When I started to visit College Street, she soon noticed that I left home with bags full of books and returned with nothing. Thankfully, she realized that I lacked the merchant’s spirit. I have always been terrible with the things called profit and loss (And what a joy it was to find out, while reading Pablo Neruda’s Memoirs, that the great poet shares this trait!) Since then, I have visited the place to buy books, rip them apart and smell their pages.

Apart from teaching me to distinguish kitsch from art, College Street has taught me how to read my life in books and read books back into my life. Both have become so serious an affair that it is impossible to read books and also live a simple life. It is because of the books themselves that reading is no longer merely reading. I think. I calculate. Living has become like reading. One is always under the apprehension that one is reading what one is living.

I was not yet 16 when I stumbled over Bertrand Russell’s Roads to Freedom. The word freedom, if one understands it correctly, rings in every young heart; mine was no different. I picked up the book and tried hard to read a few pages, but the honking of cars and buzzing of shopkeepers ensured that I read without understanding. I bought the book and thus had my first taste of anarchism – I mean the political theory of anarchism. I cannot, of course, fully recall the book’s content, but I do remember its three lucid and easy-to-grasp essays on Marxism, Socialism and Anarchism. I remember the book’s startling effect on my soul. It awakened in me too many questions.

The book convinced me that, for a fundamental transformation of this rotten slave-based society where one must acquiesce to be a slave or a master, a period of moral cleansing is a must. It also led me to experience a growing sense of isolation. I soon discovered that whenever I spoke or tried to do so with anybody in my class, they accused me of being “utopian.” They knew I was right, but they could not bring themselves to agree with me. I was still in high school but already devoted to books, dreams, books on dreams, and dream-laden books. Slowly, it became evident that by reading such books I was preparing myself for a life-long solitude. Reading, writing and even living are solitary affairs. College Street is the place of my adolescence that asked too many questions.

There was a time when I’d spend the whole day reading books. I was jobless. At evening, I’d wear a warm sweater and stroll through my city. Depending on my whim, I’d take a bus or train, my mind teeming with the characters of a novel that I had just read. I’d observe my black and white city, hear the symphonic cooing of pigeons, study the decaying and time-eaten gothic buildings of Esplanade, the mosques of Central Kolkata chiefly inspired by cartoon boxes; note the exhausted faces of the swarm of office-going men walking in the busy street, returning home with polythene bags. I would calmly continue to walk aimlessly, see liquor shops with grill where men stand in long queues and try to outdo each other by jostling and pushing, see boards nearby with the words “cold beer sold here” and smile at the joke, see skinny boys in shorts sell pirated novels in English at traffic signals near Mahatma Gandhi Road.

I would ask myself questions like: Why did Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina commit suicide? Then I would try to resolve such puzzles with one after another unsatisfactory answer: perhaps because of onto-epistemological failure, perhaps because of a sense of absurdity that haunts most of us, perhaps both Anna and Madame Bovary did not know that consciousness is essentially an unhappy consciousness, as Sartre put it; it is always haunted by a sense of lack. I’d walk the street chewing such thoughts in my mouth as one chews a paan. By late night I would return to my desk and read to forget my solitude.

Editor’s Notes: Imtiaz Akhtar is the author of Kafka Sutra, a collection of short stories. Photographs one, two, four, six, and nine by Steel Monkey. Photographs three, seven and eight by Rishi Bandopadhay. Photograph five by Carl Parkes. Photograph ten by Daniel Roy. Photograph eleven by Rajesh.

Related Articles

One Response to College Street, Kolkata: Where Life and Dreams Merge In Books

You must be logged in to post a comment Login