Nuit Debout: Dawn of a Revolution?

By Gilbert Mercier and Dady Chery

Some call it a phenomenon, others compare it to the failed 2011 Occupy movement, but Nuit Debout has taken the largely discredited French political class, from across the bogus standard left to the far right, by surprise. Sociologically, it should not be a surprise at all. The backdrop is a sense of deep social malaise, a ras le bol et envie de redevenir vivant (a spillover and wish to be alive again). France, as a society, has been morose and depressed for decades, and the state of emergency imposed in a cowardly panicky haste by François Hollande’s administration since November 2015 has turned the country into a pressure cooker.

In the two weeks since it started on the night of March 31, 2016 at the Place de La République in Paris’ XI arrondissement, Nuit Debout has rapidly spread to other cities in France such as Lyon, Nice, Nantes, Toulouse, etc., as well as to Belgium, Germany, and Spain. It could be the remedy for France’s deep social malaise and the sense of being “hankerchiefs to be used and discarded.” An informed observer can see strong similarities with the Situationist, Anarchist and neo-Marxist groups of May 1968, when France’s last mini-revolution toppled its government. Some are already talking of a 6th Republic, which could be either wishful thinking or the dawn of a new revolution.

The French political class is reacting with a mixture of understanding for the protesters and threats of a brutal police crackdown on Nuit Debout’s activists. The Socialist Party, more simply identified in France by its acronym PS, is ironically labeled the Parti Scélerat (Scoundrel Party) by the Nuit Debout activists, in reference to the party’s sell out of all leftist ideals. The Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, personifies the hypocrisy of this ruling party. In a statement to the newspaper Le Monde on April 11, 2016, Mayor Hidalgo did not condemn the movement itself but what she qualified as its excesses: “If it is legitimate to dream of another world, it is not so to degrade this one,” said Hidalgo. She delivered almost immediately on her rhetoric by ordering the evacuation of the Place de la République on the same day. The new and improved French police-state apparatus was eager to execute the order and clear up the square. Elsewhere in Paris, five brutal arrests were made, and people were detained without the proper charges, in accordance with the state of emergency’s extraordinary powers, including arrests without probable cause. The repression has not stopped the momentum of the movement.

Most of the mainstream media in France and elsewhere are drawing an analogy between Nuit Debout and the Occupy movement of late 2011, as well as the Indignados actions in Spain. This is certainly not a coincidence, considering that Occupy largely fizzled and failed for lack of organization and radicalization, just like the Arab spring in the Middle East was hijacked by the West, under United States leadership, to implement regime change policies through fake revolutions in Libya and Syria. The Occupy movement was infiltrated by informants, neutered and more or less dismantled between early December 2011 and late spring 2012 under the instigation of George Soros’ countless little helpers who were paid to hijack the movement. If the Nuit Debout activists follow the tracks of their predecessors of Occupy, the outcome will be the same.

Since 2011, however, throughout the world some elements have greatly changed: the connection between the political class and citizens has reached a breaking point; the notion of elections being a farce has become widespread; wealth concentration and social inequality have reached an unprecedented and unsustainable level; and conflicts and the business of warfare have reached an apex. These factors are fertile ground for the collective quantum leap that is a revolution. As an indication of this shift, a Nuit Debout activist interviewed by the French daily newspaper Liberation said that the movement should consider “a more muscular struggle.”

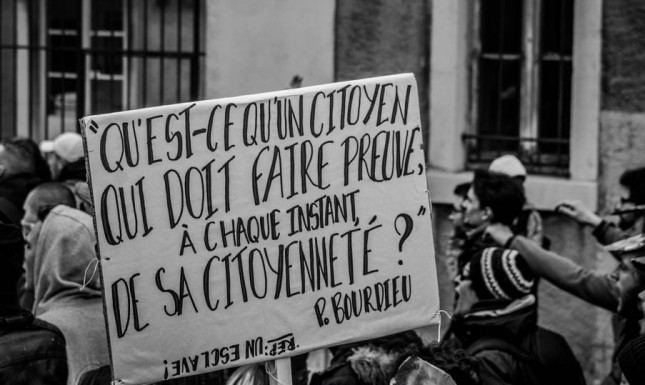

The mainstream analyses do not take into account the fact that France has a revolutionary tradition. The last revolution that bore fruit was in May 1968 and is probably the greatest influence on Nuit Debout. The May 1968 movement started with students and young people, but it quickly expanded to include all the labor unions, which were then very strong. It grew into an open-ended general strike that froze all activities in the country in all sectors of the economy and eventually led to the resignation of President Charles de Gaulle in April 1969 and extensive government reforms. It is May 1968’s humorous and irreverent discourse that we find echoed in Nuit Debout’s slogans today. In 1968, for example, we had “Salaires légers, chars lourds” (Light salaries, heavy tanks), and in 2016 we find “Ils ont les milliards, nous sommes des millions” (They have billions, we are millions). Both movements question the essence of political representation as if all social issues are again up for debate in the public square. Just as in 1968, the labor unions are quickly stepping in and joining the students, and like the activists of the May 1968 movement, the Nuit Debout activists are hunkering down for what they call une lutte prolongée (a prolonged struggled).

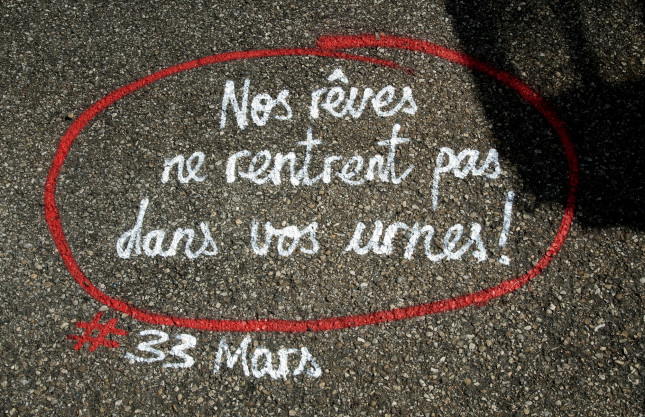

Nuit Debout envisions an era of social justice and ecological responsibility. This is expressed with humor by a suspension of the calendar, as if the month of March will continue until the revolution is achieved. In the Nuit Debout calendar, this article would be published on March 45, and Christmas will fall on March 300. The Nuit Debout movement exudes a contagious joy, which is a necessary ingredient in the cocktail of every successful revolution. A revolution, after all, must be departure from the status quo. Today’s revolution must displace the suicidal worship of wealth and power to create a joyous culture that is sustainable and celebrates life. The richness of the burgeoning discourse, and the inclusion of cultural elements like cinema and song are good omens for the success of Nuit Debout. On a fine day in March we might again hear an old classic from 1789: “Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira! Les aristocrates à la lanterne….”

Editor’s Notes: Gilbert Mercier is the author of The Orwellian Empire, and Dady Chery is the author of We Have Dared to Be Free. Photographs one and three by Nicolas Vigier; two and five by Titi Photo; six by Georges; and eight by Thierry Ehrmann.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login