EGF: Europe’s Multinational Militarized Police

Far from the prying eyes of the European public, in the small town of Velsen in the Netherlands, in October 2007, the ministers of Foreign Affairs and of the Interiors of five EU nations signed the first treaty to establish a supranational and multinational military body of the European Union: the European Gendarmerie Force (EUROGENDFOR or EGF). The Treaty of Velsen was intended to form a “multinational police force with military status… which shall be operational, pre-organised, robust, and rapidly deployable, exclusively comprising elements of police forces with military status of the Parties, in order to perform all police tasks within the scope of crisis management operations.” EGF was founded as a complementary component, and under the direct auspices, of NATO and the UN peacekeeping forces. Indeed, the original treaty explicitly acknowledges considerations of “the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington on 4 April 1949… the Charter of the United Nations signed at San Francisco on 26 June 1945… [and] the Agreement between the Parties to the North Atlantic Treaty regarding the Status of their Forces, signed in London on 19 June 1951” and other ad-hoc coalitions between EU member nations.

Far from the prying eyes of the European public, in the small town of Velsen in the Netherlands, in October 2007, the ministers of Foreign Affairs and of the Interiors of five EU nations signed the first treaty to establish a supranational and multinational military body of the European Union: the European Gendarmerie Force (EUROGENDFOR or EGF). The Treaty of Velsen was intended to form a “multinational police force with military status… which shall be operational, pre-organised, robust, and rapidly deployable, exclusively comprising elements of police forces with military status of the Parties, in order to perform all police tasks within the scope of crisis management operations.” EGF was founded as a complementary component, and under the direct auspices, of NATO and the UN peacekeeping forces. Indeed, the original treaty explicitly acknowledges considerations of “the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington on 4 April 1949… the Charter of the United Nations signed at San Francisco on 26 June 1945… [and] the Agreement between the Parties to the North Atlantic Treaty regarding the Status of their Forces, signed in London on 19 June 1951” and other ad-hoc coalitions between EU member nations.

The EGF is composed of over 3,000 militarized police from five founding member countries, plus Romania, which joined in December 2008. The contributing forces come from: Gendarmerie Nationale (France), Guarda Nacional Republicana (Portugal), Koninklijke Marechaussee (Netherlands), Arma dei Carabinieri (Italy), Jandarmeria Român (Romania) and the Guardia Civil (Spain). The EGF’s training and permanent headquarters are in Vicenza, Italy, but the force can be deployed among any EU member nations.

What Are the Implications?

The unification of the militarized police forces of several European countries has far-reaching implications for the balance of power between civil and military law enforcement and criminal investigations agencies. To understand these potential implications, one must consider the origins of such forces.

Militarized civil law-enforcement agencies are an almost exclusively European idiosyncrasy. These forces began, for the most part, as monarchic protection forces. In countries with monarchies, the forces are an integral part of the democratic expression and balance of power, as they represent a highly-trained specialized body that receives its orders through the military chain of command and is independent from the political class. As such, these forces are intended to protect the population from possibly oppressive political regimes. By contrast, civil law-enforcement agencies are meant to guarantee resistance to potential military takeovers of the civilian government.

In the case of Italy (my home nation) for example, the police force is fragmented into local police (municipal and provincial), forest guard, national police, financial guard (customs, immigration, smuggling etc.), penitential police, and the Carabinieri. Each of these have their domain of operation, and their decentralized nature is envisioned to prevent control of the entire civil law enforcement body by one individual. The Carabinieri are intended to ensure civil protection if the political class acts against the public interest or safety. Likewise, the other police forces are meant to protect the civilian population from possible military takeover, and to safeguard political and civil institutions.

The Carabinieri are considered to be one of the top policing forces of Europe. Together with the Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard), the Carabinieri investigate and arrest individuals for international and more complex crimes, such as human trafficking, Mafia-related cases (including the search for fugitive Mafia bosses), money laundering and drug trafficking. According to a statement by the Union of Carabinieri, their sterilization and incorporation into a supranational force is “a joke as believable as the Mayan [apocalyptic] prophecies, but it is true… the Arm of Carabinieri, in a future more or less distant, but certainly not remote, is destined to an inevitable disbandment… it is only a matter of political treaties.”

Theaters of Operations

The deployment of the EGF does not depend at all on the origin of the forces or the recipient nation. This is due to another international law, signed by EU nations in 2008, known as the Prüm Treaty. This document regulates access to police databases of neighboring countries for obvious security and criminal investigation purposes. However, since its establishment, the treaty has enlarged its scope and purview and established the legal foundation for the exchange of personnel and riot police equipment with the participating countries (Germany, Spain, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium). However, following its naturalization into EU law, the treaty allows for EGF to access virtually the entire EU territory (based on the Schengen agreement). This transnational nature is part of the mobility of the force itself. For example, the European Police Forces Training in 2009 (EUPFT 2009) was in Vicenza, Italy (home to EGF headquarters) and the EUPFT 2010 on anti-riot tactics was in Lehnin, Germany.

Not only can the national EGF forces be deployed to any country, even ones that are not signatory to the treaty, but also the civilian authorities of the receiving countries have no jurisdiction or oversight over EGF forces deployed on their territories. As Article 25 states, “The authorities of the Sending State shall have the right to exercise exclusive jurisdiction over military and civilian personnel where such civilian personnel are subject to the law governing all or any of the police forces with military status of the Sending State.” Imagine now, for example, that a member of the EGF kills an innocent person in a non-signatory nation: say, Greece. That member is immune from prosecution by the Greek state and must be dealt with according to the laws (and will) of the sending country. In addition, it is not the civilian authorities of the sending nation who oversee the criminal prosecution, but it must be internal to the EGF itself. As many of the bodies that make up the EGF act as the “military police” bodies in their respective nations, those who are meant to be policed are those doing the policing.

EGF have already been deployed in a variety of extra-territorial operations such as the disastrous UN Stabilization mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) which, according to diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks, were “poorly trained, spied on student groups, mismanaged and staged elections.” EGF have also been involved in the equally disastrous NATO training programs in Afghanistan, which have been investigated and denounced in-depth by activists, such as Pratap Chatterjee, and the EU peacekeeping mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is notable that all the areas of such stabilization and reconstruction efforts (by the EU, NATO and/or the UN Blue Helmet occupation force) are strategically advantageous, resource rich, and have a history of resistance against western imperialism and neo-liberal economic policies. Consequenly, these forces represent the military arm of western hegemony and of the global “empire” over which the UN Security Council presides.

Virtual Complete Immunity

There is a conclusive aspect to the Treaty of Velsen that must be mentioned because it is essential to the existence of the EGF and its immunity from civil or criminal prosecution. Article 21 of the Treaty of Velsen states “The authorities of the Parties may not enter the premises and buildings… without the prior consent of the EGF Commander, or where applicable, the EGF Force Commander.” In other words, no civil authority may investigate the premises of the EGF without their Commander’s approval, effectively removing the civilian oversight of the armed forces. Should barring of physical access to the EGF not be surprising enough, the same Article also states that not only the premises, but also “the archives of the EGF shall be inviolable… wherever they are located in the territory of the Parties” and makes no provision for the possible access to such archives by a court of law. Even if such provisions were made, Article 22 states that “the property and funds of the EGF and the goods which have been placed at its disposal for official purposes, wherever located and by whomsoever held, shall be immune from any executive measure in force in the territory of the Parties,” effectively barring any court from inspecting EGF’s financial records or property.

Numerous provisions, besides the aforementioned Article 25, ensure that EGF members will come under the exclusive jurisdiction of the sending state. For example, Article 29, Section 3 states that “EUROGENDFOR Personnel shall not be subject to any proceedings for the enforcement of any judgement given against him or her in the Host State or the Receiving State in a matter arising from the performance of his official duties.” Thus each EGF member benefits from complete immunity when deployed, when following orders (possibly illegal or immoral) or generally performing “official duties.”

The combination of these provisions — barring civilian access to premises, inviolability of archives, immunity from prosecution and investigation of funds and assets, and personal immunity for EGF personnel — effectively means that the EGF are unaccountable to any national civil authority and immune from prosecution.

Is this the kind of police force we want in Europe? Why was the European citizenry not consulted about police forces that will likely be used to squash popular dissent and maintain order by military means? What are the implications of becoming occupied by a non-emotionally and nationally invested police military force from another country? How can we allow such an institution to be exempt from scrutiny and prosecution by civilian bodies and courts? The EU was meant to be a union of the people by the people. Is it turning instead into a component of a global police state that uses structures like NATO and the so-called UN peacekeepers and EGF for repression?

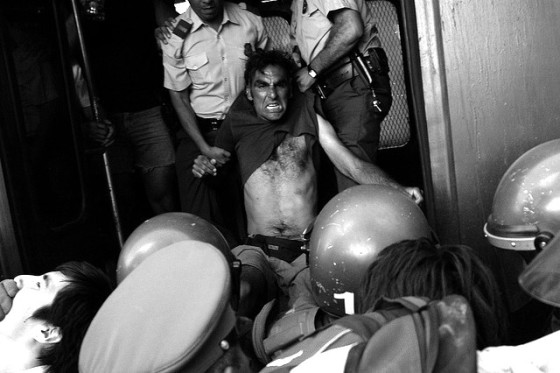

Editor’s Note: Ruben Rosenberg Colorni is a writer, fourth-year student of International Public Management at the Hague University, and an activist in a wide variety of causes ranging from the Palestinian occupation to environmental degradation. Although born in Italy, he has also lived in Indonesia, Thailand, the United States and the UK. Rosenberg Colorni currently lives in the Hague, the Netherlands, with his cat. Photographs one, three, five, seven, nine, eleven and thirteen by U.S. Army Europe Images. Photographs four, six, eight, ten, twelve and fourteen by Antitezo.

Related Articles

One Response to EGF: Europe’s Multinational Militarized Police

You must be logged in to post a comment Login