Magic Woman of Haiti’s Mountains

This is an excerpt from my upcoming book, Marabou of My Heart. Copyright © Dady Chery and News Junkie Post Press 2021. All rights reserved.

It is impossible to know precisely why, one week before my mother left Haiti, she took me to Croix-des-Prés and left me with Sò Gras.

If I had to describe Sò Gras’ milieu in a single word, it would be perfume. A giant Ylang-ylang tree shaded the last hundred feet or so of the dirt road that led to the turn toward her house. Every breeze along that stretch brought an immersion in a pool of perfume, because the tree had shed a thick carpet of fragrant petals as well as extended its horizontal branches, heavy with yellow flowers, low over the street. At the house itself, all day women waited their turn on the porch to file into the patchouli-scented inner sanctum for their herbal baths and consultations.

Sò Gras was as popular a manbo as my grandmother was a hair stylist. Most of her clients looked as if they had come for a business transaction. Some brought along their children. A few arrived alone, angry, confused, quiet and turned in on themselves, crying, or holding their faces in despair. These cases tended to take longer than usual, but Sò Gras’ skill was such that all her clients left with a straighter spine and sweeter scent.

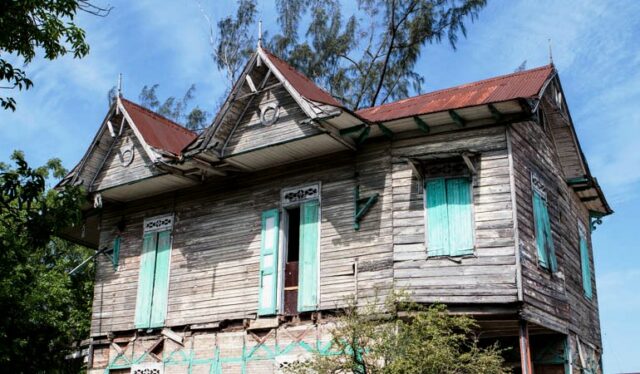

Beyond the porch, Sò Gras’ one-story house was divided into five rooms, all with cement flooring. The first was a large vestibule with a mirrored buffet, and a large straw rug on which stood a dining table surrounded by six wooden chairs with straw seats and backs. Colorful depictions of Haitian life decorated the walls. A hallway divided the rest of the house into left and right sections. The first two rooms had no door and directly faced each other. They were Sò Gras’ own room on the right, and the children’s room on the left. In Sò Gras’ room stood a large armoire, a stool, a mirrored vanity set with a crystal powder jar and family photos, and a surprisingly small bed for someone her size. By contrast, the children’s room was furnished with a bed so large that nothing else could fit in the space, and so high that we had to step onto a small bench to reach the mattress. All three of us slept on that bed.

We were not supposed to enter the two usually closed back rooms where Sò Gras took her clients, but we did, whenever we could hear her jingling charm bracelets recede toward the town center and street market. In the room on the right, green banana leaves usually lined the floor. Near the center, there were three chairs, a table with a brass incense bowl, and a tub half full of water on which floated fresh leaves of Wild Basil, Verbena, Soursop, or the blossoms of Sour Orange trees. A mortar two feet tall and pestle twice as long, sculpted from the wood of Sour Orange trees, stood in one corner.

In the other back room, on the left, everything was spare and immaculate. A table and two chairs faced an arched alcove lined with a silk drape. Depending on the day, the lustrous fabric seemed to change to red, blue, or green. On a bright-white embroidered linen cloth sat a framed image of a black Madonna and child, a heart-shaped red satin pillow about the size of a hand, silver necklaces, bottles of perfume, a goat skull, a cup of coffee or cocoa, and half-gourds with meal courses. The dishes were usually freshly cooked gryo, bannann peze, pistach grye, and diri kole ak pwa. My new friends said the food was for Èzili Dantò. I have since come to recognize her as the spirit from the Vodou pantheon who embodies love’s courage and fury. Èzili had not eaten at all. I proposed that this was because there was no sauce, but my friends insisted that this was how she liked her meals. Though the food smelled delicious, we did not touch it, because we calculated that the portions would be too easy to keep track of. We sprayed the perfumes onto our wrists, sniffed them, and then rushed to wash ourselves up to the elbows so we wouldn’t get caught stealing from a lwa.

A small door at the end of the hallway led to the kitchen and latrine in the house’s backyard. The level yard continued for a while before it descended abruptly into a mountain that overlooked Port-au-Prince and the sea beyond it. One had to be there to know that the mountainside was not merely verdant but also fragrant and lined by shrubs and herbs with crimson, orange, and yellow florets. I liked to sit quietly on a lichen-coated boulder to watch the afternoons unfold into sunsets over the bay. Anoles, larger lizards, and Hutias lived in the crevices; gorgeous Trogons and Palm-Tanagers visited the bushes. Free-ranging goats, chickens, guinea hens, dairy cows, and little black pigs passed nearby on their way home for the nights.

Near my rock, on a bed of moss one afternoon, I found a Haitian Emerald. From beak to tail, the hummingbird measured four inches, if one ignored the detail that its needle beak and tail feathers easily accounted for half of its length. My heart broke at the sight of that improbably tiny and beautiful bird, with one extended lavender wing that refused to budge even as its desire to take flight manifested in the glitter of its moving emerald throat in the sun. I cupped it in my hand to keep it warm and took it with me everywhere. Sò Gras learned my news and asked to see the bird, which I showed to her.

“A Wanganègès Mòn! These birds are really good for magic! I could use it!” she enthused. When it dies, give it to me, okay?”

The thought that the bird might die had not occurred to me. Tears welled up in my eyes, until I got an idea.

“If it dies, will you revive it with your magic?” I asked.

“I cannot promise you that, sweetie. All I’m saying is, just remember not to get rid of it, okay?”

“Okay,” I said, and wondered if this was an admission that her magic sometimes failed.

The bird refused my offerings of sugar water in a bottle cap. I hoped its wing would soon heal so it could go feed itself. That night, I emptied a large matchbox, bundled the small creature into a bed of moss, being careful to leave a narrow gap so it could breathe, and slipped the box under the bed. The moment I woke up, I checked on the bird. Its previously alert eyes were shut and its feet rigid. I left it there and went to my rock to cry. I walked back when I heard Sò Gras’ calls to come get her coffee and fresh rolls. At the breakfast, she informed us that she had taken the bird.

A huge ruckus from a Rara band on the porch startled me awake on my final night at Sò Gras’ house. Because of the stories I had heard from Denise about the skinless demons that roamed the night, whipping zombies and feasting on anyone they found, especially children, I was convinced I was about to be eaten alive. My friends laughed at me and ran expectantly to the front room. Sò Gras, who usually wore white, put on a red scarf and wide-skirted rainbow-colored dress. She lit all the kerosene lamps, walked to the front, lifted the door’s heavy black hook from its eye, and opened wide the entryway. Dozens of musicians and their followers poured into the open rooms of the house. “Onè,” they said, as they bowed to Sò Gras. “Respè,” she answered, with a wide grin. Some carried machetes. I rushed to my friends’ side for safety.

Members of the ensemble wore colorful sequined costumes that sparkled like hummingbirds as they moved. Its two leaders, a man and woman, sported the most elaborate sequin patterns; the man also wore a shiny hat from which streamed multicolored strips of cloth. Except for a large group of singers, the musicians came in sets of three. Three hollowed out bamboo tubes of different lengths preceded three metal horns that looked like long funnels, and three goatskin drums of different sizes. Each bamboo player also tapped on his instrument with a long stick. There followed a troop that rattled and beat smaller percussive instruments.

Sò Gras somehow found plenty of food and especially drink, which she always seemed to have. The visit turned into a huge party that burst with rolls of laughter while her guests ate and drank their fill, and she caught up on their news. When the libations were nearly finished, she squeezed some bills into the queen’s hand. The king gave a signal, the group filed out into the backyard, carrying the lamps, and the party began in earnest under a full moon. It was a complete show, and all the more extraordinary because it was unexpected. The songs usually began with a call and response between the male and female singers, or short riffs invented jointly by the different horns, which developed into polyphonic interlocked lines. As the drums and other percussive instruments kicked in with increasingly animating rhythms, the king and queen led the dances and juggle of batons and machetes. Rara, being an expression of service to a Vodou spirit, its bands did not stop everywhere, even if offered a contribution, but only at sites important to the lwa, like venerable old trees, graves of revered ancestors, or homes of respected manbos and oungans. I believe Sò Gras’s house was the group’s destination that night. They rejoiced in her dance and performed for us until the sky started to brighten. I hated to see them go.

I woke up to a strong scent of coffee in the vestibule. Sò Gras and my mother were at the table talking over a cup. I ran to kiss my mother and then disappeared into the yard for my morning toilette. I had learned to do this since I was about five. I filled a basin with about three gallons of water, dipped a small bar of soap into it, lathered up my face, neck and armpits, and then rinsed them from the basin. After this, I sat on the basin with my skirt extended all around it for modesty, to wash my privates in the same way, and finally I sat on a chair to do my feet. I dried myself with a towel, put on new panties, switched my old dress for a fresh one, and joined the breakfast table. When we were nearly finished with our bread and coffee, Sò Gras excused herself to the chamber with the tub and leaves.

She carried back a small crystal jar with a thin layer of gray power, which she put in front of me.

“Dady, this is from your little bird!” she said excitedly. “It is rare and priceless!”

My friends piped in that they had never before found this kind of bird or seen it from so close. In fact the bird’s Kreyòl name, Wanganègès Mòn, meant Mountain Woman’s Magic. Sò Gras explained that she had plucked the bird’s feathers, dried the carcass in the sun several days, ground it with her mortar and pestle, and then retrieved all that she could. Mom looked infinitely proud. Since she asked no further explanation, I assumed they had discussed the rest. I have since learned that a trace of Wanganègès powder is a well-known love charm. I believe Sò Gras had anticipated a singularly potent charm from my hummingbird, which was not trapped and killed, but rescued and loved.

Editor’s Notes: Dr. Dady Chery is the author of We Have Dared to Be Free. Photograph one by NH53; photographs two, seven, eight and ten by Jim McGlone; photograph three by United Nations Photo; photograph five by JayeshPati912; photographs nine, eleven, fourteen, and fifteen by Carsten ten Brink; and photograph sixteen by Likeaduck.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login