Mandela’s Legacy: South Africa Then and Now

“The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy of white supremacy.” – Nelson Mandela, Pretoria, April 20, 1964

States should rarely reflect, in their entirety, the bearing and views of their leader. States endure; leaders by their mortality do not, except in effigy or as memory. The passing of South Africa’s Nelson Mandela on December 5, 2103 will be met with fear and dread, even as the tributes flow in.

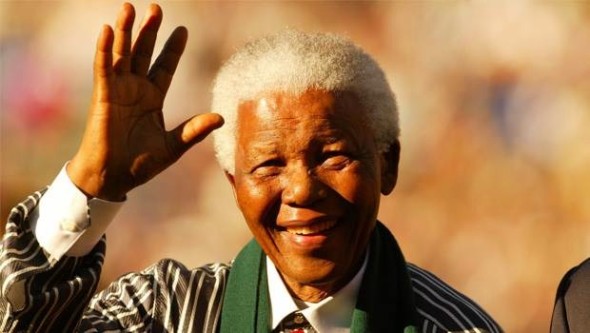

Mandela’s health and physical decline had been noted with fastidious detail. Medical check ups made the news as roaring headlines. “Mr. Mandela wanted a quiet exit, but the time he spent in a Pretoria hospital this summer was a clamor of quarreling family, hungry news media, spotlight-seeking politicians and a national outpouring of affection and loss.”

In June, Mandela’s eldest daughter Makaziwe would claim that those lingering outside the hospital were like “vultures waiting when a lion has devoured a buffalo, waiting there for the last carcasses. That’s the image we have, as a family.”

Like the scrolling account of the last days of the leaders of the Soviet Union, there seemed to be a greater foreboding lurking, the prospect of creeping calamity. Could South Africa survive in a post-Mandela world? Certainly, with figures such as South African President Jacob Zuma, hope will not be springing eternal.

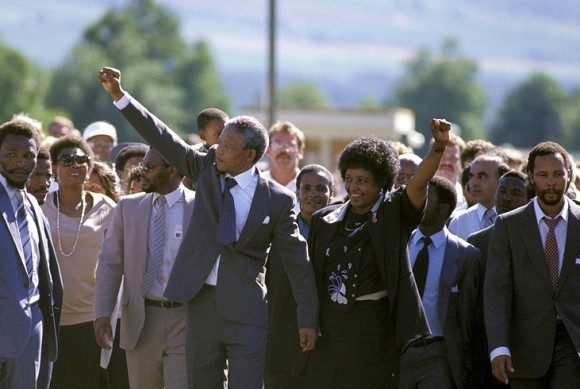

From the time of his imprisonment for treason as an activist in 1964, Mandela has made history. But it was only in 1980, when the African National Congress (ANC) decided to identify Mandela as the talismanic figure of the anti-apartheid movement, that he became a global figure of pop activism, the icon of racial liberation. The “Free Nelson Mandela” campaign was mobilized, and Mandela would muse about a misplaced celebrity. In South Africa, however, he was a feared opponent.

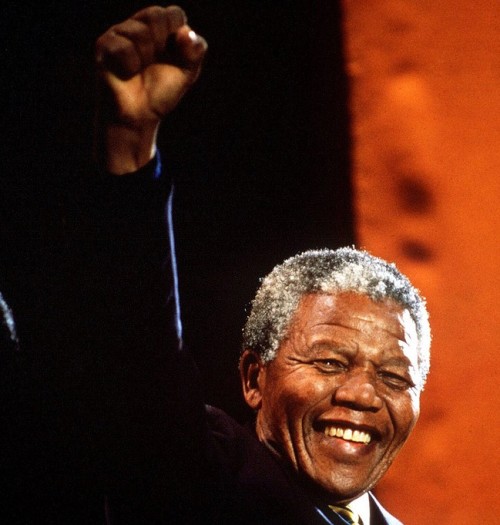

A few facets of revolutionary and political genius stood out in the Mandela psyche. One was a remarkable ability to avoid revenge as a tool of policy during his term as President between 1994 and 1999. He had much to be vengeful for – the personal reasons of incarceration, but more to the point, the imposition of one of the most sophisticated systems of social and legal control ever devised: apartheid.

Apartheid did not simply grow under the pens of fanatical theoreticians of race like the South African Prime Minister Daniel François Malan. Laws forbade integration between the races in the Cape Colony as early as 1685. As the explorer David Livingstone would note in 1850, “The great objection many of the Boers had and still have to English law is that it makes no distinction between black men and white.” Then came the patchwork mythologies of racial encounters – the supposed treachery of the Zulu leader Dingaan, who slaughtered the “peaceful” Voortrekker leader Piet Retief in what became the Weenen massacre of 1838.

The adoption of a vengeful approach would have made the creation of the Rainbow Nation, at least in principle, impossible. Mandela was no dogmatist or doctrinaire. Hatred, for him, clouded judgment and addled strategy. This was not to say that he did not flirt with pan-African nationalism or feel the stirrings of anger. “While I was not prepared to hurl the white man into the sea,” he observed in his autobiography, “I would have been perfectly happy if he climbed aboard his steamships and let the continent of his own volition.”

While Mandela initially embraced non-violence as a platform, he would put the ANC on the pathway of armed insurrection after the Sharpeville killings on March 21, 1960. With the militant musings of Che Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare, Mandela assumed control of the paramilitary Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). Then came the fateful association with the South African Communist Party, those Mandela claimed would “eat with us, talk with us, live with us.” At no point did this “Black Pimpernel” see any military combat. Firm ideals came hand in hand with a sense of pragmatism.

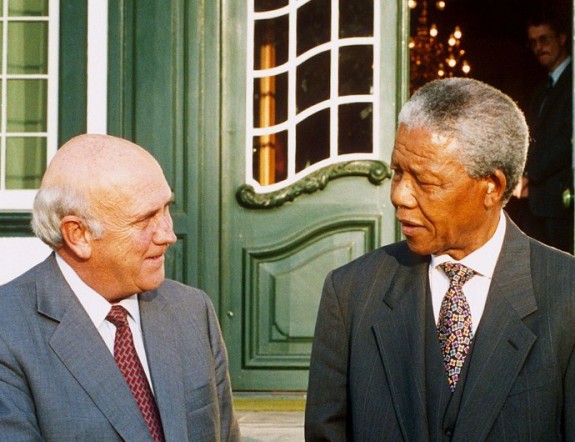

His shared Nobel Peace Prize with the last white South African President, F. W. de Klerk, was symptomatic of the project he pre-empted in the defense speech of his trial at the Supreme Court of South Africa on April 20, 1964. Violence had only been embraced after avenues of non-violence had been frustrated. Sabotage had not involved the infliction of a loss of life. The ultimate goal of his militancy was simple yet vastly ambitious: the creation of a non-racial state, and the removal of white supremacy.

Mandela was always wryly aware that history may well have taken a different route. The apartheid state was in a parlous state after losing one of its key pillars: the threat of the communist menace. An international-sanctions regime, despite various ingenious techniques of subversion by the Afrikaner government, had taken its toll. Wars against Angola and Mozambique at the end of the 1980s had proven ruinous.

The project of a racially unified, as opposed to divided, South Africa, proved to be a near impossibility. South Africa remains a country seared by conflict not merely between Whites, mixed races and the Black populations, but also between tribal Black groupings. Racial policy has become racial apoplexy, the contradiction and dysfunctional legacy of a country governed by the racial impulse. In a sense, apartheid was the bastard child of such division: a state, and a state of mind, forever obsessed with the racial imperative. For one race to survive, it had to repel and subjugate.

While in power, Mandela was accused of not being swift enough with reforms. Wealthy whites emigrated in fits of capital flight along with the feared brain drain. Cronyism became a feature of government. Much of the daily workings of governance were passed over to his ultimate successor Thabo Mbeki. Conflict between the ANC and the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party, led by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, proved vicious. Mandela eventually managed to contain a potential civil war – if barely.

Another aspect of the revolutionary genius of Mandela was not to linger in office like a faded romantic. There are few sights worse than a dusty old revolutionary in a hurry, and he proved adroit in handing over the reins before his second term had concluded. His role as an African and global statesman could commence.

Mandela’s South Africa continues to be plagued with racial issues. Since 2008, incidents involving attacks on foreigners have increased. In 2012, 140 lost their lives. Another 250 were wounded in what have been described as xenophobic incidents. Mandela’s South Africa remains complex and traumatized. As South African journalist Rian Malan described with poignancy in his memoir My Traitor’s Heart (2000), “Everyone had blood on their hands.” The singer Bernoldus Neimand’s words Malan chooses to quote are apt: “How do I live in this strange place?”

The ANC has become a shadow of its former self, a corrupt behemoth rather than a viable political project. It has been stripped by success and not moved beyond the prism of race. It has relied, with almost tedious regularity, on Mandela’s luster to conceal its mammoth failings. A state where race is defanged, rendered irrelevant in policy making, remains the greatest project Mandela bequeathed to his nation. It remains to be fulfilled.

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, three, four, five and six from South African Tourism. Photograph seven by Scott Rippon.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login