Oaks, Traditions and Conflicts: Serbia’s Unpredictable Stability

The bus from Novi Sad was proving impossible, an intemperate monster with narrow seating and dirty floors. Not an express, and certainly not this one, this bright red-tinted beast known as the Niš Express which runs through Serbia like a cholesterol-thickened artery. In Serbian, it might be better to term it the Nikad Express: one that is simply never an express, a permanently delayed mechanism of public transport. This is the humor that matters here, and to survive, it is indispensable.

The Serbian bus is a legend on wheels, a folkloric wonder that spices conversation and fills in the gaps of silences. Routes are unpredictable and chaotic. The drivers seem like otherworldly types, satanic servants who never disappoint in their element of surprise. Such dispositions were immortalized in the 1980 film Ko to tamo peva (Who is singing over there?), where a simple, even simpleton bus driver mans the wheel while his exploitative father sells the tickets in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia just prior to the German invasion of 1941. The final destination is Belgrade.

The crew is colorful and representative: amongst them a young, confused couple, a priest, a confidence trickster of a singer, people interested in order (yes, the Germanophile element), and an elderly villager. Of course, the Germans are around the corner with their jackboots and efficient principles. Exit one invader, be it the Turks, and enter the next. Serbia’s often haphazard sovereignty has tended to be an appendage of some other power.

Unlike our cinematic characters, the destination on this occasion, Orthodox Christmas, is rural southern Serbia, starting from the northern city of Novi Sad, which used to be an Austro-Hungarian bastion, a vestige of military opposition to Turkish challenges in the eighteenth century.

Bujanovac, Serbia

The southern town of Bujanovac, which only moved into Serbian hands before the First World War, has astonishing color, a dirtied, busy straddling packed with cultural mixes. It is jammed in a crushing vice: that of Macedonia, Kosovo and Serbia. Each place seems to be a stone’s throw from the town. All have been seen as illegitimate in history; all have challenged the orders, the agreements and the “understandings” placed upon them and each other. The thief’s code of conduct prevails, because the concept of survival has necessitated thieving to some degree.

Sultry Romani women trudge through the streets, their eyes ablaze with history and living. Locals with faces hewn by suffering – refugees from the Balkan wars, poverty and a sense of the desperate – populate the scene.

This region was the birthplace of the Serbian author, the Vranje-born Borisav Stankovic, who dramatized the rural world liberated from the Ottomans in 1877-8. But it was liberation merely in name, a cosmetic effect. The patriarchal flavors remained. Hierarchies retained power. His works suggest that history is inescapable, be it the patriarchy of custom, the beauty of the unchanging life. His dramatization of the Romani figure Koštana (1902) was not merely a work of moving literary greatness but idiomatic genius. The Gypsy lover, her indomitable presence, is the song of this earth. She is both victim and conqueror of the same society that seeks to imprison her. All passions are dangerous to order.

Albanians have a heavy presence on local council. They take the historical cue here and make their presence felt in Mercedes cars with Swiss number plates, though these four-wheeled creatures have a very local flavor. There is nothing of the corporate suit with them, though they are frightfully brash – they are about as Swiss as aromatic curry. But they know that the European Union will smile more on them than the Serbs, who are seen as the cartoon bandits of the next morality play. All talk about reconciliation in the region is based on direction rather than understanding: one group should behave so that the other prospers. This is mediation by the fist, though there are genuine conciliators at work.

Then comes the colorful, higgledy piggledy structures that dot the small town. Urban planners would find no employment here, given that there is no urban planning to speak of. The last must have left when the Turks evacuated in the upsurge of a decaying empire, paving the way for free will, an immolating Europe and a good deal of chaos. Inspirations behind the new buildings vary in their confused pursuits: vulgar Greco-Roman pillars, large tiled fronts (the more tiles, the more money, and hence, the louder the statement), Austrian mountain buildings reminiscent of Tyrol; neat, almost German ordered buildings, then pink anarchic structures that cry to be tidied.

The suggestion by Serbian locals is that the cars, the ostentatious though distasteful homes, the almost animation quality to the lifestyles, is a source of great problems. Skilful thieves in Switzerland can be admired kings in Serbia, though some of this is inspired by envy. It’s all a matter of degree and resourcefulness. Some of this relative wealth is entirely legal; social security in the Netherlands and Scandinavia is an abundant salary in itself. That money is brought back to Bujanovac, where it goes far. The locals who never leave speculate about their Romani counterparts. Do they belong? The commanding billboard leading into Bujanovac from the small village of Rakovac, hovering over a stream covered in rubbish, suggests that they do; the Romani permanent resident (yes, a seeming contradiction) are as entitled to have a green house, grow the famous peppers of the south called paprika, and state their claim to existence as anybody else. Funding for such projects has come from the European Union or the United States, depending on which guilty conscience, or which strategist has been involved. The views of local residents vary: such moves are either pure propaganda or the stuff of the best self-help manual one could imagine.

The vibrant, almost aggressively Albanian segment of the town is virile, growing in number, while the vulnerable Serbian center dwindles before the hearty yet deluding consumption of brandy called rakija, traditional rituals and depression of unemployment and low birth rates. The talk in Serbia is that of having children, and more children, fighting the demographic battle with other ethnic groups who seem to be gaining the upper hand in vulnerable areas. Demography is truly destiny here.

Since 2001, there have been cases of people trafficking, a thriving narcotics trade, and smuggling through the porous Serbian borders of the south. Both Albanians and Serbs are terrified: the Albanians at a heavy-handed response by security forces, the Serbs that the Albanians will outbreed them and initiate a rebellion in the manner of Kosovo. Locals have not forgotten the militant encounters between Serb security forces and the Albanian Liberation Army of Preševo, Medveda and Bujanovac, the latter keen to press the municipalities into Kosovo.

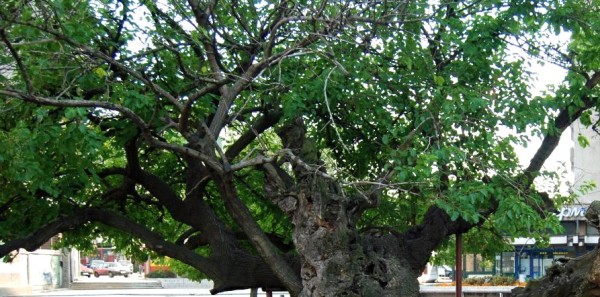

Demography comes with its traditions. The oak tree is sacred here. It is durable. It is strong. It has the pretensions of immortality. It might be burned in rich tribute during Christmas, but it will also support your hopes. There are no rooms for traditional conifers, those found in northern Europe. The oak tree is felled, be it by branch or trunk, with incantations muttered at the felling, and brought into homes as a welcome. Bunches are attached to cars. Bunches are placed in the boots of cars. There are dances around a bonfire with oak. A cauldron of rakija is boiled. Women and men meet, the women, as they always do, taking the insurmountable lead, the men limping behind with their liquid courage.

It can be argued that the motor of history, as ill-greased as it might be, is simply reasserting itself. The Ottomans made their own presence felt for four, seemingly interminable centuries, leaving their costumes, their timber homes, their public baths, pungent coffee and mores imprinted in the local DNA. The stunning traditional dress, the longing songs, the homes, the decrepit, dusky buildings in Bujanovac and the larger neighboring town of Vranje, remind one of Istanbul in miniature, the noisiness of Anatolia, the creakiness of custom. But the Ottoman pashas, with their authoritarian sophistication, are not Albanians, not princely rulers so much as wanting to make the steal and get the deal. Therein lies one of the problems of local perception. Be ruled, perhaps, but be ruled by worthy masters. As if to affirm the point, Turkish soap operas receive rave reviews, a form of continuing cultural imperialism.

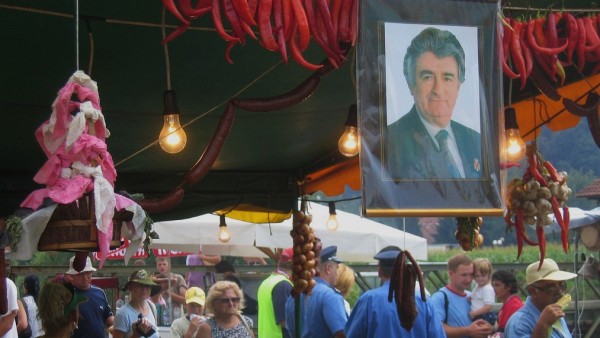

Seething away in cosmopolitan richness, trouble lurks in the region, as it has seemingly done for centuries. Rivalries between tribe and family always exist, but all it takes is an opportunist, a shot in anger, a bungling enterprise to get the attention of villagers and security personnel. Local posters, now very worn by the angry traffic and the soiling soot, remind citizens of Vojislav Šešelj of the Serbian Radical Party, now in The Hague facing war crimes trials.

There are calendars on sale of the monarchist and Chetnik leader Draža Mihailovic, who was betrayed by British ploys of misguided hope and accused of treason by Josip Broz Tito when Yugoslavia came into existence during the Second World War. The stretched television series Ravna Gora – where the Chetniks resolved to not merely fight the Germans but those against a greater Serbia – has given further impetus to an attempt to find another Serbia, the lost Serbia, the Serbia of sweet, luscious memories. Conflict peeks, and the situation, as described by military analyst Aleksandar Radic back in 2010, is “unpredictably stable.”

Such unpredictable stability is fed by the European Union, which featured in the news during the Orthodox Christmas. There is talk of reintroducing visas for Serbs traveling to the EU, though such inane chatter always peeks around this time. Brussels and Luxembourg are not merely different entities but different planetary creations, unkind Gods who operate with impunity. They have no meaning in Serbia, or for that matter much in Europe, except in the negative, dark forces who seek to dictate rather than converse. All conversation, in truth, is the prelude to a form of molestation, a sort of historical rape, one inflicted by policy diktat. They are the paper freaks, the regulation demons, the financial minders who dictate the rules and monitor the pulses of nation states. It is ironic, and more to the point absurd, that Greece now has the presidency of the very organization that has, to a large extent, deprived it of its sovereignty. Joining Europe has become the ultimate test, but it is a failed one. A united Europe might be the dream, but everywhere, bureaucrats are to be found.

The noose placed on Serbia is ill advised, though there never seem to be enough people stringing it together. Industries are only allowed to develop at a constipated pace, though much of this is self-induced. Naturally, such conditions breed further suspicion: Europe is out to get them like a vicious hangman, an encircling presence, a brute. The Croats can ban gay marriage by constitutional vote and worship war criminals as liberators, yet escape the rebuke of the European authorities. These are dark and dirty times, though the wise claim that this has always been the case. Local vandals and rogues are allowed to flourish in this poisonous climate, seeing a world that is nasty, brutish and all too short. The result is a mixture of cronyism, parasitism and vanishing funds. The EU might be advised to not participate in this, but the EU itself has been party to a crippling culture of financial hypocrisy.

In Bujanovac, the very act of living, with its unpredictability, is a matter of degree. One day an invasion, the next, a crop that might be reliable. Infrastructure is poor. Neglect is overwhelming. In Ko to tamo peva, the only survivors at the end of the raucous, chaotic bus journey are the swarthy singers. The Germans, through a bombing operation on Belgrade, have killed passengers and crew. But the singers shall keep singing. When all else fails, exercise the vocal chords and weep.

Editor’s Note: Photographs one and two by Novica Nakov. Photographs three, four, five and seven by Steffen Emrich. Photographs nine, ten and eleven by Christopher Robbins. Photographs eight, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen and eighteen by Dennis Jarvis.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login