Water for Profit: Haiti’s Thirsty Season

There is no shortage of water in Haiti. Yet, everywhere on the island, Haitians travel for miles to get water, pay dearly for it if they can find it, and sometimes die on their journey to collect it, like so many antelopes snatched by predators on their way to drink. How does a thing like that happen in a country that gets reliably drenched with more than 50 inches (130 cm) of naturally distilled rainwater per year? Haiti is blessed with two rainy seasons: April to May, and August to October, but even during the driest months of December to February, the country gets about 1.5 inches per month. The Artibonite River alone carries more than 26,000 gallons (100 cubic meters) of fresh water per second! Another 13,000 gallons per second flow through nine other rivers that crisscross the mountainous landscape. As if that were not enough, Haitians also sit on about 15 trillion gallons of groundwater.

The latest foreign occupiers of Haiti would like us to believe that they found the country in a state of wilderness, with Haitians defoliating the trees and bouncing between the bare branches like monkeys that had not yet discovered fire or the wheel. In reality, Haiti has had a system of pipes where communities could collect their drinking water since 1841. About 40 years after that, households began to be equipped with their own water, so that by the early 20th century, this group represented one third of the population. Haiti’s position with regard to potable water rivaled anywhere in the world and was contemporary with the construction of waterworks in cities of the United States. Keep in mind that it was in the mid-19th century that about 20,000 Londoners died of epidemics of Asian cholera. Their drinking water had become contaminated with the wastes of the upper classes, who had just become fond of water closets and did not care where their untreated wastes flowed. If this brings to mind the more recent contamination of Haiti by the United Nations “peacekeepers,” yes, plus cela change, plus c’est la même chose.

As in most places and for good reason, in Haiti the control of water distribution was the purview of cities. The Autonomous Metropolitan Drinking Water Authority (Centrale Autonome Métropolitaine d’Eau Potable, CAMEP) handled the water distribution in Port-au-Prince. Branches of the National Drinking Water Authority (Service National d’Eau Potable, SNEP) provided water in 28 other cities. Many of Haiti’s smaller communities and cities also built their own fountains and dug their own wells.

The average Haitian consumes very little water: about 10 gallons a day. By contrast, residents of most so-called developed countries consume 5 to 15 times more water, with the US being the most wasteful. This massive waste is directly linked to the advent of tap water inside of houses. According to the writer Ivan Illich, in the US, “wherever tap water reached the households, water consumption increased by a factor of between twenty and sixty, which meant that a rate of thirty to 100 gallons a day became typical.” Indeed, a major reason for the low consumption by Haitians is that almost no clean water is allowed to flow down a drain. Most Haitians, who are poor, collect their water in containers for drinking, cooking and washing. And even those who are more prosperous customarily lack water toilets or faucets inside their homes. The water is supplied to small outbuildings for cooking or showering and is used with a minimum of waste.

As Port-au-Prince’s population grew, the water authorities, as well as private concerns, added new branches to some of the water pipes. Tanker trucks also joined the delivery system. Thus the water system became privatized in a limited and chaotic way by the political class. According to a United Nations study, in 1976 the delivery of water to Port-au-Prince by CAMEP was about 17 million gallons per day, one half of which was wasted or redirected. This was certainly unfortunate for CAMEP, which was losing funds that might have been spent on its administration. On the other hand, Port-au-Prince’s population was less than 450,000, and even with the supposed waste or redirection, about 20 gallons of water were still supplied by the government per capita, per day.

Foreign aid and finance agencies like the US Agency for International Development (USAID), World Bank, and Inter American Development Bank (IDB) had gained a foothold in Haiti with the ascendance of the dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1971. As these agencies set about to drive small Haitian farmers into bankruptcy to create surplus labor for new sweatshops in the capital, they also financed a series of studies of the country. Superficially, these studies were meant to guide the eradication of poverty, but their real purpose was to provide information on how exacerbate poverty to its absolute limit and profit from it. One study in 2005, to identify the owners of Haiti’s water networks, was done by the Haitian branch of George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, which goes by the pretentious name, Foundation for Knowledge and Freedom (Fondasyon Konesans Ak Libète, FOKAL). This was an interesting detour for FOKAL, which appears to focus on cultural projects to catalyze the Americanization of Haitians. In 2006, the International Foundation of the Red Cross (IFRC) reported that 81 percent of Haitians lacked access to decent toilets, i.e. water closets. Consequently, the IFRC declared Haiti to be the world’s most unsanitary country and the only one that had become less sanitary in the previous decade. It did not matter that nearly all Haitians had access to latrines that were more sanitary than the water closets whose untreated wastes were dumped into bodies of water. The study also overlooked the heavy burden posed by the influx of more than 60,000 massively wasteful Westerners from non-governmental organizations (NGO), including the United Nations’ so-called peacekeepers, starting in 2004, and the Red Cross itself.

In general, the studies of Haiti’s water agreed that its population had outgrown its municipal water delivery systems, and this was true, especially in Port-au-Prince, where the population had reached 1.9 million by 2009 through a sustained and deliberate depopulation of the rural areas. It was nevertheless also true that there was ample water around for that population. New infrastructure would have to be built. The country could have dug more wells to expand its potable-water system and built water-treatment systems. Alternatively, or in combination, it could have widely adopted rainwater harvesting. This practice is common in regions like Central America and the Caribbean, with seasons of abundant rainfall, and it is especially well suited to countries like Haiti, whose mountainous terrain poses a great challenge to the installation of systems of water pipes. Furthermore, rain-catchment systems are inexpensive to install and maintain. None of these things were done. Instead, the government created the National Water and Sanitation Authority (Direction Nationale de l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement, DINEPA) in 2009 to control all the drinking water of the country.

Despite its socialist sounding name, there is nothing nationalistic about DINEPA. It is a foreign organization with a Haitian front: a director general who often reminds poor Haitians that DINEPA “carries out its mission around the implementation of investments, network development, sector regulation, and stakeholder control,” which is gobbledygook for centralization and privatization. The main stakeholders and financial backers of DINEPA are the World Bank, IDB, Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (Agencia Espanola de Cooperacion para el Desarrollo, AECID), US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Haiti’s contribution, through its Fund for Economic and Social Assistance (Fonds d’Assistance Economique et Sociale, FAES), is trivial compared to the others, as is its influence.

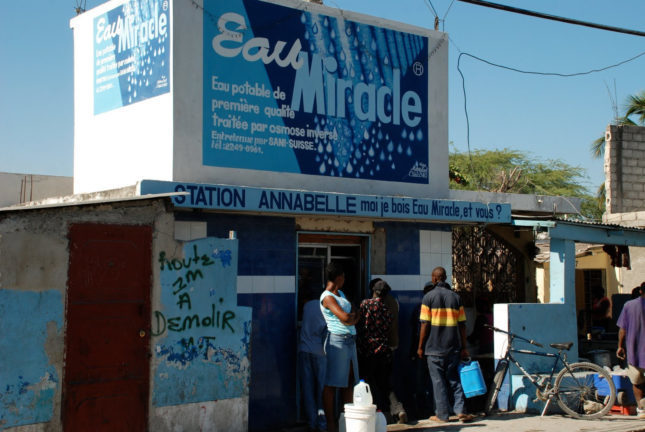

The main beneficiaries of these international funds have been the two largest water-privatization companies in the world: Veolia Environnement S.A. and Suez Environnement S.A., both multibillion-dollar French corporations. Veolia was initially contracted by DINEPA on April 1, 2010, less than three months after the earthquake in Port-au-Prince, supposedly to assist the humanitarian emergency there. After DINEPA contracted Suez in February 26, 2011 to rebuild Port-au-Prince’s water system, Veolia moved on to the other cities, where its operations expanded with the cholera epidemic of October 2010. By a strange coincidence, starting around 2011, throughout Haiti, potable-water systems have suffered a rash of sabotage and required reconstruction.

There is nothing remotely humanitarian about the privatization of water. The idea is pure evil and its practice should be a crime. It ablates the life savings of hard working people, displaces, and kills them. This plague does not stop in Haiti. It has already reached the poorer cities in rich countries like the US. In every case, the same forces combine to turn water into a commodity. Veolia and Suez, which are at the forefront of the project to privatize the world’s waters, have an impressive history of lawsuits. One of the more recent ones was Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette’s civil lawsuit against Veolia in December 2016. This lawsuit alleges that the company fraudulently submitted false and misleading statements to the public after its analysis of the water in Flint, Michigan. Contamination of this water with lead and other substances was associated with about 9,000 cases of lead poisoning in children younger than six, and an outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease that caused 12 deaths.

In subsequent parts of this series, I will dissect the mechanisms by which water is snatched from municipal authorities in places like Haiti and Flint, Michigan, and privatized. Find Part II here.

Editor’s Notes: Dady Chery is the author of We Have Dared to Be Free. Photograph one from United Nations Photo archive; two, three, five, six, and eight by Alex Proimos; four by Evamaria; and seven, nine and ten from the Pan American Health Organization archive.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login