COVID-19 in India: The Crisis as Seen from My Window

Ever since the lockdown began, friends have time and again asked me the same question. How am I managing my life in the lockdown? Well, for a writer like me, mid-afternoon solitude is nothing new. Solitude has become my second nature. Moreover writing and reading are essentially solitary affairs. Even in the past, I used to spend weeks and months quietly inside my room. I have spent countless days at my table from morning till dusk and seen from my window the sky change its color. I can do so without feeling the least compunction. If truth be told, I had quarantined myself a week before the national lockdown began with a shocking four-hour notice. What happened thereafter is all too well known. Business, schools, law courts, bazaars, public transportation: everything was shut.

On the very first afternoon every image that we saw on our TV corresponded to only one idea in my head: the doomsday. Our streets, alleys, thoroughfares even the by-lanes that once hustled and bustled with sound, sights, and smells of all kinds became silent. There was silence everywhere. An eerie kind of silence comparable only to the cemeteries I used to visit as a teenager. But as the silence descended, colorful animals took over our public spaces. It was a surreal scene from a painting or poet’s dream. Painful and spectacular at the same time, and it provoked in me a mixed response. Spectacular, because nothing is more beautiful than peacocks lazily walking our streets. Painful because it reminded me of the fact that presence of human beings is an impermanent affair: something that can be dispensed with. Perhaps this is how the earth will look like when there will be nothing left. Pink and empty.

As the silence intensified I dipped my soul into the books on my shelves. Living as I do under the commandment, Thou Shalt Know Everything, I forgot the daily cares of the world. I read with pleasure and at times in spite of exhaustion and boredom. In between these reading sessions I would text someone or watch the news with my father. In the initial days of the lockdown there were two sorts of news doing the rounds. One was of police atrocity. Indian police, as they have been depicted in novels such as The God of Small Things and countless films, are indeed cruel, professionally ineffective, and spectacularly violent. Shocking and disturbing images of the poor being beaten soon started to circulate on our TV screens. In the neighboring district of Howrah, a man died from a police beating when he went out to buy milk for his child. When things got out of control, the police did several PR stunt like singing lullabies in the neighborhoods of the rich.

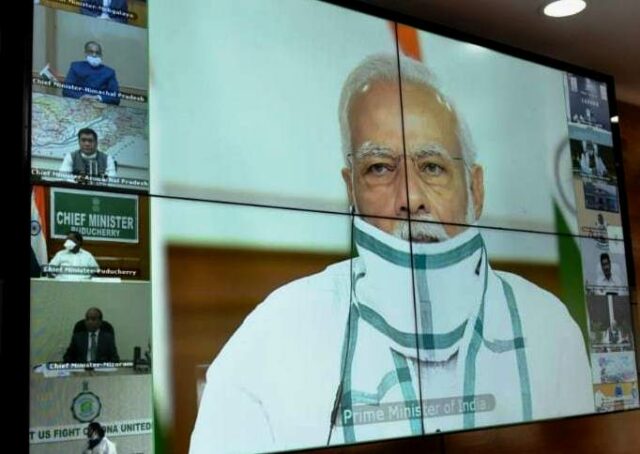

The other news that shook the ground beneath our feet was that of workers who had been forced to walk thousands of kilometers in scorching heat and dust to reach their homes. The sudden announcement of the government had not given them any time to prepare. Children born in the future, say in 2150 AD, may find it difficult to believe in such stories where ordinary human beings had to push themselves to what the French philosopher, Michel Foucault, called limit-experience. “How on earth can anyone walk from Delhi to Kolkata!” they might remark. Human will is indeed such a mysterious thing that, at times, it blurs the line between reality from magic. Netizens immediately started to compare the images of caravans of people walking on the highways with those of India’s partition in 1947. On TV it appeared that India had once again become a nation of nomads. Our generation has never seen anything as tragic and colossal as this. Soon thereafter the Prime Minister of India asked citizens to light candles to boost the morale of the health workers. This happened on April 5, 2020. I remember seeing, from my grilled window, yellow and red crackers bursting on the black firmament. This was proof of our love for symbolism. Social media was flooded with videos of people chanting, singing, and dancing rapturously to the tune of Go Corona, Go Corona… Go…. It was a bit depressing to see private neuroses acquire a universal character.

This crisis has once again revealed the tenuous structures of caste, class, race and gender that underlie our fragile social fabric. When news emerged in which members of Tablighi Jamat (Muslim missionaries) were blamed for spreading coronavirus, I was not in the least shocked. We humans have a tendency to blame everything bad, evil, scandalous, and criminal on those whom we have been tutored to perceive as our Other. This news brought back memories of a passage I had read and re-read from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment (1866, Constance Garnett translation). In the story, the young Raskolnikov is a theorist of crime. He ends up killing two sisters. He falls in love with Sonia, a prostitute, and is then impelled to confess his crime. Try as hard as he can, he cannot help but experience what medieval seers and poets have called a hole in the soul. His life is filled with a certain kind of anguish. I wish I had not done it…. Towards the end of the novel the narrator reports Raskolnikov’s dream.

“He dreamt that the whole world was condemned to a terrible new strange plague that had come to Europe from the depths of Asia. All were to be destroyed except a very few chosen. Some new sorts of microbes were attacking the bodies of men… Whole villages, whole towns and people went mad from infection.”

The narrator in Crime and Punishment blames Asia for spreading the deadly microbe, and thus reflects a widely held prejudice in 19th century Russia. Similarly, in Pakistan it was the Shia minority who were blamed for spreading the virus. In Southern China, it was people from the African continent who were perceived to be the exclusive carriers of the virus and debarred from entering the hotels and public restaurants. In the United States, pro-Trump white supremacist openly blamed Jews for the virus. Meanwhile, some Jewish and Muslim priests blamed the LGBT community. In India, middle class racists not satisfied with the blood of Indian Muslims went on the blame the Chinese and to urge fellow citizens to boycott Chinese goods. Anger was then vented on Communist Kerala – the first state to report and successfully contain the COVID-19 virus. Arabs too were not spared from this mudslinging. For days, calls for boycotting Muslim vendors did the rounds on social media. It was baffling to see vegetables and fruits acquire a religious identity. This was something that one had never encountered even in the hyper-realist plays and short stories of the great writer Sadat Hasan Manto. Corona jihad, the term coined by the Indian media to vilify the entire community would have shocked Manto.

It was only after big and small group of citizens reacted sharply and accused these people of spreading a communal virus that the narrative changed. Arab nations too took up this matter at the highest level, which helped things to calm down. And charging the discredited TV showman, Arnab Goswami, under various provisions of the Indian Penal Code that deal with promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, language or place of birth, also poured cold water on the issue. One summons by the police was all it required. In retrospect such behavior can be termed foolish, or perhaps dangerous. Conspiracy theories are not new to India. It is a country that abounds with such things. But it had never happened that the fake news manufactured by right-wing IT cells was contemporaneously amplified by the corporate media suits. The sheer scale of it was what made it horrifying. It could be said that in the history of human civilization it was by far the single biggest exercise in disseminating hateful news.

Another unfortunate phenomenon that has emerged from this crisis is this idea of charity. Suddenly we are told that private charity can undo a public catastrophe like the corona crisis. In India some states like the Left-ruled Kerala have done commendable work, thereby reducing the need for charity. It has done good groundwork by giving medical and financial aid to poor. It should help it stop the corona crisis and prevent a medical emergency from becoming a full-blown economic crisis. Maharashtra along with Delhi have done some work. But much of India, including West Bengal is lagging behind. Under the misguided notion of fiscal management, the state has left the vast majority of its citizens with no support system to rely on. Charity is filling this gap created by the state’s willful negligence. Such is the ineptitude of the political executive of the state that a vast majority of its citizens have been deprived of their right to life with dignity. Many have been forced to become beggars. The estimates suggest that about 100 million Indian workers could lose their jobs. Starvation deaths are already taking place, and thanks to a translucent system we may never know the exact figures.

It is time we realize that markets are an artificial creation meant only to serve the needs of a few to make a profit. As events have demonstrated, markets are insufficient, and blind reliance on them could lead us straight to genocide. Full employment, even in pro-market high school economics textbooks, is just an ideal condition. And automation will make it way more difficult for people to get jobs. Markets are more than happy to maintain a vast reservoir army of the unemployed. Apart from promoting competition among workers, thereby bringing down minimum wages, the markets stave off the risk of rebellion, unrest and insubordination. Markets have their limitations. And this crisis has more than any other demonstrated them. The worst outcome could be what lawyers call deterioration in the law and order situation. To what extend law and order would be affected by the worsening economic crisis is difficult to predict. But it is pretty common sense to suggest that there could be a link between the state’s failure to cope with an economic crisis and a steep rise in crimes like thieving, banditry, and maybe even murder. Crime in times of such distress is after all a coup from below.

At this juncture, the debates that flourished in the wake of 2008-12 economic meltdown have once again revived. The debate regarding market versus state responsibility will stay with us for now. As I write, interesting debates with high stakes are taking place on climate change, economic de-growth, eco-socialism, universal basic income, automation, and the role artificial intelligence (AI). We may waste this opportunity like we did with the 2008 crisis. Or we may just as well use this to give birth to a new generation of committed thinkers and citizens who place earth and people, not private profit and corporatism, at the core of their practice and theory. A crisis, or what we call internal dialectical contradiction, need not necessarily translate into social and political change. The crisis at its best provides us with surplus energy that has to be tapped. The crisis should be treated as a door that could lead us to either hell or a realist heaven. As we say, the future resembles a blank slate, and it is up to us to make whatever use we wish to make. The important point is that, this time around, we are condemned to choose.

Editor’s Notes: Imtiaz Akhtar is the author of Kafka Sutra.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login