Short Story Finalist: The Reader

Read only those books that inspire suicidal thoughts in you. Books, as I have always believed, are more dangerous than an atomic bomb. A bomb can only kill or maim you, unlike books, which alone can transform you. They can transform you from something baser into something nobler, something higher. A great book reveals you to yourself; it speaks to you about your sins and reminds you of your own faults. A great book is an event in your life. Its greatness lies in its ability to transform you. You willingly or unwillingly undergo a metamorphosis. What is a great book if not a mirror? This is how all that is baser is purged from you. One by one you lose them, you discard them, and you, sitting alone in your room, climb by inches the peaks of humanity. Reading is an escape from the world, but paradoxically one finds oneself embracing humanity in the most intense form known ever to the human race. A great book unsettles you, it uproots you as much as travel does. It provokes anxiety on a scale that is devastating. One experiences a mad tempest within. Day becomes a long hopeless evening. Dark clouds on the horizon that until yesterday meant little to you now portend your hasty end. Strange things begin to happen. Humans resemble mannequins and mannequins resemble humans. A great book kills a part of your being but, at the same time, it allows a newer being to emerge. The brown bud in you becomes a white rose. It reveals to you great secrets about language itself. By degrees, you realize that each word is like a living being with its own distinct skin beneath which it exists. How careful one has to be before one learns to play with it. Books are our collective memory. Without them we simply cease to exist. We become as terrifying as an abandoned bungalow.

Read only those books that inspire suicidal thoughts in you. Books, as I have always believed, are more dangerous than an atomic bomb. A bomb can only kill or maim you, unlike books, which alone can transform you. They can transform you from something baser into something nobler, something higher. A great book reveals you to yourself; it speaks to you about your sins and reminds you of your own faults. A great book is an event in your life. Its greatness lies in its ability to transform you. You willingly or unwillingly undergo a metamorphosis. What is a great book if not a mirror? This is how all that is baser is purged from you. One by one you lose them, you discard them, and you, sitting alone in your room, climb by inches the peaks of humanity. Reading is an escape from the world, but paradoxically one finds oneself embracing humanity in the most intense form known ever to the human race. A great book unsettles you, it uproots you as much as travel does. It provokes anxiety on a scale that is devastating. One experiences a mad tempest within. Day becomes a long hopeless evening. Dark clouds on the horizon that until yesterday meant little to you now portend your hasty end. Strange things begin to happen. Humans resemble mannequins and mannequins resemble humans. A great book kills a part of your being but, at the same time, it allows a newer being to emerge. The brown bud in you becomes a white rose. It reveals to you great secrets about language itself. By degrees, you realize that each word is like a living being with its own distinct skin beneath which it exists. How careful one has to be before one learns to play with it. Books are our collective memory. Without them we simply cease to exist. We become as terrifying as an abandoned bungalow.

It was in the month of October that he left India to work for a law firm in country xy. The moment the flight took off, he along with others were surrounded by a vast dark nothingness. Surrounded by death, he experienced a strange feeling of solidarity with his fellow passengers. Early morning, when his flight was about to land, he could see in the distance the sparkling blue waters of the ocean meet the bright sky. A yellow crescent-shaped circle of sand enclosed the water. The sheer beauty struck him. But he knew like all exiles that the sky and land did not belong to him. By now his eyes were hurting because of sleeplessness. He took his luggage and boarded a spacious bus. As the bus moved, he saw the lonely white-colored minaret of the mosque glow in the heat of the desert like silver. He saw restaurants with names like Delhi Durbar and Bangladeshi Hotel, which made him slightly happy. It was inside these air-conditioned hotels, he would learn later, that emigrant men would sit and watch with unblinking eyes, and sometimes with moist eyes, the news channels of their country. People even watched advertisements with a lively interest, he had observed.

For a while he closed his eyes. He could not remember when he fell asleep on his seat. When he opened his eyes, he saw yellow deserts on both sides. As if to confirm this, his eyes looked out of the driver’s frontal glass. He felt a sharp pain in his heart. It was as if he had a heart attack. A sharp pain rose from somewhere and struck his solitary heart. He realized that this was not his country. He felt an urge in him. He wanted to run stupidly and reach his home. He consoled himself that he had as a child suffered this feeling of homesickness, but this consolation added to the depth of his pain. As he entered a Pakistani restaurant to eat biryani, his eyes saw a huge framed poster of Jinnah wearing a shirwani and a gandhian cap made of fur. He quietly took his meal and left.

It was Friday, and he had not turned to the mosque. He had to leave his room quickly so that his colleagues, on finding this, would not interrogate him about his absence. He had decided to travel to a nearby mountainous region. The bus was nearly deserted. An American woman wearing jeans and a thick t-shirt sat on her seat with her legs crossed. A young Indian couple with a chubby child sat near her. When his eyes met the woman, she sympathetically smiled at him. It meant, “you too are from India. I know this, so are we.” The bus then left. From his wide windows, he could see tall buildings made up of mirror. Some were pointed as a sharp pencil. The facade of each building reflected the other. When he had seen this army of images for the first time, he thought it was Disney World, but the joy of this realization was short lived. His bus then had reached the fringe of the city. A blue board announced “labor camps,” which was written in white. Next to it was a desolate flat cemetery unlike those he had ever seen. Workers, as he learned later, lived there with poverty, solitude and bugs. Once in a while a group of workers would kill another fellow worker and then the whole gang would be mercilessly executed on Fridays. The next day the newspapers would carry a small story. Workers would invariably be blamed for having failed to pay the blood money.

His bus reached the mountainous region. The barren brown mountain stood below the clouds. Shafts of rays were falling on his body, piercing the dark clouds. Small platoons of workers could be seen breaking the mountain. The brown mountains with red sun above them evoked a feeling of longing in him. His mind pictured the smiling face of his M. He thought: there she is on the mountain top. He longed with such an intensity that, to calm his heart, he placed his forehead on the cool glass of the bus. Had someone touched him, he would have fallen on the ground and shattered like a glass. The bus gave such a sudden jerk that his mood disappeared. He tried hard to get back that mood, but he failed. The failure to experience anxiety in turn brought anxiety. Suddenly his eyes caught sight of a tree. A big tree. There it stood. Without leaves. Naked. Solitary. Its bark was light brown. Was it silently awaiting death, he thought. As he could make out, there were many bushes nearby. But the tree as it stood was aloof. Each branch was clear as the blue veins of a cotton-white hand. The tree reminded him about himself. In its essence he saw his own.

It was the 6th of December. The country was celebrating its independence day. School children marched with posters of the king and the crown prince. Huge posters of the king covered the facade of almost every building. A happy king smiled on his overtaxed subjects. In some buildings, flags long as a road covered the whole facade. One could see poor workers sell flags to small children on every street corner. Had Orwell or Tagore been alive, how they would have seen this great pantomime of nationalism, he asked himself. Freedom here is an abstraction performed in a poet’s restless head. He quietly jotted these words in some remote corner of his mind. As he sat on a wooden stool in a park, he saw spy cameras on top of the buildings in all four directions. They were seeing me, he knew this. Were they aware of his thoughts too? He left with a copy of My Name Is Red that he had been carrying. He walked towards the canal. Happy Europeans were busy in their abundant world. Some were sipping juice while others were munching chicken. A group of workers in dirty Kurta and Paijama were eyeing them.

The next day, after he came back from his work, his mind was blank as it had been yesterday and the day before. This made him ashamed of himself. An empty mind he thought, empty as the park he passed. He walked down hurriedly like a thief. He walked towards the public library. It is the only place where he could find peace. Here I am. It is here that I belong. My metaphysical palace. Here I am, amidst my ancestors who will now speak to me. How privileged he felt to belong to their company. Some day,when I die, I shall want to be buried here, amidst books. Books gave him solace. Here and there, a line would echo and re-echo within his soul, until it would die — suddenly having lost its charm. One of the greatest joys that comes from reading is that, time and again, one would feel that a philosopher, like Kierkegaard let’s say, suffered so much humiliation and pain at the hands of Corsiar, the Danish Church, the college Professors or his fellow Danes, that in the centuries later to come, when one would be born, one would read him. It was for me that he undertook so much of pain and labor. It was to instruct me in the future that he labored in the past. Hence, what can I feel for him, if not reverence and bonding? After having read for four hours, he came out of the library.

The crescent-shape moon just behind the yellow minaret of the beautifully lit mosque caught his attention. Dot-sized stars sparkled in the dark sky. He saw a group of tourists sitting on the top floor of a small ship. Somehow he could not identify with them. Reading had secreted solitude in him. The category of what philosophers call “the other” repelled him with such vehemence and force that he was quite ashamed to admit it before anyone. He walked slowly towards his room. He took the long way, a beautifully lit street that gets flooded with prostitutes every evening. Some stand with folded arms and melancholic eyes. Some give a smile calculated to lure young men with lonely hearts.

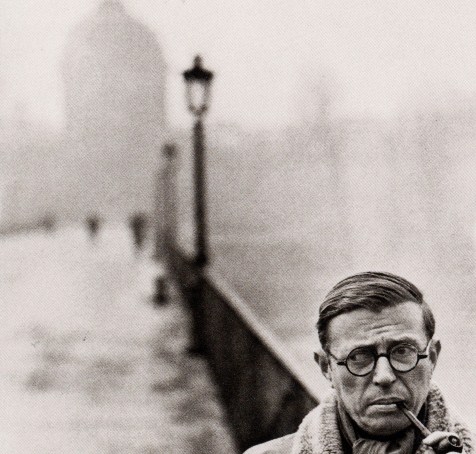

One Monday evening, he was reading Sartre’s Nausea. The confused Sartre was explaining his confusion with such clarity that it awed him. The sheer poetry of the text overwhelmed him. He knew that, sooner or later, he too would experience the nausea once he delved his heart into the text, or maybe he read the text because he too wanted to experience nausea. He thought Sartre had written the autobiography of his soul, but he also knew in some corner of his mind that it was a lie. After he had finished reading the text, he felt a strong urge to pleasure himself. He quietly went to the bathroom of the library and locked himself. To terrify his self, his mind played that old game, “what if someone catches me,” but a part of him knew that this anxiety enhanced the whole pleasure of the act. He washed his hands and quietly left the library. The same night, when he went to bed he had an anxiety dream. Next morning, when he met me at a cafe that was once frequented by M.F. Hussain, who would every evening come barefoot and order his paratha and omelette. his eyes were surveying the ships that carry goods. I knew he was looking for our ship Hind.

“Do you know,” he suddenly said, as he looked into my eyes with a conviction of one who is possessed with a truth, “that books can transform you? You end up being what you never were. You end up hating your parents. Your childhood friends no longer understand you. Your parents no longer understand you. You end up hating yourself. You get drunk and write that often I cannot endure my own self. And then, when you wake in the morning you feel embarrassed and also proud for having expressed it.”

I understood what he wanted to say. I expressed my comradeship by being silent for a while and, out of habit, I took a deep breath. I looked fleetingly into his eyes. I understood that he understood that I understood. After a while it started to rain. It was the first winter rain. We sat inside the empty restaurant. The light-yellow sands became dark. The pieces of newspapers lying here and there became translucent. Small rivers, like the roots of a tree, appeared everywhere on the sand. For the first time in months, I saw the wipers of cabs move. In the bus stop that faced our restaurant, a group of people stood helplessly. Men with long beards entered our restaurant. Tiny droplets of water were caught in their beards.

“It must be raining in our Calcutta too,” he said with a smile on his face. And we both smiled.

“You know, whenever it rains for more than 20 minutes in Calcutta, every street and narrow road becomes a tributary of Hooghly,” he said.

I smiled and added, “once I saw a poor worker sleeping under the rain with a blue plastic covering his body, while I was walking near the Burra Masjid area.”

When the streets are flooded in Calcutta, school children with white ribbons in their hairs are seen happily wading through the water. Old men sit and drink tea all day long in one of those dilapidated tea stalls, simultaneously cursing the government and god. I remembered having read an article by a certain journalist, which said “the cacophony of the politicians begins with the first droplets of rain in our city.”

When the rain halted abruptly we both came out. The air smelled of sweet earthen mud. The view of the canal was crystal clear. White birds appeared suddenly from nowhere. We could see the birds take swift glides towards the water’s surface to get hold of their prey, and from the water’s surface they would rise like kites. I so badly wanted to wet his lips with mine. I knew he too wanted to lick my lips. But I thought the kiss would offend him. And he thought the same thought at the same time.

“Listen,” he said, “will you come tomorrow evening at this place?”

“Why? Is there anything you want to talk about? You can do so now.”

“No, we will talk about it tomorrow.”

“Okay. Then see you tomorrow.”

We parted.

I opened my door, which creaked so distinctly. I then placed my key on my table and walked straight to my kitchen. I heard the drag of my footsteps. The refrigerator hummed loudly when I opened its door. I could hear the sound of the speeding cars that abruptly passed by my window. Slowly the sound would become faint and die. I opened my vodka and drank it. With each gulp my head became more violent. I was in such a state that I was unable to pursue any topic beyond a few seconds. A multitude of voices raged in my head. To feel tranquility, I got up and went to my balcony. I could see the full disk of white. The moon. On observing it, I realized that it was not a full moon, but a slight part of its base had eclipsed. When you look at the moon you look at your inner self, I thought. In the distant corner, a row of tall buildings stood hazily in the smog. A solitary lamppost burned dimly, like a smoldering ball of fire. Black crows appeared on the sky. Their shadows were flying. I gulped a few more glasses of vodka and went to bed. I saw in my dream that I was drinking water. I knew from my past experiences that it was a dream but could never halt the dream of my own accord and wake up. When I woke up in the middle of the night my throat was dry. I drank water and went to my bed again. I woke up in the morning and sat on my sofa with my book. It was as if every page that I read was forgotten before I could finish it. In my anger I threw my book on my sofa.

When I arrived at the cafeteria I found my cousin brother. He was speaking over the phone and smoking his cigarette. On seeing him, I was compelled to stretch my lips. We shook hands like diplomats.

“So what are you reading these days,” he asked.

“Nothing.”

“Why?” He exclaimed with a sarcastic smile evident on his face.

“I am equally happy at times when I don’t read. Besides, too much of reading gives you a severe headache.”

“Ha…haha… this is why I say. Stay like me, you will be happier.”

“Happiness without a cause is ephemeral,” I snapped back forcefully like a typical lawyer.

We sat silently for a long while. I did not feel any urge to speak. He had nothing to talk about, given his learning. He broke his silence after a while.

“The brotherhood has won the elections in Egypt. Soon they will spread their tentacles in the rest. Europe will become an Islamic continent. And so will India. These Christians have had their day. Their immorality will soon be wiped from the face of this earth by the swords of our warriors. All this I tell you is the sign of Doomsday. See the economic crisis, the poverty, the helplessness of our brothers and sisters. It is a curse of our god on these infidels. What do you say?”

“Your insanity is so patent, I need not say a word.”

“Why do you always take their side,” he asked in a disappointed tone.

“I cannot forgive the West for what they’ve done to our people in Vietnam, Iraq, Cuba, and Afghanistan, or any other poor country. But I cannot forget that they have given us Chaplin, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir. If the East has given them Algebra, they have given us laptops and phones,” I said.

Angrily I got up and left the place. Suddenly I remembered that I had forgotten about her. I went near the canal and sat. My one eye belongs to the East and the other belongs to the West. The immensity of the horizon enlarges when we look at it with both our eyes, I thought.

Fifteen years after a sudden absence, one day I received a letter. It was from him. He had settled in Darjeeling. He stayed alone in a rented room. For the greater part of the day, he would read. After quitting his job he had decided to live alone. It was during those days that I found him writing a book. It was titled “Poets and Governments.” He had explained to me on several occasions that governments of all political shades exploit the works of poets to maintain their discursive power. Repressive governments are poetically eloquent.

I remember the day I visited his solitary house. I had on purpose worn a red sweater. My big breast was swollen with pride. I knew that that night he was mine. We made love like wild animals. We swore to stand by each other for centuries to come. But by morning it was all over. I felt so ashamed of myself. He woke up and pressed his face to my breast. We stayed on the bed, coiled like worms for a long time.

He then said, “you know, I was so garrulous when I was alone. A part of my mind was always busy talking to someone.”

“Did you ever remember me,” I asked.

“Sometimes,” he said, looking vaguely at the ceiling.

He left the bed suddenly and went outside to buy a pack of cigarette. It was then that I found the page written by him that you read at the beginning.

Editor’s Notes: This story was a finalist in the News Junkie Post short-story competition. Photographs one, two, six and eight by Cory Doctorow; seven and nine by Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login