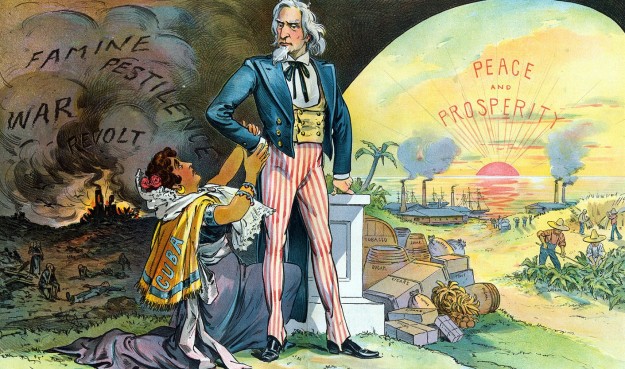

Imperial Monroe Doctrine in Force: Quiet Coups in Latin America, the Case of Ecuador

The appearance of stability in Latin America is preferable to any kind of political upheaval. The Monroe Doctrine is very much in force, but from a superficial look at elections and the constitutional order, one might surmise that the simultaneous United States-sponsored military regimes in Argentina, Brazil and Chile during the 1970s could not happen again. Overt dictatorships in Honduras and Paraguay are dismissed as being temporary anomalies. Yet curiously, the proverbial trains run on time, and the rate of growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) is approved by global financiers. A sudden respect for elections and increased trade with China are sometimes offered as the explanations for this apparent utopia. The stability of Latin America, however, is that of a comatose patient. It began with a massive peacetime expansion of police and military forces in Argentina, Brazil and Chile (ABC), starting around 2004, with sponsorship by the United Nations. Latin Americans were called up to crush Haitian resistance after the removal of Haiti’s democratically elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, by the country’s elite together with the US, France and Canada. South America’s military inclinations have reemerged from their dormancy. During the last decade, Latin American generals from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay have enthusiastically tested their weaponry and trained, expanded and modernized their armies in Haiti. These massive armies are beginning to chip at their home countries’ economies and civil liberties.

The 30-S coup in Ecuador

Through a continuous accretion as “peacekeepers” in the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), by Fall 2010 Ecuador’s police force had grown from about 10,000 to 52,000 troops; the military force had likewise grown to 72,644 soldiers. In a country of 15 million people, this amounted to one police or army troop for every 120 people. Being short of funds to finance this obese force, on September 29, 2010, the National Assembly passed a Public Service Law for all state employees that would cut the automatic salary raises that accompany promotions, extend the time between promotions, suppress bonuses and incentives, and put a cap on careers in public service involving mandatory retirement, among other things. The law was not vetoed by the President and was about to take effect on September 30, 2010: a day that has become known in Ecuador as 30-S.

More than four years later, various sectors of Ecuadorian society still grapple with 30-S. The President has vehemently called it a failed coup and assassination attempt. The opposition has said that there was never any coup intent and that the President had misrepresented a police riot to enhance his popularity. The local press has likewise concluded that evidence of a conspiracy could not be found, and 30-S was merely a police riot that had spun out of control. I wish to propose yet another explanation, which to my knowledge, has never been considered: a successful army coup took place in Ecuador on 30-S, but a powerless President was kept in office to give the appearance of stability.

On the morning of 30-S, three key places in Quito, Ecuador, were attacked: the country’s biggest airport, the Parliament building, and the headquarters of Regiment No. 1 of the National Police. At Mariscal Sucre International Airport, no flights could take off or land because a group of about 150 soldiers from the Air Force had closed the airport. At the Parliament, a group of masked policemen on motorcycles had blocked the lawmakers from entering the building for the morning session. Simultaneously, there was chaos in several other cities that were left unpoliced and where, in some cases, policemen started riots and set up roadblocks with burning tires.

At around 11 a.m. President Rafael Correa went to the headquarters of Regiment No. 1, where an angry group of masked policemen had demanded to speak to the authorities. After Correa, who had recently had knee surgery, was heckled and attacked with tear gas, he was removed by his escort detail to a police hospital adjacent to the barracks. The hospital was quickly surrounded by police rebels. Correa went to an upper-story window, removed his tie and opened his shirt to show that he was wearing no body armor, and he told the angry crowd: “kill me if you want, kill me if you have the nerve, instead of staying in the crowd, hiding like cowards….” At noon, the Presidency’s Legal Secretary, Alexis Mera, announced at a press conference in the Government Palace that a state of emergency had been declared throughout the national territory and that the internal and external security of the country had been turned over to the armed forces.

Negotiations

As part of the state of emergency, all private radio and television stations were ordered to broadcast the signal from the state channel for eight hours, in accordance with Ecuadorian law, and this resulted in a media blackout, especially regarding the chaos elsewhere in the country. Throughout this time Correa remained in the hospital, where the rebel policemen continued to control the perimeter. Attempts by the President’s supporters to approach the building were met with volleys of rubber bullets.

Between noon and 9 p.m. on 30-S, an intense series of negotiations took place between Rafael Correa, his Defense Minister Javier Ponce, who might have also been taken captive (but not in the hospital), representatives of the police rebels, and Ecuador’s military high command. Mr. Correa also communicated by phone during this time with numerous people, including various heads of state.

Despite the declaration of a state of emergency around noon, it took more than three hours for a message of army loyalty to the President to be broadcast by General Luis Ernesto Gonzalez, the Head of the Joint Command of the Armed Forces of Ecuador. That message was thought to have been recorded earlier but to have been delayed as a bargaining chip in the talks with the defense ministry. It took another six hours before an army operation involving 900 troops arrived to extract Correa from the hospital in a shootout. In all, the crisis left eight dead and 274 injured.

In the end, all money concessions were granted. In Ecuador, where the monthly minimum wage was $240 in 2010, the salaries of mid-range police and military officers were increased by 25 percent to between $400 to $570 per month. Salaries of army captains were raised from $1,600 to $2,140 per month, and the salary of a major was raised from $1,870 to $2,280 per month. Moreover, all the raises were made retroactive to January 2010.

Given the relatively weak positions of Mr. Correa and his Defense Minister during the negotiations, one might reasonably assume that the salary increases for the police and army were not their sole concession to Ecuador’s military brass.

Gutierrez family to the rescue

Throughout the crisis, Mr. Correa insisted that a coup was in progress and suggested that it had been organized by those who “cannot win at the ballot box.” After his rescue, he directly accused Ecuador’s former president, Lucio Gutierrez (2003-2005), a pro-US military man whom he had helped to unseat, of being behind the crisis. While Gutierrez denied that he ever had anything to do with the events of 30-S, he boasted that his daughter Karina, a lieutenant in the army, had participated in Correa’s rescue. In an e-mail to her father, Karina wrote: “Papito bello: As you know, my batallion is used in emergency situations. I went to the rescue yesterday, and I was in the middle of all the gas and shootings. I know that I would never risk the lives of our people. For this, I am proud of you. I love you.” Guitierrez’ brother Gilmar, a legislator of the pro-US Patriotic Society Party, further revealed that a cousin of the former president, Army Major Robert Vargas Borgua, had also participated in the rescue.

Contagious riots

In Bolivia, a police mutiny worse than that of 30-S took place in Summer 2012 that also required the army’s deployment. The crisis spread throughout the entire country, starting with a takeover of the headquarters of Bolivia’s riot police and eight other police stations. The government became paralyzed, and the riots escalated to bombings of the Parliament building and Presidential Palace, and breaking into the National Intelligence Directorate to destroy documents. Like Rafael Correa, President Evo Morales accused his political opponents of fomenting a coup. As in Ecuador, the crisis ended with an agreement that probably conceded much more than money to the army and police.

Stability of the comatose

Since the 30-S crisis, Ecuador has become second to none in its alacrity to support a dictatorship in Haiti. Ecuador was the very first country to renew its UN “peacekeeping” troops in Haiti after the dissolution of the country’s parliament on January 12, 2015. Since 2012, Ecuador has given military training to groups of men handpicked by Michel Martelly so as to create his new army of Tontons Macoutes. The training continues today, and this new paramilitary force is expected to be deployed in Summer 2015.

As recently as 2005, Ecuador was vituperatively called “the most unstable country in the western hemisphere,” because it seemed unable to keep a president in office for more than two years. After eight different presidents between 1995 and 2005, Rafael Correa was elected in 2006, reelected in 2009 under a much acclaimed 2008 Constitution, and elected yet again in 2013. Since 30-S, however, the Ecuadorian government has worked to undermine the 2008 Constitution by promoting a series of unpopular measures. The country has declared war on indigenous activists opposed to mining projects. A new judicial council has appointed and dismissed hundreds of judges. The National Assembly is set to amend the Constitution to allow, among other things, participation of the armed forces in public security operations and unlimited re-election of the President.

Editor’s Notes: Photographs two and nine from the archive of US Department of State; three and five by Andre Gustavo Stumpf ; four, six and eleven from the archive of Presidencia de la Republica del Ecuador; eight by El Freddy; ten and thirteen by Felipe Canova; and twelve by Senor Codo.

For more from Dady Chery about Latin America’s conduct as a Praetorian Guard for the US in the repression of Haiti, read We Have Dared to be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation, available as an Amazon paperback and e-book from Kindle and other vendors.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login