Humanitarian Imperialism: Aid as a Trojan Horse

We lived sustainably, with color and panache

Long before the word sustainable became fashionable, before Scott and Helen Nearing experimented with non-establishment living in the 1930s and concluded that their project had failed because it lacked community, before even Henry David Thoreau noted that “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone,” there was Haiti.

Haiti was not always aided. Between 1963 to 1972, for example, the country enjoyed an economic renaissance as it buzzed with the activities of small entrepreneurs. The Kennedy administration had cut off all aid to Haiti in 1963 so as to bring Francois Duvalier to heel. The short doctor with heavy-rimmed glasses, whom the world called Papa Doc, turned out to be a rather complicated dictator: keenly intolerant of dissent but fiercely nationalistic. He had come to prominence in Haiti as a leader of the 1940s’ negritude (black pride) movement that succeeded the United States occupation. He was nobody’s boy and afraid of no one.

Haiti thrived with style and panache during this decade that merely continued its earlier isolation as the world’s first black republic. A community that was sustainable, tolerant, and harmonious with its gods had been forged, with none of the starkness associated with sustainability projects. Haiti brimmed with laughter, flavor, music, and color. Things dear to the Haitian soul were valued: things that could not be bought. Anacaona’s descendants lived there, and their life’s purpose was self realization and the creation of art. This was the Haiti in which I grew up.

Some lyrics from a traditional song

|

A country of small entrepreneurs

In the Haiti of the 1960s and 70s, everything a poor Haitian ate, touched, or wore was Haitian made. I was poor, but I lacked for nothing. My family of 10 was supported mostly by one woman who, for the most part, traded her skills as a beautician for the skills of other small entrepreneurs. For the rest, she used the local currency: the Haitian gourde.

Local, organic, fresh, and in season

Every day my family breakfasted and dined on freshly baked bread and drinks of fruit juice, cocoa, or coffee. We lunched on large helpings of rice or corn, pulses, and vegetables, plus a little bit of meat. The meat was usually a cut of goat or pig. Fish, shellfish, or crustaceans were eaten when in season. Some Sundays, we cooked a chicken. Our meat consumption was so modest that one bird sufficed for a family of 10. All the food was local, organically grown, and fresh. All the animals were wild-caught or free range. All the vegetables were offered in season. It had been so for 150 years. We simply called it food.

As poor folk, my family could not afford an imported frigidaire. We had no use for a refrigerator because our food was brought to us daily by the marchandes: women vendors who strolled through Port-au-Prince’s streets with baskets of provision on their heads. Their walk was living grace, their dresses and scarves a riot of color. Every day, Auntie would call on the same women as they swayed past our two-room apartment in a gingerbread house. Auntie would bargain with these marchandes for their live chickens, milk, rice, flour, corn, plantain, fruits, and other edible goods.

“Ti chérie [little darling], tell me how much you want for three cups of this rice,” she would ask, for example. The marchande would propose a price. Auntie would describe her week and financial situation before offering a lower price. The marchande would in turn describe her own week to justify a higher price. After some discussion in which every sentence on each side would begin with “ti chérie,” the two women would agree on a final price and wish each other well, having learned a great deal more about each other’s lives than was necessary for their transaction.

Back then, the Haitian population was 80 percent agricultural, and Haiti produced 100 percent of its food. The first supermarket opened in Port-au-Prince a few months before I turned six. The fluorescent lights and reflective linoleum floors were dizzying, the fruits improbable. For that birthday, I dearly wished for one of the shiny red apples, and my mother saved up and bought one. I never let on that the taste of wax had failed to live up to the promise of the gleaming red fruit.

Custom-made clothes and shoes

Like every female in my family, I owned one every-day dress and one special-occasion dress. Those of us who went to school also owned two sets of uniforms so that one could be washed while the other was worn. All were sewn by my mother’s former schoolmate Paula. Mom would walk with me to Paula’s house, where we would pick a style from a fashion catalog, and Paula would measure and remeasure my shoulders, torso, arms, waist, hips, and legs. Mom and I would then walk to town to buy the fabric and deliver it to Paula. When Paula was finished with the dress, I would be summoned to her place for a fitting. Again, she would measure and remeasure… nip here, tuck there. A day or two later, I would collect a superbly tailored dress.

Likewise, when one of my two pairs of shoes began to wear, Auntie would walk with me to town, and together we would visit tens of small buildings, each one with its shoemaker. Auntie would bargain with each man before choosing the best deal. Each of my feet would be considered and measured. We would decide on the details of the heel, the sole, and the style of the shoe. A week later, I would return to walk a few steps in them, wait for the inevitable adjustments, and then take home my tailor-made brand-new shoes.

Clean water

Potable water that could be drunk without boiling was piped through the city of Port-au-Prince. As a rule, plumbing was excluded from the main buildings. Water faucets were found outside or in small shower buildings built of cement. Our use of water was necessarily economical, since the water had to be collected from a faucet and carried to our quarters for our cooking and washing.

Latrines

Water was not wasted in indoor toilets. We used latrines, which were placed well away from the main house above a hole many feet deep. When the hole became more than half full, a new one was dug, and the dirt from the excavation was tossed into the old latrine. The latrines were kept clean. Cholera was unknown in Haiti.

Schools

Although a fair number of lycées (high schools) and professional schools were state run and free, few poor Haitians were literate, largely because all the elementary schools were private. A minority of parents managed to save up for their children’s schooling by fattening a creole pig or some other means. I was among them.

By the time I was 13, I had received a typical Haitian education in history, geography, algebra, grammar, literature (mostly French and Haitian), Latin, Greek, and English. All of it was done by Haitian teachers. I had also received a series of vaccinations, all from Haitian doctors and nurses. I studied under a mango tree during the day and by the light of a kerosene lamp at evening. The lamp was Haitian made. The straw-seat chair that I leaned against the tree was Haitian made. All my textbooks were printed in town. The rest of our furniture was home made. I had watched an uncle shape, shave, and sand all of it. Some of this furniture was made of mahogany.

The marchandes, shoemakers, teachers, and Paula, were poor, like us. To our great bemusement, Haiti was called “the poorest country in the western hemisphere” even back then, because the economic activities of this informal sector were not computed in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In fact, Haiti was the richest country in the western hemisphere because it had the lightest footprint. Those who want to know about sustainable living would do well to learn about Haiti.

Haitian hunger is a natural result of aid policy

Haitian proverb: “Kaka poul pa ze.” | “What issues from chicken is not always an egg.”

International aid began to arrive in Haiti with the 1972 inauguration of Jean-Claude Duvalier as president, one year after the death of his father Francois Duvalier. The aid came from the United States government (USAID), the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank, and it required that Haiti’s economy be changed from a sustainable domestically-oriented economy into an export-led economy, to benefit the US. The motivations for foreign aid to Haiti remain the same today.

The following two items were noted as the comparative advantages of Haiti to be exploited as it was brought into a capitalistic world economy: [1]

-

Fertile lands and climate appropriate to year-round cultivation.

-

Low-cost, hard working labor force.

The aid agencies provided funds to wealthy Haitian landowners on condition that they switch large tracts of Haitian land from production of foods for the domestic market to the production of fruits and vegetables for the US market. Because the US market was nearby, the foods could be sold fresh there while in season; alternatively, they would be processed for export. Based on growth of GDP, the aid policies would look like a roaring success.

The expected consequences for Haitians are elaborated in numerous USAID and World Bank reports. Briefly, famine would ensue for Haitian peasant farmers and they would be displaced in huge numbers from the rural areas to the urban centers.

When the rate of urbanization proved slower than predicted, the Haitian creole pig was wiped out as part of a $23 million eradication and restocking program. This was the first major blow to the peasant subsistence economy, for which this pig had traditionally served as a savings account.

Another blow came with flooding of the Haitian market with cheap Arkansas rice during the Clinton years.

Yet a more recent blow came with the UN-introduced cholera epidemic that caused a large migration from the most fertile region of the country: the Artibonite River valley. Currently, less than 20 percent of the food for Haitian consumption is produced locally; as recently as 1986, this was 80 percent.[2]

Since the late 1980s, Haiti has known real hunger. Garment-factory wages have hardly budged from their inflation-adjusted 14 cents per hour of the 1980s. Corporations and their owners have paid no taxes.

Government-steered non-governmental organizations

The advent of NGOs in Haiti began with a large influx of funds to subvert the democratic process between the expulsion of Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986 and the election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1990. During this period, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) funneled over $2.3 million into Haiti. According to USAID’s own estimates, by 1988 US funds reached at least one third of the 1,200 or so NGOs in the country. The number of NGOs reached 16,000 (one NGO per 560 Haitians) immediately after the earthquake.

As the association between USAID and the NGOs has solidified, the hunger has intensified. Since 1990, for example, those US NGOs that accept aid from USAID have been allowed to cover their expenses by selling non-emergency food aid in Haiti’s markets, in a policy called monetization.[2] The food is generally of poor quality and foreign to Haitians. For example, this has included unfortified Arkansas rice that caused scurvy in prisoners.

If Haiti has become poor, let us be clear on the fact that it was not always so.

Yes, the earthquake has hurt Haiti, but capitalism has hurt it more.

Long ago USAID predicted that, if successful, its aid policies would cause famished farmers to migrate from the Haitian countryside into urban areas, and this would in turn cause the population of Port-au-Prince to double to 1.6 million by the 21st century.[3]

The population swelled as predicted. Then the earth beneath Port-au-Prince shook.

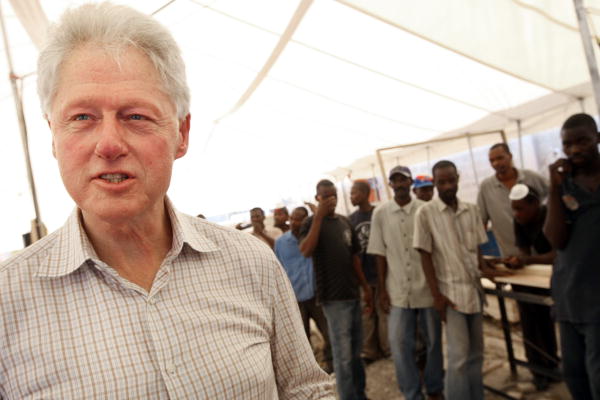

Editor’s Notes: Photographs one, four, five, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen and sixteen by Alex Proimos; photograph two by Sky Slicer; photographs three, six, fifteen, eighteen and twenty by United Nations Photo; and photograph fourteen by David D.

-

The Haiti Files: Decoding the Crisis, James Ridgeway, Editor. Essential Books, Washington D.C., 1994.

-

Sak Vid Pa Kanpe: The Impact of U.S. Food Aid on Human Rights in Haiti. New York School of Law Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Partners in Health, RFK Center for Justice & Human Rights, Zanmi Lasante, 2010. By 2010, Haiti’s domestic food production had plummeted to a mere 40%, and Port-au-Prince’s population had tripled to over two million from its 1981 number of about 800,000.

-

USGS. Earthquake Information for 2010. The earthquake of January 12, 2010 killed about 316,000 people, injured 300,000, and created over one million homeless. Calculation by Dady Chery: considering that more than two thirds of Port-au-Prince’s population came there as a result of foreign-aid policy, this implies that USAID, the World Bank, and IDB are responsible for over: 211,000 Haitian earthquake deaths; 200,000 injuries; and 670,000 cases of homelessness. There has been no word about reparation, only talk of more foreign aid.

For more from Dady Chery on Haitian history and the effects of foreign aid on Haiti, read We Have Dared to be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation, available as a paperback from Amazon and e-book from Kindle and other vendors.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login