Glitter of Brazil’s World Cup Hides Inequality, Corruption, Human Rights Abuses

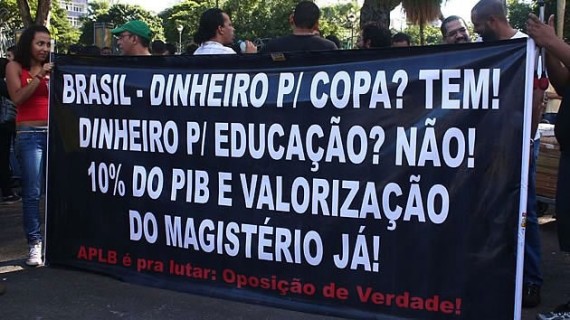

International financial and neoliberal institutions, most notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have created conditions in Brazil that led millions to protest throughout the country. Images of the protests bring to mind photographs of the 1968 hundred-thousand march against the military dictatorships.

How did it start?

It began with a demonstration at the Confederation Cup: an odd and rather recent tradition of organizing a mock World Cup in the host nation one year prior to the actual event. This is intended to evaluate the progress of the host country’s preparations. The demonstrations began earlier than most imagine, and their neglect by the mainstream and alternative media begs the question: How could we have ignored such a momentous event?

Despite the enormous foreign and domestic investments poured into the modernization of Sao Paulo for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, not everyone has been able to find a place on board the steamrolling train to “progress.” The discontent, although largely ignored, has been expressed throughout the decade that characterized Brazil’s ascension to a letter in BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China): an acronym synonymous with growth, emerging markets nations and superpowers. Most of the discontent relates to the fact that the sixth or seventh largest economy on the planet, by nominal GDP, has as yet been unable to address the fundamental fact that it also ranks with the bottom 15 nations for income equality and distribution.

A rise in the cost of public transportation sparked the spontaneous protests. This price hike followed a series of incidents that revealed a less-than-transparent connection between the state authorities and the companies that control the urban transport network: a relationship that led Brazil’s “Court of Audits” to condemn the fact that the quality of service had deteriorated despite increasing state transfers to these companies. Simultaneously workers’ salaries remained frozen, and the position of ticketmaster was eliminated and added to drivers’ duties.

The cumulative tension exploded into demonstrations that have widened in scope to denounce a variety of socio-economic problems. The protests grew from 230,000 people on June 17, 2013 and, fueled by widespread police violence and mass arrests, swelled to nearly two million by June 20. Subsequently, they moved from city to city.

Corruption and clientelism

In Brazil, corruption and clientelism are widespread: more so than one might expect from a country that has been praised in mainstream financial circles for the transparency of foreign direct investments and that claims to have raised the standard of living for millions of its citizens. The culture of corruption has its roots in neoliberal puppet governments supported by the US since the 1964 military coup against João Goulart, but the governments of Presidents Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff have also been marred by scandals. Last year, for example, over 24 Lula-government officials were convicted of participating in a “mensalao” cash-for-votes scheme that almost brought down the government in 2005 when the scandal initially came to light. Despite the guilty verdicts, many are yet to be incarcerated due to a lengthy appeal process, marred by delays, that has justifiably enraged Brazilians. Rousseff’s administration has also witnessed the expulsion of almost 10 ministers for allegations or charges of malfeasance and corruption, despite her assurances that combating corruption is “state policy.” To add insult to injury, a law is under discussion that would curb the investigative powers of the federal judiciary police and magistrature, coincidentally, in cases of money laundering and corruption.

Continuous corruption has marked the rule of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT – Worker’s Party) that brought Lula and Rousseff to power, but corruption is not the only factor that has eroded the PT’s support from many who had unquestioningly supported it: there is also the evident disparity between the anti-globalization, anti-imperialist and populist rhetoric extolled by PT’s leaders and the opposing neoliberal policies they have enacted.

Fictitious growth

Brazil’s economy is considered to be one of the most promising and rapidly growing in the world. The root cause of the ongoing socio-economic crisis is not a simple mismanagement of resources, but rather a consequence of the neoliberal macroeconomic agenda pursued by the PT’s predecessors, and continued by Lula and Rousseff. Lula’s election in 2002 symbolized the hope of a dispossessed nation and embodied an overwhelming vote against globalization and former President Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s pursuit of a pervasive neoliberal economic model and policy framework. These were perceived by Brazilians as a US imposition that had caused mass poverty and unemployment throughout Latin America. Many Brazilians became immensely disappointed by Lula’s failure to deliver on his promises and his adoption of the economic model he had condemned.

As one of Lula’s first tasks, he appointed Henrique de Campos Meirelles to head Brazil’s Central Bank (Banco Central do Brazil). Meirelles had been the president and CEO of one of the US’ largest financial institutions (7th then) and Brazil’s second-largest creditor institution (as of 2003): Boston Fleet, previously known as BankBoston. Boston Fleet was one of the main financial institutions involved in the speculative exchange-rate machinations against the Brazilian Real in 1998 and 1999. These were estimated to have made a 4,500 percent profit on an initial $100 million investment, for a total of $4.5 billion. The “Plano Real” caused a speculative bubble that initially ensured a supply of cheap imported products and forced domestic producers to sell their goods at lower prices to maintain their market shares; this plan culminated with the January 1999 Brazilian Currency Crisis. Meirelles was eventually charged with Tax Evasion in 2005 but denied any wrongdoing and maintained his post until 2010.

The Bank of Brazil (Banco do Brasil – BB, rather than the Central Bank) was put in the charge of Cassio Casseb Lima, who had worked for Citigroup’s operations in Brazil and begun his career under Meirelles’ tutelage in BankBoston in 1976. In other words, the head of BB was personally and professionally linked to two of Brazil’s largest commercial creditors: Citigroup and Boston Fleet. “The new PT team in the Central Bank is a carbon copy of that appointed by (outgoing) President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The outgoing Central Bank president Arminio Fraga was a former employee of Quantum Fund (New York), which is owned by Wall Street financier George Soros,” wrote Luis Miranda.

Thus Brazil’s financial and monetary policies were owned and managed not only by Wall Street executives, but also by individuals with a direct interest in further indebting the country while exploiting its resources to repay existing debts. Unsurprisingly, IMF Managing Director Horst Köhler praised Lula’s actions at a December 2003 press conference: “I am assured and I am quite confident that President Lula and Brazil, the political system, will do their own job and I am confident this will pay off.”

The job is indeed paying off! The total cost of the 2014 World Cup has already surpassed $30 billion, and the infrastructure for the subsequent Olympic games will require another $14.4 billion: a budget “just a touch higher than the combined budgets for the three other finalists.” It could be argued that South Africa got a GDP boost of 0.5 to 0.7 percent from hosting the previous World Cup, and Brazil might get similar results, but who will benefit from this increase? The ice-cream vendor on the beach might make a lot of money for a week, but will the event improve his life? Far from it. Indeed, for many people it could be quite the opposite.

The multinational, corporate, profit-driven infrastructure projects related to the World Cup and Olympic Games are wrought with corruption. They have resulted in a massive gentrification that has displaced hundreds of people and further indebted the country to foreign creditors. This is a common outcome of mega-events that also took place during the preparations for the London 2012 Olympics. The gentrification-driven destruction of Brazil’s favelas is far broader than in England, and reports of this phenomenon have circulated for two years, yet no particular notice has been taken.

Human rights

In Brazil, neoliberal policies have resulted not only in a huge rise (31 percent) of homeless and unemployed in urban centers in the last couple of years but also in a disregard for indigenous rights, especially a continuation of the exploitation of indigenous tribes and their lands to benefit the domestic and multinational corporations that are industrializing the Amazon. As part of the gentrification of Rio de Janeiro, for example, the Aldeia Maracanã center of Historical Native Culture was forcibly evicted so as to be transformed into the museum of the Olympic Committee. Citizens, and especially the Native Indian community, were excluded from the bidding process for the building and any say in its future administration.

Confidence has also faltered about the government’s ability to deal adequately and transparently with domestic human rights abuses. Pastor Marco Feliciano, who has been appointed to head the Parliamentary Commission for Human Rights, is reputed for defining homosexuals as “persons to be cured” and opposing abortion even subsequent to a rape. He is considered by many Brazilians to be unqualified for his position: an opinion that has instigated heated disputes in the parliament and is shared by human rights organizations.

Given this compendium of factors, it is hardly surprising that Brazilians are rising up. The nationwide protests are supported by 75 percent of the population. Angry Brazilians from the poor favelas and middle-class alike are chanting: “If your children get sick, take them to a stadium!” and “The giant awoke!” The promise of a “New Brazil,” free from Western-imposed neoliberal economic development, delivered exactly the policies it was supposed to discard. Brazilians have been betrayed by the PT’s charming mask of progressive rhetoric. The mask is quickly falling away to reveal the true face of Brazil’s “democracy.”

Editor’s Notes: Ruben Rosenberg Colorni is a writer, fourth-year student of International Public Management at The Hague University, and an activist in a wide variety of causes ranging from the Palestinian occupation to environmental degradation. Although born in Italy, he has also lived in Indonesia, Thailand, the United States, the United Kingdom and currently lives in The Hague, the Netherlands, with his cat. All photographs by Semilla Luz.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login