A Tale of Two Concentration Camps: Guantanamo and Ruhleben

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness… it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair…” With such oxymoronic sentiment begins one of Charles Dickens’ great classics from which the title of this article is derived. Dickens knew a lot about prison life, since his father was in the Marshalsea debtors’ prison. The eponymous “Little Dorrit” was born in prison, and it is widely held that her father, William, also known as “The Father of the Marshalsea” was based on Dickens’ own father.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness… it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair…” With such oxymoronic sentiment begins one of Charles Dickens’ great classics from which the title of this article is derived. Dickens knew a lot about prison life, since his father was in the Marshalsea debtors’ prison. The eponymous “Little Dorrit” was born in prison, and it is widely held that her father, William, also known as “The Father of the Marshalsea” was based on Dickens’ own father.

In diverse ways, the last 100 years have been a century of degeneration and decline. The 1914-18 war was described as “the war to end all wars,” and observers of history might be forgiven for looking on this quotation with a certain degree of cynicism or skepticism. What is difficult to contest, however, is how prisoners of war were treated so much better 100 years ago than they are today, in what we like to think of as a progressive age of enlightenment in which the belief in freedom and democracy is sacrosanct and an ideal portrayed as being of paramount importance.

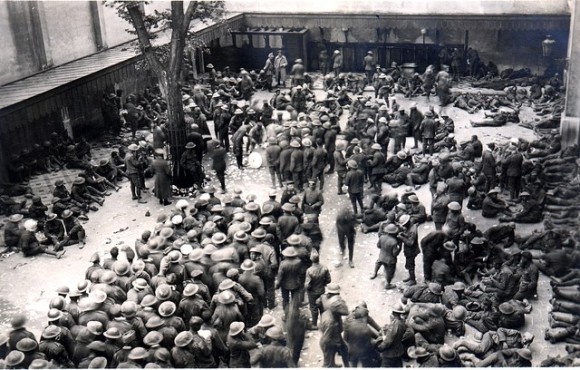

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base is a contested strip of coastal land in Cuba that the United States has seen as being its own property for many years. Its legal right to be there is not the purpose of this discussion, but one fact is quite clear: there is nothing in international law and nothing in any treaty, contested or otherwise, that legitimizes a prison camp where foreigners can be held without charge, or without trial. In times of war and conflict, nation states do tend to set up prisoner-of-war camps, and anybody not native born may be herded with others into a communal facility where they can be monitored in case any of them turns out to be “an enemy of the state.” This was the basis for the camp at Ruhleben on the outskirts of Berlin. Ruhleben prisoner-of-war camp was a converted race course manned by sentries. It had much in common with Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp in that it was established at the beginning of a war and contained foreign nationals without trial and without evidence of any criminal activity.

Unlike Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, in Ruhleben Camp there were joint activities, and it was a thriving community with social functions, sport and intellectual pursuits. Amid the despair of incarceration, there was hope. There was even the hope of escape, as there would also be in the Second World War. Today all hope of any decent life, any hope of escape, has disappeared with high-technology monitoring and security systems. What is even worse is that because torture is a feature of modern western prisoner-of-war institutions, those who have been tortured, even though it is known that they are innocent, and even though they have been cleared for release for six years, are not released. Such is the case of Shaker Aamer. Shaker is a victim of one of the most heinous miscarriages of justice ever.

In Ruhleben, when prisoners were cleared for release, they were released. For one example, take a look at the case of Alex Boss and George Hackenschmidt. At the start of the First World War Boss had a shop on Unter den Linden in Berlin selling specialized English goods of leather and silver items and other high-end products. Hackenschmidt, a wealthy man in his own right, was a former world champion wrestler who had only been defeated twice in his entire career. Unfortunately for him he had joined Boss in Berlin. Alex Boss had actually been the master of ceremonies who presented Hackenschmidt to the public early in the wrestler’s professional show-business career. Both men ended up in Ruhleben, just because of where they happened to be when one country declared war on another.

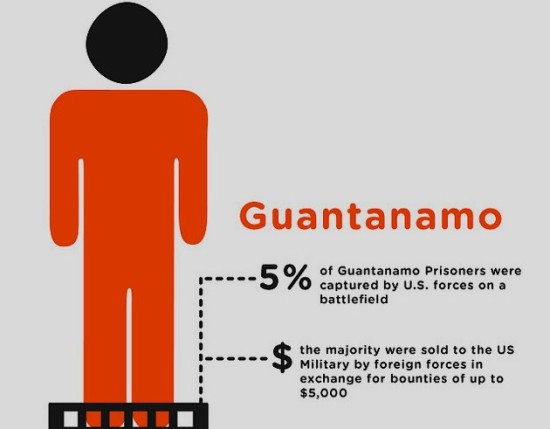

Similarly Shaker Aamer has been and still is imprisoned in Guantanamo because the so-called “war on terror” was declared by George W. Bush, and Shaker happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Shaker (pronounced Shacker) and Moazzam Begg were sold to the US for $5,000 each. They had gone to Afghanistan to open a charity school for boys and girls. The school, and their homes, were bombed to oblivion by the Americans when they began their never-ending war in Afghanistan in 2001. As ever, the bounty hunters, even in the 21st century, appear to have been the winners in how the modern west is governed, selling innocent men to the Pentagon sheriffs in a country where gun-slinging cowboys rule. Obama promised to close Guantanamo and return its prisoners to their homeland. Instead he is teetering on declaring war in Syria to replenish his concentration camp with a new intake of supposed enemies of the US.

Moazzam Begg’s father campaigned for the release of his son, even appealing at a school in Bordesley, Birmingham, in 2003. Moazzam was released due to this campaign but his friend Shaker was not so fortunate. Shaker has an eleven-year-old son in London he has never seen, and he is not the only man in Guantanamo who has a child he has never seen, let alone never held. According to Ahmed Errachidi, they call Shaker “The Professor” in Guantanamo, which presumably has much to do with his extensive knowledge. He was a translator for a firm of solicitors. The US, that once great country, is keeping an innocent man interned in a facility that has been likened to Hell. Shaker is a sick man, being force-fed by a new band of torturers. He was cleared for release in 2006, and it is widely held that the reason he has not been released is because of previous torture that the US seeks to keep the lid on. God bless America.

Alex Boss fought a mock-election campaign in Ruhleben. Voting was based on the English electoral system and Boss stood as a Conservative candidate in 1915. That same year he was released from Ruhleben. The prisoners in Germany 100 years ago were treated much better than US prisoners of war today. They had their own printing press and published a regular magazine called “In Ruhleben Camp.” This magazine is a testament to conditions inside the camp. One issue even had a front cover in color, and it sold for threepence (thrippence) instead of the usual twopence (tuppence). Is there an equivalent magazine in Guantanamo? If there is a magazine, it is for those running the camp. Shaker Aamer only last month was refused a copy of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago probably because he would be able to make comparisons that would be unfavorable to Guantanamo.

“Five paces by four and a half, five paces by four and a half, five paces by four and a half.” Whether it is the fictional Charles Darnay pacing out the size of his cell in the Bastille 250 years ago, or the fictional Amy Dorrit’s father in the Marshalsea, 150 years ago, both were treated better under the law than internees at Guantanamo, because each had been tried and found guilty of a crime. Ruhleben 100 years ago was a virtual holiday camp in comparison with that evil monstrosity built on a contested strip of coastline in Cuba. It is the shame of a crumbling empire when no compassion is shown to prisoners.

Editor’s Note: Photographs one, two, four and seven of POW of World War I from the archive of Drake Goodman. Photograph three by US Navy; photograph five by US Marine 0311; photograph six by Amnesty Inter. Australia; photograph eight by Steve Rhodes; and photograph nine by Geek Stats.

Related Articles

4 Responses to A Tale of Two Concentration Camps: Guantanamo and Ruhleben

You must be logged in to post a comment Login