Cameron Goes to China: Morality Takes a Back Seat to Business

They turned up as an entourage from a distant land, seeking to pay their respects to the emperor of the orient. What British Prime Minister David Cameron’s large mission to China, heavy with business leaders and political offering, suggested was that little has changed in the chess pieces of tribute in international relations. Imperial power, actual or nascent, demands respect. The small, even those of power past, will cower, and the small who wish to make peace and money will go out of their way to please.

There was much in the manner of diplomatic puffery on display, the icing on a cake, where the cake is conspicuously absent. Terms such as “mutual respect and understanding” were traded between the Cameron delegation and Beijing, but there is very little in the manner of such respect. The Chinese had kept the British on ice since Cameron met the Dalai Lama in London in May 2012. It was time to crack open the champagne, if only a modest vintage. Investments were being promised.

The Chinese Global Post smelt something odd in the clothing of the British delegation. “His visit this time can hardly be the end of the conflict between China and the UK.” It then had a good sharp stab at the British Prime Minister. “The Cameron administration should acknowledge that the UK is not a big power in the eyes of the Chinese. It is just an old European country apt for travel and study.” Truly, an oriental burden had emerged: Britain, formerly an empire, is now merely a tourist destination and university machine.

At Shanghai University, Cameron decided to have his own dig at the Chinese leadership, hoping to scrape some ground on his giant counterparts. He professed to having answered unscripted questions at a question-and-answer session, a monumental feat in that sea of oriental despotism. “There are two good things about prime minister’s questions. The first is that it puts the PM on their [sic] mettle, it puts them to the test… The public can see you are on your mettle, they can see you’re doing OK.” Then, the spurious suggestion that such questions made “the government accountable. It means the whole mass of the government has to account for what it does through one person, the prime minister.”

Cameron had, of course, answered scripted questions, showing the true worth of the great British democracy he represents. If it isn’t written and vetted before hand, don’t answer it. Chinese politburo members can take heart that their great challenger is, at the end of the day, a public relations poseur in charge of a closed-circuit television state.

The Chinese have certainly had their eye on Cameron and a declining United Kingdom for some time. “It is interesting to note at what point in history a nation appears to recognize and subsequently confront the moral decay of its societal fabric,” observed the editorial staff of The China Post in the aftermath of the riots that affected Britain at the time. For those at the paper, Cameron was particularly taken with moral issues, those which had seen the corrosion of British society. Like an antiquated conservative relic, Cameron was speaking of “laziness, irresponsibility and selfishness,” meddling in the role of parenting, and speaking about “what is right and what is wrong.” Cameron’s compass, as students of his behavior should have noticed, is distinctly confused.

On this high-profile trip to China, Cameron was particularly interested in the financial aspect. Morality was to take a back seat – at least at stages. “There has been criticism from the British media that I am putting too much priority on the economy and business on my visit. But I’m pretty unapologetic. Britain is a trading nation… it is very important we trade more, we invest more.”

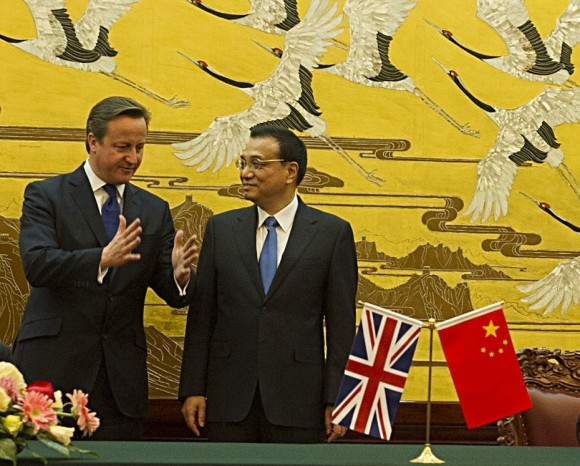

The moves have been considerable. Cameron has issued an open invitation for Chinese investment in the High Speed 2 rail line from London to, as papers call it generically, “the north” of Britain. (British rail projects rarely worry about destinations outside London.) Chinese Premier Li Keqiang obliged, telling those at a press conference in Beijing on Monday December 2, 2013 that he was interested in plowing Chinese investment in the £50 billion ($82 million) scheme. “The two sides have agreed to push for a breakthrough and progress in cooperation in the areas of nuclear power and high speed railway.”

There are certainly incentives for the Chinese drive to sink their investing fingers in the rather dingy pie that is modern Britain. Beijing would like a solid base in the financial center of London. Britain’s infrastructure creaks and moans, craving investment, though it is unclear what share will be taxpayer-funded and what will be a hand from external sources. The money will be welcome, though the extent of it should be troubling to British electors. Money may not smell, but it has the air of authority. The Chinese wallet, with its heavy contents, has been announced with much fanfare. The British government salivates at the prospect.

Editor’s Note: All photographs from the Prime Minister’s Office.

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment Login